“Both [Rino] and [Pierina] grew up in a time when the war caused challenges and poverty for their families. However, they had many stories from their childhoods—usually using humour to get through the hardships. Their experiences gave them the courage to make their way in a new country. While they both had traditional upbringings, they were both working, hands-on parents. They missed their families dearly, but they also learned that they could ‘never go back’, especially after visiting Italy years afterwards. They never lost their love for the beauty and more sociable lifestyle that they left behind.” – Ornella

Table of Contents

Introduction

In order to form a full and complex picture of my grandparents’ lives through the traces that are left of them, I am choosing to critically engage with several concepts that may affect the outcome of my project. This process is ongoing, as I analyze different theories of memory, understand experiences of Italian-Canadian immigrants and interpret oral family history, photographs and historical documents as my archival sources. Photographs will make up the main body of content for this project. Other items, such as postcards, newspaper articles, bocce trophies and certificates, will supplement the photos. As I analyze and categorize the photographs, it is important for me to be self-reflective. The photographs represent layers of historical, social and personal meaning that affect how I choose to articulate the narratives of my grandparents’ lives.

First of all, I will take into account the forces that led my grandparents to migrate. Due to the economic depression, damaged infrastructure and legacy of fascism caused by World War II, Italians faced widespread unemployment and poverty (Iacovetta 6-8). With few job opportunities available in Italy, my nonno was drawn to Toronto, a city that was not ravished from the war and was experiencing a post-war economic boom that required workers to support its progress (Iacovetta xxii). My nonno, like thousands of other Italian migrants, had planned on returning to Italy to live there permanently with the money he earned from his years of work in Canada. My nonna, on the other hand, may have been more dependent on her husband’s decisions. As both Iacovetta (77-78) and Cancian (71) assert, the experience of migration is gendered, and my nonna’s journey to Canada was not exempt from this. After marrying her fiancé who was ten years older, my nonna lived with my nonno’s family for six months before migrating to Canada herself. As Cancian points out, many Italian-Canadian women held secure jobs during the 1950s and 1960s, however, they were still primarily valued for their domestic and reproductive abilities (77). While my nonna adhered to social norms, such as patrilocal residence before immigrating to Canada, her new home also offered new freedoms and kinships with other working immigrant women (Cancian 78). Following her husband to Canada also enabled my nonna to improve her socio-economic status, as her family had suffered from poverty in Italy.

While historical writings and studies allow me to understand the facts and shared experiences that characterized many Italian immigrants’ lives, the subjects of my research are not mere objects of statistical analysis nor strangers. As Brah states, the experience of diaspora cannot be painted with one brush; in other words, it is not a homogenous narrative (208). One of the most blatant issues that I must call attention to while pursuing this project is the fact that I am the descendent of the people I am studying. Because I am related to the subjects of my research, my maternal grandparents, I am innately emotionally tied to their individual stories. Kornhaber and Woodward state that, “there is a natural, organic relationship between the generations that is based on biology, verifiable psychologically and experienced as feelings through emotional attachments” (xx). I find this relevant to my own memory of my relationship with my nonno and nonna, especially since I was only able to have them in my life until I was six and fourteen, respectively. This set of childhood and adolescent memories may affect how I choose to represent their history, because I do not hold recent memories of either of them. As time passes, positive memories and events are more likely to be remembered over unpleasant ones (Walker, Vogl and Thompson 399). Therefore, I cannot be completely objective when I select images and approach the act of writing about my own grandparents.

Another influential layer I must take into account in my project is that my grandparents are both deceased. Although one’s own memory, according to Nora, is in permanent evolution, (8) first-hand accounts of memory are generally valued when gathering information about an individual’s life. Unfortunately, I do not have access to primary sources for my grandparents’ stories. In order to substitute for the words (both spoken and written) of my grandparents, I turned to their closest living relatives—their children. My mother and my two aunts currently act as my main source of biographical information for this project. Of course, this means that I must take into account the memories of three different people. When recalling and describing events, my mother and aunts may rely on their psychic realities (mental spaces created with memories, wishes, fears and fantasies) to remember biographical events (Burgin 118). Although my mother and her sisters were raised in the same environment, several factors such as birth order may cause siblings’ perceptions of their parents to be different (Salmon 73). For example, my aunt Melissa was born when my grandparents were close to middle age. This factor may lead her memory of her parents to be notably different from her sisters’ reports. My mother Ornella, on the other hand, was born fifteen years earlier to a 21-year old, first-time mother. I assume that my nonna’s parenting style must have changed between raising her first and third child over a decade apart. This aspect is one of several that may alter how each of the sisters remembers growing up. Since my mother is the oldest daughter and the fact that I am in much more frequent contact with her than my aunts, she acts as my first and main source for information about my grandparents’ lives. This is yet another recognized but unavoidable bias that affects what information I receive and how I treat my own project going forward.

In terms of retracing location, I cannot accurately glean what my grandparents felt about their homeland and Canada. Brah claims that the same geographical location can acquire different meanings for individuals and can change over time (208). This may have been true for my grandparents, but I cannot assume what their attitudes were towards the two countries. While both my nonna and nonno were involved in the local Italian-Canadian community, they may have experienced residual trauma or a “condition of terminal loss” when relocating to a new country (Burgin 117). My grandparents did identify the value of staying in Canada—likely to give their children a “better future”—although this term is vague and the true reasons can never be confirmed directly by my grandparents.

After addressing the physical boundaries of my project (I have no direct access to my grandparents, only to their children and not to any other relatives or close friends of my grandparents) and the intangible nature of memory, I must consider the implications and problematic aspects of the main object of study for this project: the photograph. Although I cannot assume that my grandparents were aware of the presence of a camera in every photograph, the lens may have influenced how my grandparents presented themselves in these images. Several studies have proven that both humans and animals adjust their behaviour under surveillance (Wicklund 234). There are also notable gaps in the chronology of remaining photographs. For instance, I do not currently possess any images from the actual journeys of migration of either of my grandparents. The pre-selection of photographs that I could use for my project had already been narrowed down before I began this research. This is because photographs can disappear, go missing or be destroyed intentionally or through time and decay. Levin and Uziel bring up several aspects to consider before using a photograph as a historical source, such as who the photographer is, why the image was taken, who is present and what photographs are missing (266). These are all questions I will consider when selecting and analyzing a range of final photographs in my project.

As this introduction attests, there are numerous angles from which to analyze the variables (and issues) surrounding my project, from the social-political to the psychological and personal. All of the ideas mentioned here will be considered in the final creation of my project, to ensure an enriched and critical representation of my grandparents.

Identifications:

Ornella Osborne (née Binotto) – eldest child of Rino and Pierina Binotto

Vania Zadro (née Binotto) – middle child of Rino and Pierina Binotto

Melissa Binotto – youngest child of Rino and Pierina Binotto

Bibliography

Brah, Avtar. Cartographies of Diaspora: Contesting Identities. London and New York: Routledge, 1996, pp. 204-208.

Burgin, Victor. In/Different Spaced: Place and Memory in Visual Culture.

University of California Press,1996, pp. 117-121

Cancian, Sonia. Families, Lovers, and their Letters: Italian Postwar Migration to Canada. University of Manitoba Press, 2010.

Iacovetta, Franca. Such Hardworking People: Italian Immigrants in Postwar Toronto. McGill-Queen’s University Press, 1992.

Kornhaber, Arthur and Kenneth Woodward. Grandparents, Grandchildren: The Vital Connection. Transaction Publishers, 1981.

Levin, Judith and Uziel, Daniel. “Ordinary Men, Extraordinary Photos.” Yad Vashem Studies XXVI (1998): 266.

Nora, Pierre. “Between Memory and History: Les Lieux de Mémoire.” Representations, Special Issue: Memory and Counter-Memory, no. 26, 1989, pp. 7-24.

Salmon, Catherine. “Birth order and relationships, family, friends and sexual partners.” Human Nature, Vol. 14 (1), 2003, pp. 73-88.

Walker,Faster Than Pleasantness Over Time

W. RICHARD WALKER, RODNEY J. VOGL

and CHARLES P. THOMPSON

Kansas State University, USA

Autobiographical Memory: Unpleasantness Fades

Faster Than Pleasantness Over Time

W. RICHARD WALKER, RODNEY J. VOGL

and CHARLES P. THOMPSON

Kansas State University, USA

Walker, Richard and Rodney J. Vogl and Charles P. Thompson. “Autobiographical memory: unpleasantness fades faster than pleasantness over time,” Applied Cognitive Psychology, Vol. 11, 1997, pp. 399-413

Wicklund, Robert A. “Objective Self-Awareness.” Advances in Experimental Social Psychology, Vol. 8, 1975, pp. 233-275

Family

“Both [Rino] and [Pierina] grew up in a time when the war caused challenges and poverty for their families. However, they had many stories from their childhoods—usually using humour to get through the hardships. Their experiences gave them the courage to make their way in a new country. While they both had traditional upbringings, they were both working, hands-on parents. They missed their families dearly, but they also learned that they could ‘never go back’, especially after visiting Italy years afterwards. They never lost their love for the beauty and more sociable lifestyle that they left behind.” – Ornella

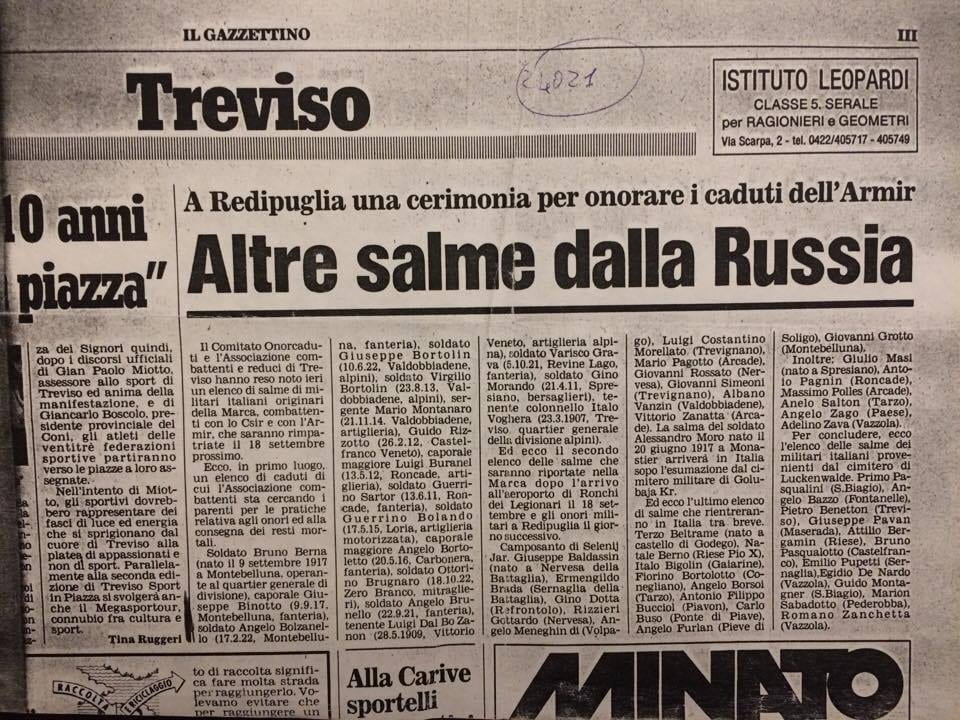

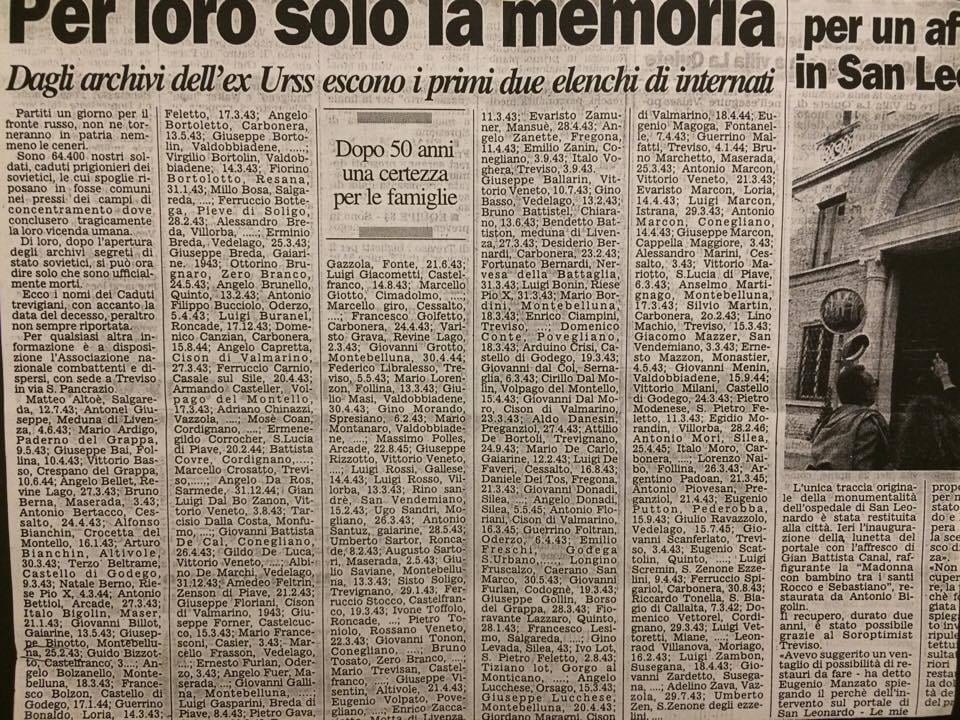

Born a decade apart in 1928 and 1938, respectively, Rino and Pierina both grew up in Veneto, Italy. Within their families, Pierina and Rino lived with linked lives, a term used to describe how the experiences of one family member affect all others in the family throughout their lives.1 In Italian families, interconnectedness is often a fundamental characteristic.2 Of course, having linked lives becomes a more complicated concept once some family members migrate to another country and others stay behind. Both Pierina and Rino experienced family losses early in their life. Pierina’s mother and father passed away within three years of each other, when she was still a teenager. Rino’s older brother, Giuseppe, went missing during WWII. It was revealed, years later, that he had died as a POW in Russia. “Family” portrays Rino and Pierina as they relate to their own families, and offers a look into the oldest of photos and documents within the project.

1. Stassen Berger, Kathleen. Invitation to the Life Span. Worth Publishers,2009, pp. 415.

2. Smolicz, Jerzy. “Core Values And Cultural Identity.” Ethnic & Racial Studies, Vol. 4, no.1, 1981, pp.75.

Binotto family portrait. Rino is pictured third from the left, in the front row. [Approx. 1938, Italy]. Photo provided by: Melissa

Carrer family portrait. Pierina stands in the centre. [Approx. 1950, Italy]. Photo provided by: Melissa

Pierina (second from the left) and her three sisters. [1967, Italy]. Photo provided by: Melissa

Pierina poses with her two brothers. [Date unknown, Guelph, Canada]. Photo provided by: Melissa

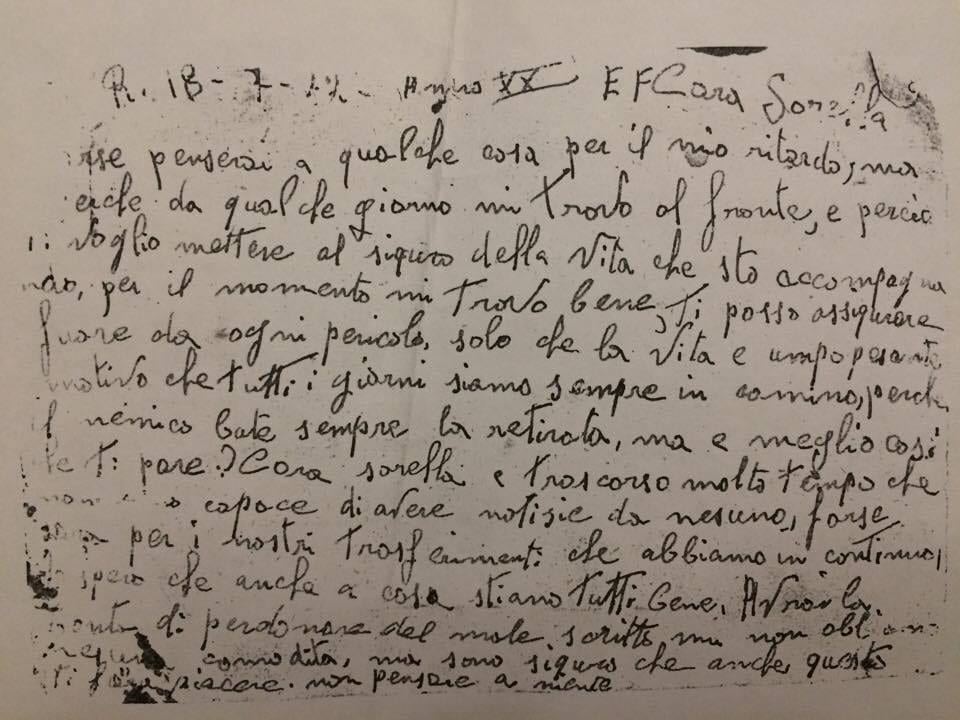

Front of postcard written by Rino’s older brother Giuseppe, addressed to their sister. [July 18, 1942, location unknown]. Photocopy provided by: Melissa

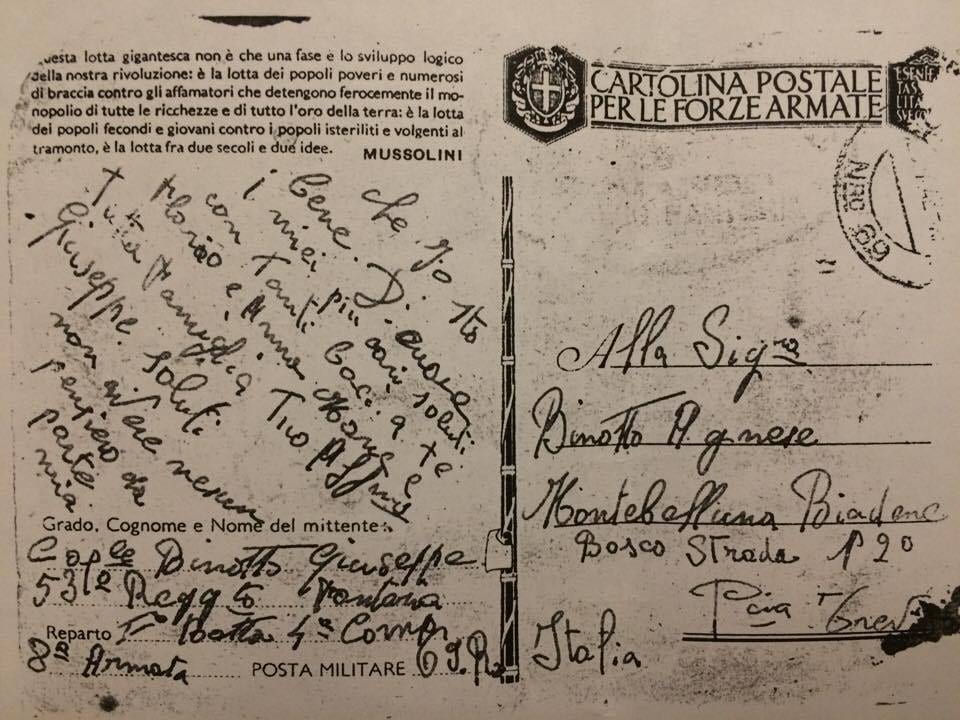

5b. Back of postcard written by Rino’s brother Giuseppe, addressed to their sister. [July 18, 1942, location unknown] Photocopy provided by: Melissa

Il Gazettino newspaper article [SP1] detailing the names of the missing soldiers. [1990s, Treviso] Photocopy provided by: Melissa

Il Gazettino continued[SP2] . “Giuseppe Binotto” appears near the bottom of the first column on the left. [1990s, Treviso]. Photocopy provided by: Melissa

Rino Binotto Bio

Rino Binotto

In 1928, Rino Binotto was born to a family of ten children in Montebelluna, Veneto, Italy. As the youngest of four brothers, he was supposed to receive a full education but was taken out of school to help with the family farm when his older brothers went to war. Although Rino’s teachers paid a visit to his parents to change their minds because he was academically strong, he remained home. This was the first step in changing his destiny.

When he was 24, he realized that with his three surviving brothers now back form the war, he would be unlikely to inherit any land. He could also not buy land due to the postwar economic depression. This led him to discover a Canadian company that was recruiting hardworking young men to help develop the Canadian railway. His plan was to work for a few years to earn enough money to be able to come back to Italy and become independent. In 1952, Rino arrived by boat in Halifax with several other young men. First in his family to move to Canada, Rino emigrated with just his suitcase—no savings and no relatives. For a few years, he laid rail in Northern Ontario, and while he loved the natural beauty of the province, he found living on the railway isolating. Too proud to admit defeat and return home, he decided to move to southern Ontario.

Ending up in Toronto, Rino worked in construction, but realized the big bustling city was not for him either. That is why he moved to Guelph, a city with a large Italian immigrant population. He started working at the Beardmore leather tannery in Acton, along with a friend of his. On weekends, they would hitchhike to surrounding areas to pick apples. Rino sent the money he earned home to his family so that they could set up a savings account for him. After four years of hard work and sacrifice, he returned home to find that his brothers had borrowed the money to help keep the family farm going.

Although this was a shock, Rino continued to have a good relationship with his family. While in Italy, he met Pierina Carrer and they instantly clicked. After a three-month courtship, he proposed and married her in Venegazzu. It was time for a fresh start, so Rino returned to work in Canada. Pierina followed six months later in 1957. Two years later, Ornella, their first child, was born. In 1962, they had their second child, Vania. In Canada, Rino developed lifelong friendships with other immigrants and became a founding member of Guelph’s Italian Canadian Club. While he and his wife had begun to settle in Canada, in 1967, they (along with their two daughters) visited Italy to scope out the job situation. After comparing the economic climates of their hometown and the life they had built in Canada, they decided to permanently reside in Canada. They believed this would lead to greater opportunities for their children. When they returned, they bought their second home and in 1974, had their third child, Melissa. Rino and Pierina would only see their homeland together one more time in the mid 1980’s.

When Rino was 58, the plant he had worked in for 35 years closed down, causing stress for him. Fortunately, he had an early pension and found a part-time job with a friend doing renovations, which he enjoyed. In his late sixties, he fully retired. At 74, Rino died of a massive heart attack. Over two hundred people attended his funeral, many of whom told his daughters how he was a well-respected figure in the community. While he was alive, Rino broke many stereotypes of the Italian father by sharing parental and household work. He embraced Canadian pastimes by helping his daughters learn to skate—although he didn’t know how to himself. At the same time, he kept Italian traditions alive by keeping his own garden, and making his own wine and salami with friends. Till the end, he remained the rock of the family and always told his girls to keep looking ahead.

Pierina Carrer Bio

Pierina Carrer

Pierina Carrer was born in 1938 in Venegazzu, Veneto, Italy. She had seven siblings. Pierina was named after the older brother she never met, who was not yet two years old when he passed away from pneumonia days after Pierina’s birth. She left school after a certain time, like all her siblings, to go to work and support the family. Growing up, Pierina loved the beautiful mountains and forests she lived near. She was a confident person who questioned the status quo, such as why the local priest insisted women wear long sleeves to church even on the hottest of days. When she was 16 years old, tragedy struck and Pierina lost her father to a severe head injury sustained from a motor vehicle accident. Because her father died, Pierina had to give most of what she earned to help the family.

Two years later, her best friend wanted to set Pierina up with her brother. At a dance, Pierina was instantly attracted to Rino, who was friends with her best friend’s brother. While Rino’s family embraced her and welcomed her, Pierina’s mother was reluctant at first to accept Rino because she knew he was working in Canada. They were married in Venegazzu soon after, and honeymooned at lake Garda. Then, while Rino returned to work in Canada, Pierina lived with his family for six months until she joined him. Pierina emigrated by ship, and went through New York City in October of 1957. From New York City, she took a train to Toronto and met Rino and a couple of his friends. Shortly after arriving in Canada, Pierina (now nineteen) went looking for work despite knowing no English. She got a job working as a seamstress in a factory, and began developing a social circle through church and work. Pierina wanted to bring her mother to Canada to live with herself and her husband, but fate had other plans. Her mother died five months after Pierina arrived in Canada in another motor-vehicle related accident.

The next year, in May 1959 she had her first born, Ornella. In 1962, she had her second child, Vania. In the early 1960’s, after her second daughter was born, Pierina and Rino helped one of Pierina’s brothers immigrate to Canada. He lived with them for a while and later they brought her youngest brother over as well. In 1967, the couple went back to Italy to decide whether to stay in Canada or return home permanently. They ultimately decided to remain in Canada. In 1974, Pierina had her third child, Melissa. Except for the year she took off of work to have Melissa, Pierina constantly worked. She became fully bilingual and ended up speaking more English to her children as they grew older. In the 1990s, Pierina travelled back to Italy on her own to attend the wedding of a relative and visit her older brother who was dying of cancer. She retired at the age of 60 and continued to be very involved with her grandchildren.

Unfortunately, Pierina was widowed at 64, when her husband died of a massive heart attack. Pierina herself passed away at 72 from cancer and several health complications. When she was alive, Pierina sustained her culture in Canada by cooking northern Italian meals and taking pride in her home. She was also unique because, unlike many of her cohorts, she continued working after having children, and both her and Rino took pride in being a double-income household. Although she had lived a life full of tragedies, Pierina was known for her sense of humour, a trait that she passed down to her children to help get them through difficult times and see the brighter side of life.

Identity

Identity

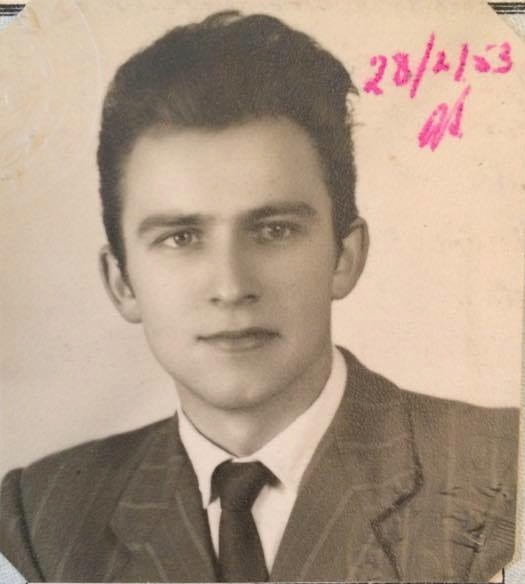

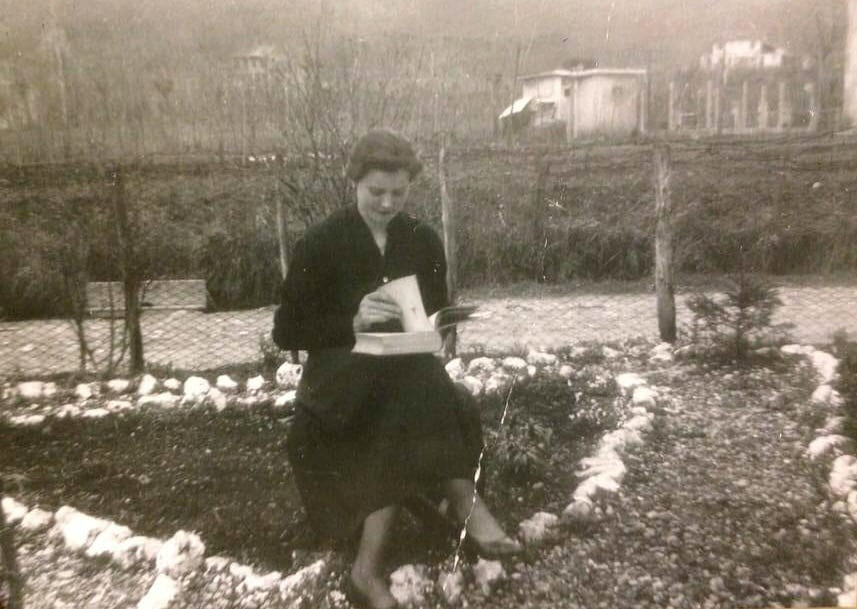

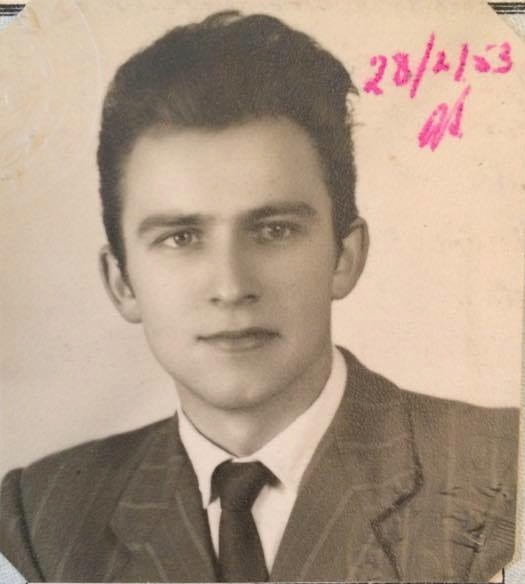

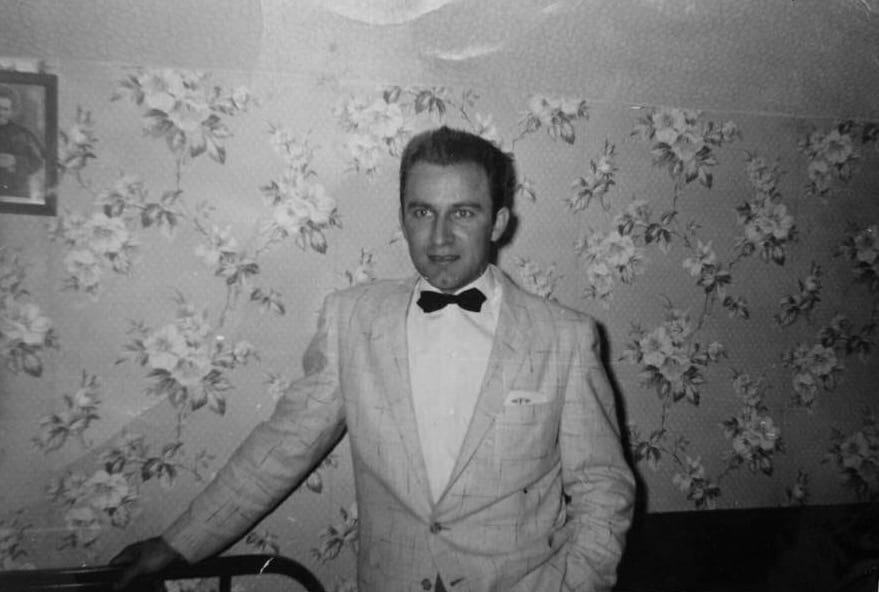

While Pierina and Rino are shown throughout this project as children in their families, husband and wife, parents and grandparents—they possessed their own individual identities that are significant to explore. Ethnic identity, for instance, plays a vital role in a person’s overall sense of self and can change overtime according to social circumstance1. Intersections of the young immigrants’ early exposure to Canadian life and the reactions of the receiving Canadian society would have influenced both their identities and well being.2 Gender also played a role in their identity formation. Resembling the Virgin Mary at the Annunciation, book (Bible?) in hand; Pierina embodies the modest ideal of a young Italian woman3 in one particular image4. The seriousness fades in the next photo5, however, as she sports fashionable sunglasses and a smile. Perhaps gender influenced Rino’s confident stance in another photo6, a stark contrast to his wife’s demeanor from the photo taken in her backyard4. Nevertheless, Pierina challenged stereotypical identities by continuing to work and raise children throughout her life. “Identity” focuses on snapshots of Rino and Pierina on their own.

1. Stassen Berger, Kathleen. Invitation to the Life Span. Worth Publishers,2009, pp. 352

2. Phinney, Jean, et al. “Ethnic Identity, Immigration, and Well-Being: An Interactional Perspective.” Journal of Social Issues, Vol. 57, no.3, 2001, pp. 494.

3. Iacovetta, Franca. Such Hardworking People: Italian Immigrants in Postwar Toronto. McGill-Queen’s University Press, 1992, pp. 80.

Title : Famiglia Binotto 8 Source: N/A Publisher: University of Guelph Type: Photograph License: REB compliant. Material collected in accordance with the Certification of Ethical Acceptability of Research Involving Human Participants Rights Holder: Alaina Osborne

Title : Famiglia Binotto 7 Source: N/A Publisher: University of Guelph Type: Photograph License: REB compliant. Material collected in accordance with the Certification of Ethical Acceptability of Research Involving Human Participants Rights Holder: Alaina Osborne

Title : Famiglia Binotto 6 Source: N/A Publisher: University of Guelph Type: Photograph License: REB compliant. Material collected in accordance with the Certification of Ethical Acceptability of Research Involving Human Participants Rights Holder: Alaina Osborne

Title : Famiglia Binotto 5 Source: N/A Publisher: University of Guelph Type: Photograph License: REB compliant. Material collected in accordance with the Certification of Ethical Acceptability of Research Involving Human Participants Rights Holder: Alaina Osborne

Title : Famiglia Binotto 4 Source: N/A Publisher: University of Guelph Type: Photograph License: REB compliant. Material collected in accordance with the Certification of Ethical Acceptability of Research Involving Human Participants Rights Holder: Alaina Osborne

Title : Famiglia Binotto 3 Source: N/A Publisher: University of Guelph Type: Photograph License: REB compliant. Material collected in accordance with the Certification of Ethical Acceptability of Research Involving Human Participants Rights Holder: Alaina Osborne

“Identity” captions

1. Pierina’s portrait from an Italian identification card. [1957, Italy] Photo provided by: Melissa

2. Pierina reads outside her family home. [1956, Venegazzu] Photo provided by: Melissa

3. Pierina sports sunglasses and smiles for the camera. [1956, Italy] Photo provided by: Melissa

4. Rino’s portrait from an Italian identification card. [1951, Italy] Photo provided by: Melissa

5. Standing confidently, Rino is pictured outdoors in Guelph, Canada. [Date unknown] Photo provided by: Vania

6. Rino enjoyed looking his best, according to Ornella. [July 1957, Canada] Photo provided by: Vania

Legacy

“I remember as a little kid, my dad would ask if I wanted to go to the beach. We would phone my friends up and go to Wasaga. We stayed all day, played in the water and ate fried chicken—those were some of the best memories of my life…[Pierina and Rino] let us make our own decisions and learn from our own mistakes. They were affectionate and had infinite patience, always looking at the positive side of life.” – Melissa

After getting married, Rino and Pierina began to form their own family unit. The promise of a bright and prosperous life for their future children led the young couple—along with thousands of other Italian migrants—to Canada1. They had three children, all of which were born in their new homeland. In 1959, Rino and Pierina welcomed their first daughter, Ornella, to the family. Three years later, Vania was born. In 1974, they had their third daughter, Melissa. Years later, as grandparents, Rino and Pierina’s involvement would help shape the lives and well-being of their five grandchildren.2 “Legacy” illustrates Rino and Pierina with their descendants as they build a home by fostering feelings of security, familiarity, community and hope.3 This category showcases a few of the ways in which the immigrant couple embraced Canada, including celebrating holidays such as Halloween and visiting famous Canadian landmarks.

1. Iacovetta, Franca. Such Hardworking People: Italian Immigrants in Postwar Toronto. McGill-Queen’s University Press, 1992, pp. 197.

2. Cline, Ruth. “Books for Adolescents: The Grandparent Connection in Young Adult Literature.” Journal of Reading, Vol. 32, no. 6, 1989, pp. 568.

3. Hage, Ghassan. “Migration, Food, Memory and Home-Building.” Memory: History, Theories, Debates, edited by Susannah Radstone, Bill Schwarz, Fordham University Press, 2010, pp. 418.

Title : Famiglia Binotto 17 Source: N/A Publisher: University of Guelph Type: Photograph License: REB compliant. Material collected in accordance with the Certification of Ethical Acceptability of Research Involving Human Participants Rights Holder: Alaina Osborne

Title : Famiglia Binotto 18 Source: N/A Publisher: University of Guelph Type: Photograph License: REB compliant. Material collected in accordance with the Certification of Ethical Acceptability of Research Involving Human Participants Rights Holder: Alaina Osborne

Title : Famiglia Binotto 19 Source: N/A Publisher: University of Guelph Type: Photograph License: REB compliant. Material collected in accordance with the Certification of Ethical Acceptability of Research Involving Human Participants Rights Holder: Alaina Osborne

Title : Famiglia Binotto 20 Source: N/A Publisher: University of Guelph Type: Photograph License: REB compliant. Material collected in accordance with the Certification of Ethical Acceptability of Research Involving Human Participants Rights Holder: Alaina Osborne

Title : Famiglia Binotto 21 Source: N/A Publisher: University of Guelph Type: Photograph License: REB compliant. Material collected in accordance with the Certification of Ethical Acceptability of Research Involving Human Participants Rights Holder: Alaina Osborne

Title : Famiglia Binotto 22 Source: N/A Publisher: University of Guelph Type: Photograph License: REB compliant. Material collected in accordance with the Certification of Ethical Acceptability of Research Involving Human Participants Rights Holder: Alaina Osborne

“Legacy” captions

1. Pierina holds Ornella on the day of her Baptism. [1959, Guelph, Canada] Photo provided by: Melissa

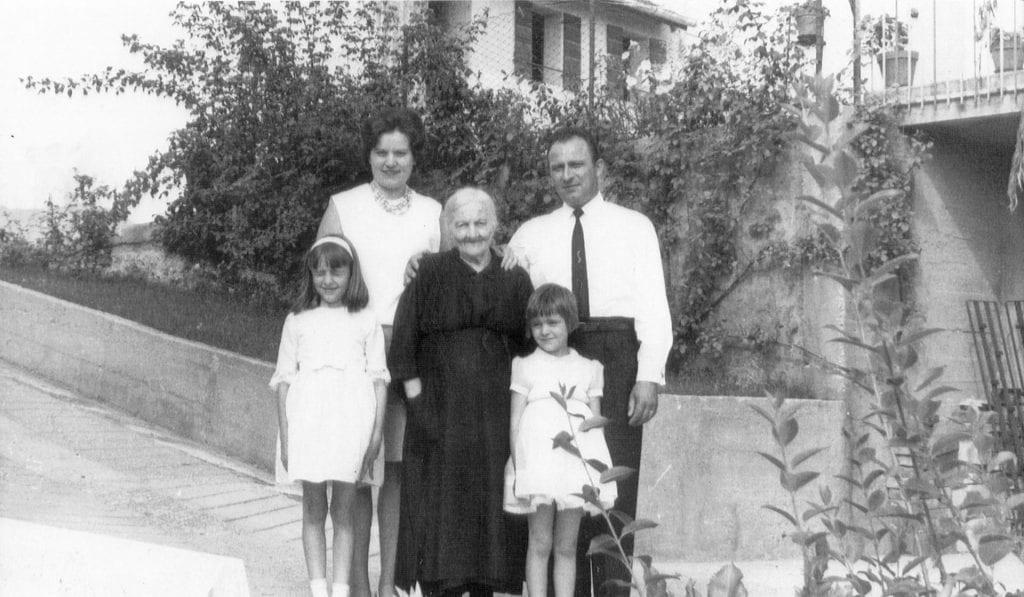

2. Vania and Ornella with their parents on a visit to Rino’s mother, Eva. [Montebelluna, 1967] Photo provided by: Melissa

3. The entire nuclear familystands in front of their house. [1975, Guelph, Canada]. Photo provided by: Melissa

4. Rino, Pierina and Melissa pictured visiting a famousCanadian landmark. [1979, Niagara Falls, Canada] Photo provided by: Melissa

5. Pierina embraces three of her grandchildren, who are dressed up warmly for Halloween. [October 31, 1991, Guelph, Canada]. Photo provided by: Ornella

6. Rino, Pierina, their descendants and their families pose for a photo. [2000, Guelph, Canada]. Photo provided by: Ornella.

Love and Marriage

“[Rino] was attracted to [Pierina] right away and vice versa. They had a very short courtship, about one month…they met and decided to take a chance on their instinct and get married before he went back to Canada. They were very different people but fundamentally they agreed on the important things in life. Both had the same sense of humour.” – Vania

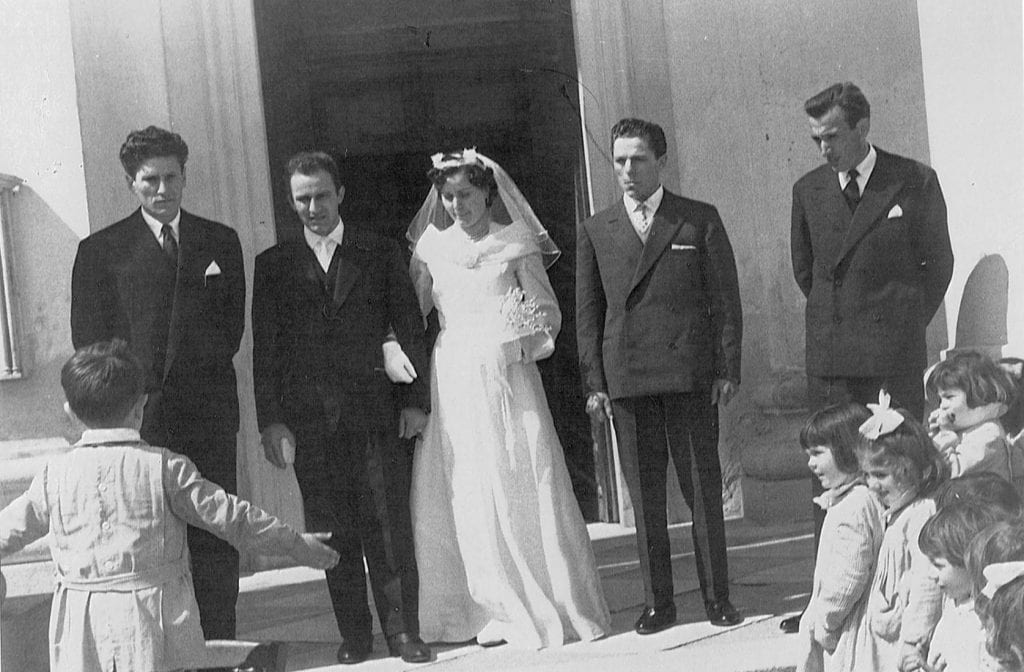

Marriage—the sacrament that creates a foundation for family—was an essential part of Catholic life in Italy during the 1950’s.1 Pierina Carrer and Rino Binotto fell in love and became engaged shortly after their first meeting in 1956. They were wed on April 13th, 1957 in Venegazzu and remained married until death. Rituals, such as Rino and Pierina’s wedding, can be seen as performances with prescribed actions and outcomes.2 Although a sense of ritual, tradition and structure was certainly present at their ceremony, the complicated range of emotions3 felt by young newlyweds who were going to be separated again (when Rino later returned to Canada) were also likely present. In “Love and Marriage”, Catholic customs are visible: from the bride’s white dress to the groom’s hands clasped in prayer. This category also offers glimpses into Rino and Pierina’s life together as a couple whose passion grows into commitment, a development gradually created through shared responsibilities, decision-making and caregiving.4

1. Rosinal, Alessandro and Romina Fraboni. “Is marriage losing its centrality in Italy?” Demographic Research 11 (2004): 149-172.

2. Feuchtwang, Stephen. “Ritual and Memory.” Memory: History, Theories, Debates, edited by Susannah Radstone, Bill Schwarz, Fordham University Press, 2010, pp. 281-298.

3. Cancian, Sonia. Families, Lovers, and their Letters: Italian Postwar Migration to Canada. University of Manitoba Press, 2010.

4. Stassen Berger, Kathleen. Invitation to the Life Span. Worth Publishers,(2009).

Title : Famiglia Binotto 23 Source: N/A Publisher: University of Guelph Type: Photograph License: REB compliant. Material collected in accordance with the Certification of Ethical Acceptability of Research Involving Human Participants Rights Holder: Alaina Osborne

Title : Famiglia Binotto 24 Source: N/A Publisher: University of Guelph Type: Photograph License: REB compliant. Material collected in accordance with the Certification of Ethical Acceptability of Research Involving Human Participants Rights Holder: Alaina Osborne

Title : Famiglia Binotto 25 Source: N/A Publisher: University of Guelph Type: Photograph License: REB compliant. Material collected in accordance with the Certification of Ethical Acceptability of Research Involving Human Participants Rights Holder: Alaina Osborne

Title : Famiglia Binotto 27 Source: N/A Publisher: University of Guelph Type: Photograph License: REB compliant. Material collected in accordance with the Certification of Ethical Acceptability of Research Involving Human Participants Rights Holder: Alaina Osborne

Title : Famiglia Binotto 28 Source: N/A Publisher: University of Guelph Type: Photograph License: REB compliant. Material collected in accordance with the Certification of Ethical Acceptability of Research Involving Human Participants Rights Holder: Alaina Osborne

Title : Famiglia Binotto 29 Source: N/A Publisher: University of Guelph Type: Photograph License: REB compliant. Material collected in accordance with the Certification of Ethical Acceptability of Research Involving Human Participants Rights Holder: Alaina Osborne

“Love and Marriage” captions

1a. A teenaged Pierina smiles at the camera on her first trip to Rome, Italy. [Date unknown]

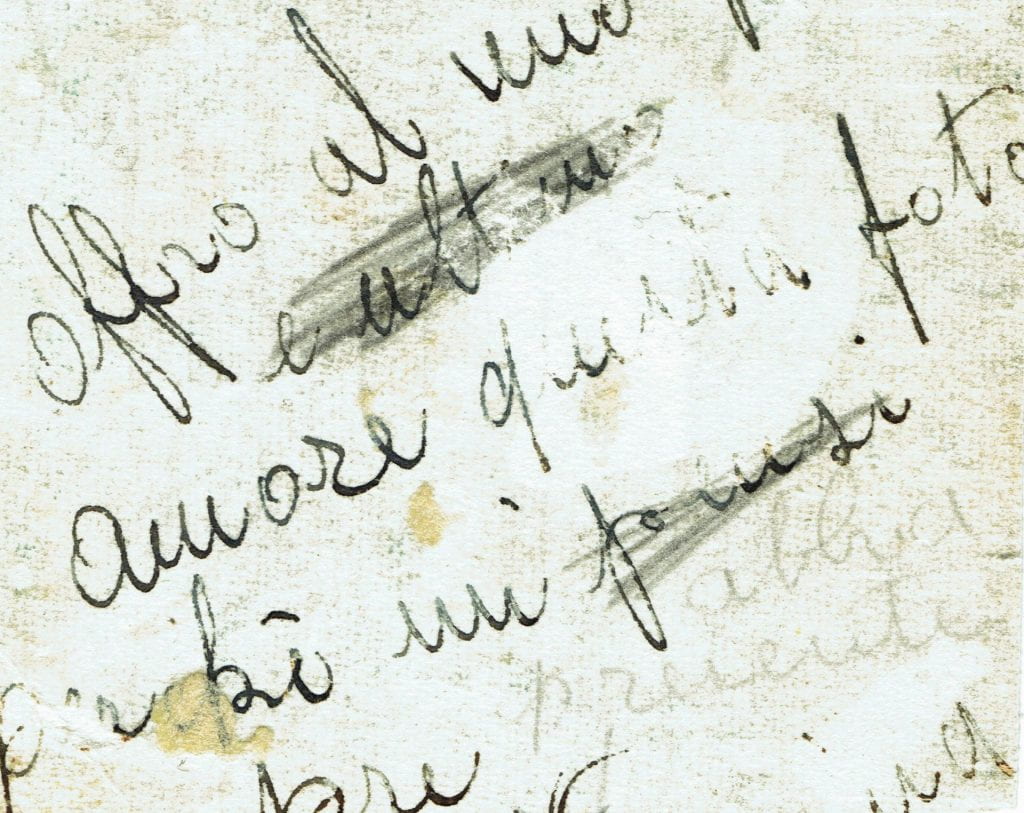

1b. Writing found on the back of Pierina’s photo, which may have been sent to her husband while he was working in Canada. The original photo appears to be cropped. [Existing dimensions: 4.5cm by 6cm] Translation: “I offer my love with this photo” Translation by: Ornella. Photo provided by: Melissa

2. At the altar waiting to receive the Communion with Rino’s best man. Rino and Pierina purportedly appealed to the local priest to allow them to be married during Lent. [April 13th 1957, Venegazzu, Italy] Photo provided by: Melissa

3. A happy moment shared between newlyweds at the entrance of the church. [April 13th 1957, Venegazzu, Italy] Provided by: Melissa

4. Songs and poems performed by local schoolchildren. Nuns who knew Pierina’s mother arranged this unique performance, which moved Pierina to tears, according to Ornella. [April 13th 1957, Venegazzu, Italy] Photo provided by: Melissa

5. The couple attends a formal event. Pierina’s dress is a soft pink colour, according to Ornella’s memory. [February 1958, Location unknown, Canada] Photo provided by: Melissa

6. Celebrating their 25th wedding anniversary. [April 13th, 1982, Guelph, Canada] Photo provided by: Melissa

Artistic Representation

“The contemporary recalls, re-evokes and revitalizes the past”1

—Giorgio Agamben

Throughout my research, I have re-examined my grandparents’ lives not only through academic reading and reflection, but also through visual representation. My studio work has been informed and inspired by the photographs, artifacts and theoretical and historical writings explored during the making of this project. In “Artistic Representation”, I engage and interact with the family archive to create works that infuse representation with the artist’s/descendant’s expressive gestures. The work explores how personal objects can be translated through artistic mediums to take on a new meaning2. Can a painting hold both the trace of the granddaughter (whose hand created the painting) and the grandparents (whose photograph was used to create the painting)? Does tracing my nonna’s handwriting bring a greater sense of understanding or mystery to my memory of her? What does it mean to draw objects used by my great-grandfather, a man I never met and know virtually nothing about? When viewing this body of work, the audience is encouraged to contemplate these questions and consider their relation to their own grandparents, whether they knew them or not.

1. Agamben, Giorgio. “What Is an Apparatus?” and Other Essays. Stanford, Stanford University Press, 2009, pp. 39-54[SP1] .

2. Bienart, Katy. “Reading Between the Lines: Artistic Approaches to the Family Archive.” Jewish Culture and History, Vol. 15, nos. 1-2, pp. 6-26

Title : Famiglia Binotto 1 Source: N/A Publisher: University of Guelph Type: Photograph License: REB compliant. Material collected in accordance with the Certification of Ethical Acceptability of Research Involving Human Participants Rights Holder: Alaina Osborne

Title : Famiglia Binotto 2 Source: N/A Publisher: University of Guelph Type: Photograph License: REB compliant. Material collected in accordance with the Certification of Ethical Acceptability of Research Involving Human Participants Rights Holder: Alaina Osborne

“Artistic Representation” captions

1. Osborne, Alaina. My grandfather’s and great-grandfathers’ pipes. 2016. Charcoal on paper. 18”x24”

2. Osborne, Alaina. Portrait. 2016. Acrylic. 30”x30”

3a. Osborne, Alaina. Offro al…amore/I offer…love. 2016. Ink, charcoal on vellum. 5’x6’

Process of selecting images

My main corpus for this project will be made up of photographs and images of my grandparents that represent their life before and after moving to Canada. There was a vast amount of photographs that I went through with the help of my aunt and mother to narrow down what was the most important. After discussing the different options for categorizing photographs at our Tuesday meeting, I decided to compartmentalize the lives of my grandparents into three themes: Marriage and Love, Family and Growing Up, and Legacy. I found that a non-linear set of categories was helpful so that I could broaden my understanding of my grandparents’ experience rather than try to site chronological events. I also chose to do broad themes instead of a strict linear set of classifications because it is more difficult to pinpoint exact dates of photographs than letters, for example, which often will have the date written on them.

Because I am working with the histories of two people, I chose a larger portion of photographs for each grandparent that I will eventually narrow down. If there were similar photographs of the same subject matter, I chose images that I felt best represented both the emotions of the subject and their physical surroundings. For example, I chose to include a photograph from my grandparent’s wedding where they are laughing with each other, so that personality can shine through. In another category, I chose a photograph of my grandparents visiting Niagara Falls with their third child to show how they explored and were interested in Canadian landmarks.

The themes themselves are also fluid in their meaning. For example, the Marriage and Love category represents marriage and love in the literal sense, for Pierina and Rino together, as well as the marriage between two countries, Italy and Canada. This is why I decided to choose photographs from their wedding day, and photographs of the two visiting Italy in their later years. This was my solution to the issue of trying to separate Canada and Italy. I could not have one category for each country because my grandparents did return to their homeland and of course, had an ongoing relationship with both nations.

For the second category, Family and Growing Up, I take a more literal approach and include photographs of each of their families as well as photographs of my grandparents themselves roughly between the ages of eighteen and their early twenties. For my third category, Legacy, I include photographs of my grandparents settling in Canada, as well as their children and grandchildren. This was a very important aspect for me to show because I am interested in how their life decisions to uproot and move to Canada have led to the quality of life I, my cousins and my siblings are able to have. Through my collection of images, which may be supplemented with other documents including passports, postcards and milestone certificates (such as getting married) I hope to paint a diverse picture of the lives of my grandparents.

List of Items:

- 189 photographs (both old and new)

- 4 Bocce trophies

- 2 certificates of Canadian citizenship

- 2 smoking pipes (from nonno’s father and grandfather)

- 5 passports (2 Italian, 3 Canadian)

- $25 (before the Loonie was created)

- 1 elementary school report card

- 2 handwritten work training documents

- 1 record of marriage

- 1 family document to become members of Sacred Heart church

- 2 Italian ID cards (1951, 1957)

- 7 telegrams (from 2002, offering condolences)

- 1 letter

- 2 postcards

- 2 newspaper articles (one detailing missing names of soldiers, one recent article detailing trip to Treviso)

- 1 invitation to first child’s wedding

- 1 civil record