“Sixteen Men” and the Paymaster Mining Tragedy of 1945

The disregard for basic worker safety has resulted in various accidents that have shaped the history of mining, including the Paymaster Mining Tragedy of 1945. On February 2nd, 1945 at 7:55 AM, the hoisting rope of the Number Five shaft at Paymaster Consolidated Mine broke, causing the cage to fall over 1700 feet. The accident lead to the instantaneous death of fourteen men, with two others dying shortly after being recovered from the site. The primary cause of the accident was found to be loss of strength in the hoisting rope “caused by internal wear and corrosion of the wires” (Tower et al. 35). Failure of the cage dogs – an emergency safety mechanism on cages designed to pierce into the wooden timbers of the shaft should it begin to fall – was noted as the secondary cause. Further research revealed that “the Machinery Record Book recorded no inspection since the middle of June 1944” (Tower et al. 36). Thus, for nearly eight months, minimal efforts were taken to preserve the safety of workers. Among the sixteen men lost was Italian worker, Nicola Suppa. Suppa, aged 44, was among the men who died instantaneously. He was a cage tender with Paymaster Mine since 1933 and was married with one daughter (“Funerals of Men”).

Research into the Paymaster Tragedy was conducted following recognition of the history of accidents within the mine. The father of one victim, Eino Niemi, was killed during a similar accident within the same mine and, shockingly, within the same shaft only two months prior to the Paymaster Tragedy (“Funerals of Men”). These men were of Finnish descent, but their story reflects the lack of attention that was often presented toward the safety of non-English speaking individuals. The short time frame between both incidents raises awareness toward the mass number of workers that were often injured or killed on job sites due to the negligence of those with power.

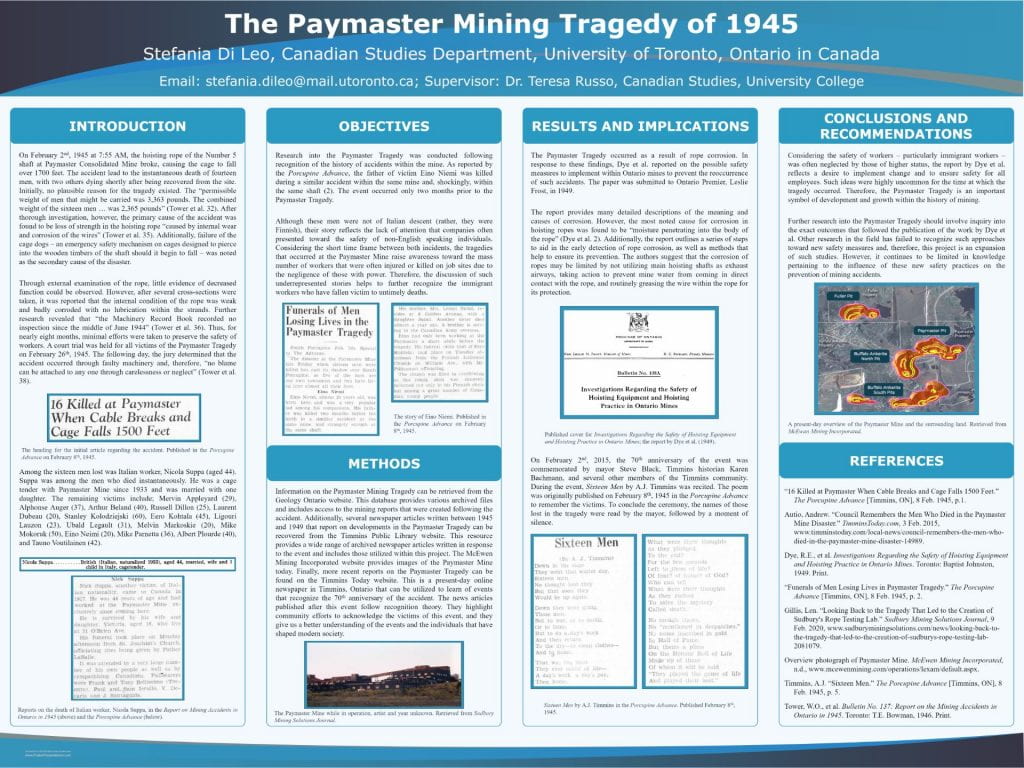

In 1949, Dye et al. responded to the Paymaster Tragedy by submitting a report to Ontario Premier, Leslie Frost. The report outlines steps to aid in the early detection of rope corrosion, as well as methods that help to ensure its prevention and, therefore, the reoccurrence of such accidents. The authors suggest that the corrosion of ropes may be limited by not utilizing main hoisting shafts as exhaust airways, taking action to prevent mine water from coming in direct contact with the rope, and routinely greasing the wire within the rope for its protection (Dye et al. 5). The 70th anniversary of the Paymaster Tragedy was commemorated by Timmins mayor, Steve Black, on February 2nd, 2015 (Autio). During the event, Sixteen Men – a poem written by A.J. Timmins in 1945 – was recited, followed by the names of all men lost in the tragedy.

Archived mining reports that were created following the Paymaster Tragedy can be retrieved from the Geology Ontario website. Archived newspaper articles that were written between 1945 and 1949 and the report on developments in the accident can be recovered from the Timmins Public Library website. The McEwen Mining Incorporated website provides images of the Paymaster Mine today. Finally, the Timmins Today website, a present-day online newspaper in Timmins, Ontario, outlines more recent events that recognize the Paymaster Tragedy. These sources highlight community efforts to acknowledge the victims of this event. Additionally, these new sources provided by the community give us a better understanding of the events and the individuals that have shaped modern society.

In conclusion, the Paymaster Tragedy is an important symbol of development and growth within the history of mining. The report by Dye et al. reflects a desire to implement change and to ensure safety for all employees during a time in which these needs were often neglected by those of higher status. However, future research should inquire into the degree to which these new safety practices influenced the prevention of mining accidents. It is hoped that this research has raised awareness for the workers – who were not only of Italian descent, but of various origins – that were killed trying to earn a living and provide for their families. We must continue to remember their stories for the creation of our modern society would not have been possible without these individuals.

Stefania Di Leo

University College at the University of Toronto, 2020

Appendix

Sixteen Men by A.J. Timmins

Down in the cage

They went that winter day,

Sixteen men.

No thought

But that soon they

Would be up again.Down they were going,

Those men.

Not to war or battle,

Or to fame,

But to do a day’s work

And then return

To the dry – to clean clothes –

And to home.That was the most

They ever asked of life –

A day’s work, a day’s pay,

Then home.What were their thoughts

As they plunged

To the end?

For the few seconds

Left to them of life?

Of fear? of home? of God?

Who can tell

What were their thoughts

As they rushed

To solve the mystery

Called death.No medal theirs.

No “mentioned in dispatches.”

No name inscribed in gold

In Hall of Fame.

But theirs a place

On the Honour Roll of Life

Made up of those

Of whom it will be said

“They played the game of life

And played their best.”

Works Cited

Autio, Andrew. “Council Remembers the Men Who Died in the Paymaster Mine Disaster.” TimminsToday.com, 3 Feb. 2015, www.timminstoday.com/local-news/council-remembers-the-men-who-died-in-the-paymaster-mine-disaster-14989.

Dye, R.E., Healy, R.L, and Parker, R.D. Investigations Regarding the Safety of Hoisting Equipment and Hoisting Practice in Ontario Mines. Toronto: Baptist Johnston, 1949. Print.

“Funerals of Men Losing Lives in Paymaster Tragedy.” The Porcupine Advance, Timmins, ON, 8 Feb. 1945, p. 2.

Timmins, A.J. “Sixteen Men.” The Porcupine Advance, Timmins, ON, 8 Feb. 1945, p. 5.

Tower, W.O., et al. Bulletin No. 137: Report on the Mining Accidents in Ontario in 1945. Toronto: T.E. Bowman, 1946. Print.

How to cite this research

Di Leo, Stefania. “‘Sixteen Men’ and the Paymaster Mining Tragedy of 1945.” In Archival Research of Italian-Canadian Immigration and Culture, supvr. Teresa Russo, issue 2: Italian Fallen Workers, University of Guelph, April 2020, Guelph. Italian-Canadian Narratives Showcase Fallen Workers – Italian-Canadian Narratives Showcase (italianheritage.ca)(ICNS), Sandra Parmegiani and Nivashinee Ponambalum.