Italian Canadian Women in the Workplace

Samantha Greco focuses on the workplace after World War II during the postwar boom years of Italian immigration to Canada. This period preceded a dark time in Canadian history when Italian, German, and Japanese people were interned in camps after Great Britain joined the allied forces. The Canadian government’s War Book of 1939 permitted the arrest and internment of enemy aliens during war time when “real proof” could be determined for suspected enemies of Canada. However, Antonino Mazza demonstrates in his introduction to The City without Women that real proof of disloyalty was never established for the roundup of many Italians. The Canadian government further expanded the arrest of “enemy aliens” to include Canadian citizens. The violence against Italians and Italian Canadians swept across Toronto, Montreal, and Vancouver in their homes and workplaces, while Italian-owned businesses faced destruction from violent riots. Greco places her study within this perspective when Italians faced discrimination due to Benito Mussolini’s decision to support Hitler, causing the detainment of Italian and Italian Canadian citizens across Canada.

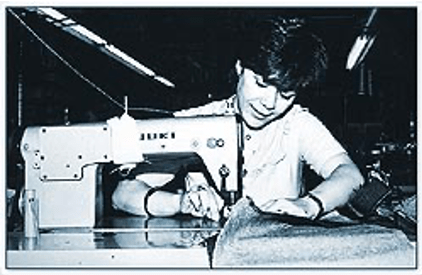

Within this evaluation of the difficulty Italians faced finding employment, Greco spotlights women in the workplace, especially in the clothing industry where other immigrants, who were established in Canada by the 1950s, provided opportunity for Italian and Japanese workers. Canadian archives and literature indicate moments in Canadian history when women were employed in various Canadian industries; however, employment in factories were the major employers for female immigrants as Greco demonstrates in her research. We know from Michael Ondaatje, who researched documents in the City of Toronto Archives and fictionalized the lives of immigrants in Toronto in The Skin of a Lion, that Italian women were working in Canada as early as the 1930s even before Italian men were interned at Petawawa. His chapter on Caravaggio highlights a mushroom factory where the “punch cards of the workers” were mainly Italian and “some Portuguese” and in particular Italian women like Giannetta or Angelica. Additionally, in this volume of Archival Research of Italian-Canadian Immigration and Culture, Daniella Pace demonstrates women’s employment in factories, finding themselves in tailoring and sewing workrooms throughout Toronto during World War I and World War II.

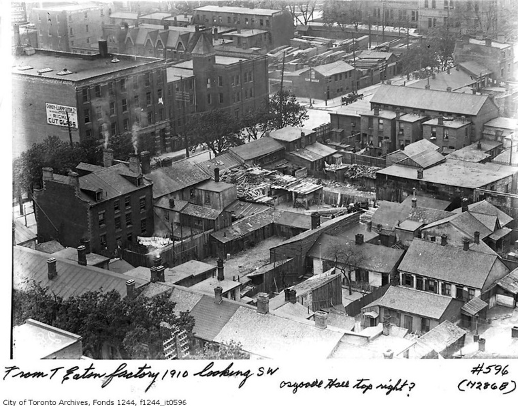

On the other hand, the story of Grace Bagnato and Elena Maccaferri Randaccio demonstrate employment in other industries from 1920-1940 for Italian Canadian women. Bagnato’s work experience is unique in that she became the first Italian-Canadian woman court interpreter in 1921, representing in the courtroom at Osgood Hall the various immigrants who settled in the Ward in Toronto by interpreting their voices from their various ethnic languages into English. It was her exceptional acquisition of languages that suited her for the position as she learned the languages of those immigrants moving to the Ward in the 1920s-1930s.

Bagnato was able to explain cultural norms to people living in the Ward, while clarifying cultural misunderstandings for new immigrants to magistrates and law enforcements. She even represented Italian men during interment years in the local court, explaining that they were not fascist sympathizers or fifth columnists. Randaccio, in contrast, explains in her diary how she had to find a way to maintain her farm and care for her children during her husband’s internment when individuals, such as Bagnato or Randaccio’s cousin, could not keep the Italian men out of prison. The families of the interned men could not receive government support with a status of enemy aliens. She writes:

I found myself alone and I understood that with two children, the cows, the chickens, the pigs, and the fields I could never run the farm on my own. The farm produced well in those days, and for a few days, I tried desperately to manage on my own. The neighbours came to give me a hand….It was easier to rent the farm out….With a lump in my throat, a fist full of dollars and a lot of goodwill we left for the city of Montreal. Because of the children, I could not go out to work. So I rented two rooms and tried to do work from home. I tried various jobs from seamstress to hairdresser, to sewing on uniform insignia….Ciccio [a cousin]…convinced me to put the kids in the daycare run by nuns, and he found my work in a restaurant. I got good tips and after a few months, I was promoted to cash register (Ricordo bene quella sera, 31-32).

Her diary describes how she began working as a seamstress, hairdresser, and waitress to provide for her children. Italian women were finding themselves in the workplace for most of the same reasons to support their families when their husbands were interned or fallen workers. After World War II during the boom years of immigration from Italy to Canada, it was not unusual to find women working for a second income to increase families’ earnings, especially if women were already in the workplace during the war years. As Randaccio explains in Ricordo bene quella sera, she was a changed woman and her husband would have to recognize her anew.

Greco documents further these contributions of Italian women after 1940, focusing on the years marked the “postwar boom years” of Italian immigration to Canada. Her research demonstrates that Italian Canadians and Japanese Canadians still suffered discrimination shortly after the war when the Wars Act was lifted and during this period a hostile employment environment existed for these ethnic groups. Nu-Mode, however, provided opportunities for the Italian and Japanese communities in the fashion industry where Greco’s grandmother, Pasqualina Porzio, contributed to the industry forming on Adelaide and Bathurst Streets in Toronto. Her research records more evidence of women in the workplace through the personal archive of Pasqualina Porzio and by creating an oral history of her grandmother’s experience.

Teresa Russo

University of Toronto, 2019

Fond 1244, Item 596). See top right corner for the location of Osgood Hall.

in Montreal, circa 1970 (Archives of Casa d’Italia, Montreal, Quebec). Photographer unknown.

Works Cited

Mazza, Antonino. “Introduction to the English Edition.” The City Without Women, by Mario Duliani and translated by A. Mazza, Mosaic Press, 1994, pp. ix-xxv.

Ondaatje, Michael. In the Skin of a Lion. Vintage Canada, 1996.

Ore, Jonathan and Veronica Simmonds. “Amazing Grace,” produced by CBC Radio, Radio Interactives-The Doc Project. December17, 2018. https://www.cbc.ca/radiointeractives/docproject/amazing-grace.

Pace, Daniella. “Italian Canadian Women During War Periods.” In Archival Research of Italian-Canadian Immigration and Culture, supvr. Teresa Russo, issue 1: Italians on the Frontiers, University of Guelph, October 2019, Guelph (academic poster, www.italianheritage.ca/list-of-projects/immigration). Italian-Canadian Narratives Showcase (ICNS), Sandra Parmegiani and Sharon Findlay.

Randaccio, Elena Maccaferri. “Ricordo bene quella sera” in The Anthology of Italian-Canadian writing, ed. and trans. by Joseph Pivato, Guernica, 1998, pp. 31-33.

Scardellato, Gabriele. “Introduction.” The Darkest Side of the Fascist Years: The Italian-Canadian Press, 1920-1942, by Angelo Principe, Guernica, 1999, pp. 9-18.

Sweeney, Sylvia. “An Act of Grace,” produced by Peter Raymont, A Scattering of Seeds: The Creation of Canada. Season 3, episode 34. White Pine Productions, 2000.