Introduction: Italians on the Frontiers

The first volume of exhibits in Archival Research of Italian-Canadian Immigration and Culture, positioned on the theme of Italians on the Frontiers, considers the employment and contributions of Italians to industrial projects during the various waves of emigration from Italy to Canada. After initial phases of exploration and early contact, there were four waves of Italian immigration to Canada centered on working in industrial projects and building Canada’s infrastructure: the period of small settlement with seasonal migration (1800s-1914); the period between wars (1918-1940); the Second World War (1940-1950); and the period after World War II when the Enemy Alien Act was lifted, known as the “post-war boom” years (1951-1971) of Italian immigration to Canada.

Millions of Italians had left their homeland and emigrated to the Americas since the 1800s where work was available on railways and in mining during years of early settlement. The early migration was mainly to the United States, but a small significant migration pattern was recorded during this period to Canada to work with the Canadian National Railway, Canadian Pacific Railway, and the Dominion Coal Company. In the Niagara region, Italian men found work building the Welland Canal and Paper Mill, forming settlements and cultural centers with other immigrants around the canal and nearby industrial projects in the Niagara, Colborne, Thorold and St. Catharines areas. The construction of rails and canals lasted into the 1940s and continued to draw Italian immigrants to the work sites.

Statistics from the Italian archives show that an average of about 100 Italians arrived in Canada per year between 1876 and 1885, an average of 1,500 Italians arrived per year between 1886 and 1888, and under 400 Italians reached the shores of Canada from 1888 to 1898, signifying a year decline (Balletta et al, 354). By 1901, however, there were 11,000 incoming Italians to participate in projects building Canada’s early infrastructure; this migration pattern continued to 1915, and by 1911 a total of 60,000 Italian migrants were recorded in Canada. The Italian Ministry of Foreign Affairs registers a dramatic decline in emigration between World War I and Word War II and during the years of the great depression: an average of only 3,000 Italian migrants arrived in Canada between 1916 and 1925 and an average of 1,300 between 1926 and 1935 (Balletta et al, 354). However, by 1951, the Italian population in Canada had grown to 152,245, and during 1951 to 1961, about 26,000 Italians migrated to Canada a year (Jansen, 30).

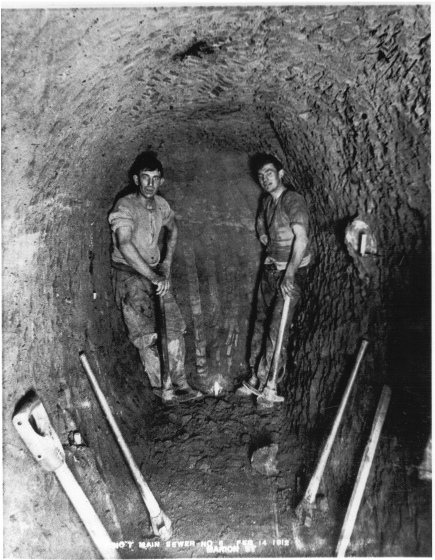

Italians were employed in the greatest vulnerable conditions as outdoor workers and in manual labour on the trainways, railways, canals, roads, port installations, hydro installations, lumbering and harvesting in the Canadian heartland, and clearing bush throughout Canada’s woodland for construction of transport systems by 1918. In addition, Italians worked in the mines, excavation projects, sewers, farmes, and in construction trades as painters, plasterers, moulders, and decorators in cities across Canada. Although most of their employment was physical labour, Italians also worked as street vendors, in entertainment, as artists, and soon became business owners by the 1930s. For example, Robert Harney also documents Italians employed as entertainers, street musicians, and artisans in the mid-nineteenth century in cities outside of Italy, such as Francesco Rossi providing gelato in Toronto as early as 1847. Angelo Principe details Italian businesses in construction, shoe repair shops and shoe shining, fruit vendors, grocery stores, and barbershops in the later twentieth century, a time when Italian immigrants were still clearing bush and laying down tracks. Principe asserts, “The first Italian fruit vendors who sold their goods from carts on the streets of Toronto at the turn of the twentieth century had become storeowners by the twenties and thirties” (3). In addition, Bruno Ramirez demonstrates in his study of Italian workers on the Canadian Pacific Railway in Montreal that even construction workers, such as Antonio Funicelli and Vincenzo Monaco, became store owners in the late 1920s after a few years of painful manual labour with the CPR (27). By 1931, a year after the start of the great depression, Il Direttorio italiano (published by the Italian Information Bureau of Toronto) records 736 Italian-owned businesses in Toronto alone and a few Italian professionals in the city, including two lawyers, five medical doctors, two optometrists, and one dentist. Olga Pugliese’s research further documents the contributions of skilled artisans of Italian origin for mosaic projects, such as the Mosaic Ceiling of 1933 located in the Rotunda at the Royal Ontario Museum—an important artistic venture in the main national museum at the time—and the Thomas Foster Memorial Temple (1935-1936; north of Uxbridge), named as one of the unusual things to see in Ontario by Ron Brown (Even More Unusual Things to See in Ontario, 1993).

During World War II both the governments of Canada and Italy halted immigration, decreasing dramatically Italian labour for the industrial projects. Mussolini, embarrassed of Italy’s citizens leaving to rebuild North America, stopped emigration to Canada, and the Canadian government in fear of fascism passed the Enemy Alien Act, which took Italian and Italian Canadian men from their families and from their trades. Italians lost their jobs and a means to support their families during these years of internment. After the removal of the Enemy Alien Act in 1947, the men returned home but faced difficulties finding employment. Four years later, Italian immigration grew in record numbers: between 1951 to 1961 the population increased roughly from 150,000 to 450,000, and again Italians began building Canada, driving Canada’s postwar economic boom. Italian and Italian Canadian contributions were also seen in the wine industry, agriculture, and hospitality. In fact, Niagara Region saw the ushering of a new era in winemaking with Donald Ziraldo and partner Karl Kaiser in the 1970s. Ziraldo, a Canadian born to parents of Italian descent, founded the Vintner’s Quality Alliance (VQA) and established the Cool Climate Oenology and Viticulture Institute (CCOVI) at Brock University for the scientific study and practical skills in oenology and viticulture.

These are the stories the students represent in their research from CPR in Montreal to Donald Ziraldo in Niagara, from contributions as manual labourers to factory workers and opera pioneers. They consulted documents and archives at Library and Archives Canada, Toronto Public Library, Historical Collections (Toronto) and the Archives of the City of Toronto, Archives and Special Collections at Brock University, Clara Thomas Archives and Special Collections at York University, City Planning and Development Services of Toronto, the Dominion Bureau of Statistics in Canada, among museum exhibits, films, and documentaries. Students also document personal collections of Italian immigrants in Toronto and Niagara Falls, creating oral histories by interviewing Italian Canadians in their communities, mainly their family members who migrated to Canada after Italy was left in ruins following World War II.

The first volume of this journal is influenced by Robert F. Harney’s research on the experience of Italian migrants in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries when twenty-five million Italians left their native country to venture out onto new frontiers. Harney viewed the Italian travelers, sojourners, street musicians or suonatori ambulanti, migrant workers as entrepreneurs on the frontiers rather than cafoni and unskilled peasants. He identifies an “ethnic inferiority complex” among Italian North American intellectuals, who grew embarrassed at the thought of this early immigration history to Australia, South America, the United States, and Canada when Italian men dug ditches and accepted physical labour in comparison to their admiration of an “Italian élite of talent” that includes professional artists, poets, musicians, and experts in the fields of law, government, commerce, and academia (such as Lorenzo Da Ponte, Constantino Brumidi, Andrea Palladio, Adelina Patti, Henry Mancini, Tetrazzini, Caruso, Toscanini, Frank Capra, John Ciardi, JoAnn Falletta, Nicole Marie Passonno Scott, Bonnie Tiburzi, Frank Sinatra, Dean Martin, and even explorers like Giovanni Caboto). Harney’s research establishes respect for the “wandering civilizers,” who others (like Paolucci Caboli) describe as vagabonds (The Italian Immigrant Experience, 11). Harney describes the large mass of immigration from Italy to various countries as a flow of immigration in which travelers and migrants found “talent to opportunity” and settled the frontiers with their skills:

Italians with different trades have brought civilizing skills to other peoples’ frontiers. The Italian language lacks a word for Italians overseas as a collectivity Italia oltremare does not describe the phenomenon that words like Diaspora for the Jews, and Polonia for the Poles do. But, in a sense, a unity of migration experience does exist in space: from Thunder Bay and Trail in Canada, to Rosario and Sao Paolo in South America, to Utah, Tampa and the Australian outback; and in time, from the later Middle Ages to the present. The same continuity shows itself in the immigrants probing for a chance to practice needed mestiere (skills) and survive; from the creation of the first caffé in Paris by a Sicilian in the sixteenth century to the appearance of the first wandering Italian ice cream vendor (gelati) in Scotland, and indeed, to that early Italian settler in Toronto, Francesco Rossi, who supplied ice cream for the Catholic Diocese (The Italian Immigrant Experience, 6; boldface is Harney’s emphasis).

Students realized that digging caves and removing bush made one of the largest contributions in Canada as Italians with other ethnic groups built the infrastructures that accommodate and sustain the various networks (of transportations, communications, sanitation, etc.) across the country. This labour enabled urban operations for city and rural living as the Roman aqueducts, roads, walls, and urban infrastructure created channels across an empire for its sustainability. Italians, additionally, through their “civilizing skills” introduced the arts (music, art, sculpture, dance and entertainment) and the manufacturing and importing of fine foods, fashion and cosmetics to cities around the world (Harney, The Italian Immigrant Experience, 7). The research in this volume modestly portrays some of these early contributions from the 1900s to 1970 in industrial projects as well as in music and viticulture.

Teresa Russo

Toronto, 2019

Italian Workers constructing a sewer (MHSO Collection, 1896-1914/ITA- 200373), photographer unknown.

Italian immigrants lay cobblestones on King Street in 1903 (MHSO Collection, 1896-1914/ITA-200372), photographer unknown.

Works Cited

Balletta, F et al. Un secolo di emigrazione italiane: 1876-1976. Rome: Centro Studi Emigrazione, 1978.

Bramble, Linda. Niagara’s Wine Visionaries. James Lorimer & Company Ltd., 2013.

Briani, Vittorio. Il Lavore Italiano Oltremare. Il Nouvo Sbocco Canadese, 10. Rome: Ministero degli Affari Estteri, 1975.

Direttorio Italiano, Ontario (Canada) 1931, prepared and published by Italian Information Bureau, 111 Elm Street, Toronto, ON.

Jansen, Clifford J. Italians in a Multicultural Canada. Canadian Studies, 1. Queenston, ON: Edwin Mellen Press, 1988.

“Francesco Rossi’s ice cream invoice to the Bishop,” 1847. Toronto diocesan archives.

Harney, Robert F. Italians in Canada. Occasional Papers on Ethnic and Immigration Studies, 1. Toronto: Multicultural Historical Society of Ontario, 1978.

Harney, Robert F. The Italian Immigrant Experience. Thunder Bay, ON: Canadian Italian Historical Association, 1988.

MHSO online archive. “The Global Gathering Place: An Overview of Italian Canadian History” The Multicultural Historical Society of Ontario, 2020. http://www.mhso.ca/ggp/Ethnic_groups/Italian/Ital_overview.html

Principe, Angelo. “The Fascist-Anti-Fascist Struggle in the Order Sons of Italy of Ontario, 1915-1946,” The Ontario Historical Society, Volume 106, no. 1, Spring 2014, pp. 1-33.

Pugliese, Olga Zorzi. “The Mosaic Ceiling of 1933 at the Royal Ontario Museum and its Craftsmen: The Untold Story,” Studies in the Decorative Arts, vol. 11.2, Spring-Summer 2004, pp. 59-77.

Pugliese, Olga Zorzi and Angelo Principe. “The Mosaic Workers of the Thomas Foster Memorial in Uxbridge.” JSSAC/ JSÉAC 28.1,2, 2003, pp. 25-30.

Ramirez, Bruno. “Brief Encounters: Italian Immigrant Workers on the CPR,” Labour/ Le Travail, vol. 17, Spring 1986, pp. 9-28.

Zucchi, John. Italians in Toronto: Development of a National Identity 1875-1935. McGill-Queen’s University Press, 1988.