Table of Contents

By Kyra Bates

Preface and Aknowledgement

As I entered my fourth year of my undergraduate degree, I was able to take various courses at the University of Guelph which not only allowed me to learn about facets of history I had not previously encountered, but to work with primary and previously unanalyzed sources for the first time. That year, I decided to enroll in a Scottish history course where I was introduced to the University’s collection of medieval Scottish manuscripts. Though previously I had not learnt much about this period of Scottish history, working with the manuscripts allowed me to discover my passion for graphology, preservation, and archiving. With no previous instruction in Latin or paleography, the course was a major learning curve, but the discoveries I made throughout the semester made it all worth it.1 The same year, while working with Dr. Sandra Parmegiani, I was introduced to a diary written by Gregorio Ceccato, an Italian soldier who enlisted in the army in 1917 and fought alongside his comrades in the First World War. The diary, never before studied, was lent to Professor Parmegiani by the Ceccato family in the hopes someone would have the opportunity to analyze it. I was lucky enough to carry forward this work.

When I began working with Dr. Parmegiani I had taken on the role of Research Assistant, managing the Italian-Canadian Narratives Showcase project. The website, which houses a collection of archives pertaining to the Italian community both in Guelph and in Canada, focuses primarily on preserving the stories of both individuals and their families.2 There are projects currently accessible on the site, including the Guelph Projects, written and created by students from the University of Guelph. As of 2023, there are also Community Projects stemming from all over Ontario and Alberta, and various projects focusing on the Archival Research on Italian-Canada Immigration and Culture. Though some of the stories collected in these projects, especially those in the Italian Heritage Project, may seem of little interest at first, they have proven to be a rich and valuable collection of information. While personal experiences might seem small when placed within the whole scope of history, they are necessary to understand the impact historical events had on those that came before us. Part of my research role while working for ICNS included beginning to examine the diary of Gregorio Ceccato. While at first it seemed I was only going to work on the diary as part of my role, making it easier for Professor Parmegiani and members of the Ceccato family to access and interpret it, I soon became invested in the story of Gregorio Ceccato and decided to focus my own time on researching the diary’s history.

I thus began this project while still an undergraduate student. The process of preserving Ceccato’s words and experience in a way that allowed anyone to access it was not easy at first. The process included not only working with a fragile historical artifact, the diary itself, but transcribing and translating Ceccato’s handwriting and dialect-inflected prose – which often contained errors and untranslatable words – into standardized Italian. When the first section of this diary was completed, it was uploaded to the ICNS website, where it can still be found along with newer sections as they are completed, in the hopes of making the story of Ceccato reach a larger audience.3 This project is the next step in working towards the larger goal of preserving and contextualizing the diary in its entirety.

When I began my graduate degree at the University of Guelph in the fall of 2021, I needed to decide what I wanted my final Major Research Project to be focused on. Having taken courses which discussed various periods of European and world history, I was at first unsure of which route I wanted to go. Classical studies and Antiquity were always of great interest to me, as was my newfound love of Scottish manuscripts and the Middle Ages. When I began my undergraduate degree, I also contemplated majoring in art history and doing a minor in film and media studies. Though I ultimately graduated with a Bachelor of Arts in European Studies with a minor in Italian, the interdisciplinary nature of my degree allowed me to explore these facets of history and everything in between them. Though not a period I had studied intensely before, working on this diary has provided me with a sense of purpose I feel lucky to have as a young researcher. As a lover of history and someone who deeply values her own ancestry, I can think of no better topic than one that allows me to preserve the story of an ordinary, yet extraordinarily interesting, figure of years past.

Before delving into the project, I must first give my thanks to those who have helped me along the way. First and foremost, I must give my thanks to Angelo Ceccato and the entire Ceccato family for entrusting me with this diary and allowing me to give life to the story of their ancestor. I will always be grateful for this opportunity and all I have learned in the process. I hope this project can help the family reconnect with their roots and learn more about a thrilling period of both Italian history and their own.

Secondly, I also want to give thanks to a few of the other amazing professors at the University of Guelph that have helped me not only with this project, but in my journey to completing my Master’s. Firstly, to Professor William Cormack, whose knowledge of the First World War and its study helped me immensely in the early stages of this project. Secondly, to Professor Susannah Ferriera from the History department, for showing me how rewarding it is to work with primary sources, and for fueling my love of archiving. And lastly, to Professor Alan McDougall, whose devotion to helping me on this journey not only supported this project but provided me with some of the sources that helped contextualize my research.

Finally, I want to give thanks to Professor Sandra Parmegiani. I first met Dr. Parmegiani when I was eighteen, having just started my very first semester of university with two courses taught by her. I have been lucky enough to have her as a professor in more courses than I can count and cannot thank her enough for everything she has helped me with throughout my time in Guelph as a student. This project, as well as virtually every other I have completed in my academic career, would truly be nothing without her. For allowing me to join you on the journey of evaluating this piece of history, thank you.

Introduction

In English historical discourse, there is a significant lack of research pertaining to the Italian perspective of the First World War. While there are many academic sources that investigate this, the majority of them are in Italian and thus not accessible to those who do not read or speak the language. While the First World War was substantially documented, Western and English sources pertaining to the war often focus on the achievements of the “bigger” Allies, prioritizing accounts written in English, and generalizing the large-scale events of the war. While Italy and its role in the war have been studied, it has often been overlooked in favour of a focus on the Triple Entente.4 This is seen for example in discussions on the German Spring Offensive5 of March to July of 1918, which often fail to mention the presence of multiple Italian divisions fighting alongside the other Allied soldiers.6 As such, English writings often give a general description of Italy’s part in the war, but do not reflect the experience soldiers had in the army. While this does help construct relevant and easy to understand reflections on the war, it overlooks the role of the Italian army, the important observations of individuals who lived through these events, and the impact they have on a nation’s identity. First-hand accounts of historical events allow researchers to understand and corroborate the events of history, even centuries after these events have occurred. As those who lived and fought during the time of the First World War are no longer with us, the only way to discover new information is through artifacts and writings we are lucky enough to still have. Analyzing, preserving, transcribing, and even translating first-hand accounts can continue to expand what is known about our own history. The Diary of Gregorio Ceccato is a document that shows how personal recounts of historical events can not only provide us with a new perspective, but also help us to see that nothing is as simple as the history books make it seem.

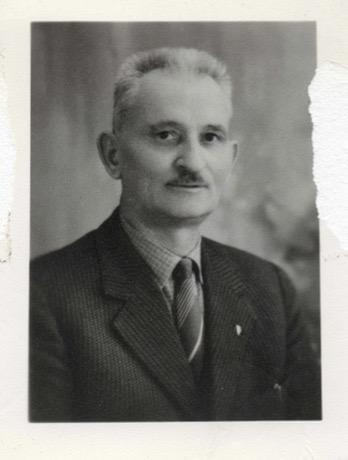

Gregorio Ceccato began his fight in Vittorio Veneto, a city just sixty kilometers north of Venice, Italy. His diary, along with the story of his experience, was forgotten with the diasporic movement of his family from Italy to Canada. Born in 1898, Ceccato himself remained in Italy for most of his life, but his son Domenico came to Canada as a Landed Immigrant in 1951 at the age of twenty-two. Looking for a better life for himself and his betrothed Elda, Domenico traveled to Guelph, Ontario, Canada, bringing the diary with him so as to have a memento of his father on the journey. The two settled in Guelph and were married at the Basilica of Our Lady Immaculate on January 14, 1956. Only recently rediscovered amidst family heirlooms, the diary has not yet been read by the majority of the remaining Ceccato family, many of whom still reside in the Guelph-Waterloo region. Having long been disconnected from Italy, and unable to understand Ceccato’s dialect-inflected Italian (or standard Italian), the diary symbolizes a part of their family history that is, in its current state, inaccessible to them. Employing my background in Italian and European Studies, and with the aid of Dr. Parmegiani and the History department at the University of Guelph, I hope to bridge this gap and make Ceccato’s legacy not only available for the family to experience, but for all those interested in an original document written both in the trenches of Europe and in the tumultuous years that followed the Great War’s end.

During his time in the war, Gregorio Ceccato was an Ardito Officer in the Italian Army, meaning he specialized in the use of weaponry on assault missions.7 The name Arditi roughly translates to “the daring ones”, an embodiment of the high-risk nature of their role. As will be discussed further on, many of the missions Arditi would undertake were not only dangerous, but often deadly. As an Ardito, Italy’s version of the Stormtrooper8 , Ceccato’s war experience was one filled with the mechanical workings of cannons, guns, and machinery, unlike any that had been seen in Europe before. While Ceccato’s role as an Arditi Officer was short lived – as he was only active just over two years – his membership provided him with a community to be involved, especially during the interwar period. The Arditi became memorialized as the strength of the Italian Army, becoming a symbol not only for the power Italy commanded during the war, but a model for future groups aiming to embody the same. The special force even inspired the likes of those such as Benito Mussolini, who modeled his own paramilitary group, known as the Blackshirts, after the Arditi.9 Postwar, many former Arditi members – Ceccato included – would support the growing wave of Fascism in Italy, seeing in it a continuation of the freedom and power they once felt on the front lines.10

In keeping with the context of the diary and the role Gregorio Ceccato played within the war, this project aims not only to showcase and make accessible his experience but broaden what is accessible within English academia about the Italian Arditi. Not long after I began this research, I quickly became aware of the various difficulties I would encounter when trying to access research on the topic. There are other stories of Arditi that have been memorialized, even a few others which are formed from personal diaries, however none at this current time are accessible in English and most of them focus on a specific event or battle, rather than the overall memorialization of the individual experience of a former soldier.11 Though I am able to read and understand Italian sources, the lack of material available in English on the subject, as well as the lack of sources in Italian accessible to me through a Canadian university, made it clear that there were many gaps that need to be filled on this period. My hope is that this project will provide an important piece of historical research which will help supplement and maybe even encourage further discussion on the period. This limited project will focus on the experience of one individual and his place in history, allowing the words of Gregorio Ceccato to become part of a much larger discourse. In this Major Research Paper, I analyze a portion of the diary, and an even smaller fraction of Italian history from the period. The guiding principle in my choice of text used from the diary, was dictated by its contents. While the majority of the diary was written while Ceccato was fighting in the front lines, studying the diary has revealed that he continued to inscribe his thoughts within its pages long after the war ended. While the content of his writings changed drastically – going from cannon diagrams and rope lengths, to carpentry measurements and personal notes – his use of the diary carried on throughout the postwar decades.

The first section of this project will examine the diary as a historical object. For this, I will examine the role it plays in constructing not only the history of Ceccato, but that of the period he lived through. In this portion, I will also use material from some of the other sections of the diary, including one titled by Ceccato as “Giovani”, featuring what appear to be rules of the military code. Though the diary is penned in its entirety by Ceccato, many pages detail the inner workings of the machinery he would have worked with – the guns and cannons he would have been in charge of controlling – as well as what appear to be the words of superiors, possibly even transcriptions. A selected few of these pages will be used to demonstrate how Ceccato utilized the diary during his time in the army.

The primary section I will analyze is a letter he drafted in 1934 addressed to the dictator of Italy, Benito Mussolini. The purpose of Ceccato’s letter was to enlighten the Duce to his and his family’s struggles in the years following the war. He addresses the leader in the hopes of receiving help, something he feels he deserves as a former Ardito and devoted Italian patriot. His choice to compose the draft of his letter within the diary, rather than in a newer notebook or on simple paper pages, is particularly meaningful. While we have no way to know Ceccato’s exact reasoning for this decision, the choice can be read as an embodiment of a desire to carry on his legacy, to connect with his past, and even relate it to his current predicament. While the letter was written many years after the war’s end, it is an indispensable portion of the diary, telling us more about Gregorio Ceccato and his life than any of his war notes ever could on their own.

While the main portion of this project may in summary appear to simply contextualize a single letter written by a figure of the past, over two years of work have gone into understanding this patchy account of confusing language. Countless hours of research have been devoted to discerning not only the words of Ceccato, but the tone and function of this “simple” letter he wrote within an old diary. The process of creating this project required me to not only expand on Ceccato’s written words, but to learn how to interpret them – and at the same time – the terms of the period in which he wrote. Though I am unable to complete a comprehensive study of all pages of the diary within the confines of this project, it is my hope to do so in the future, and to be able to transcribe and translate all of its contents, as well as interpreting each of Ceccato’s various diagrams. For this Major Research Project, I will focus on the components which outline Gregorio Ceccato’s personal experience on the front lines and in the following decades, with the aim of both constructing Ceccato’s history and giving context to the experiences we can take from his writing.

The Diary as an Object

The study of memory has changed drastically over the last century, with historians now taking a deeper look into the benefits, and problems, that arise from viewing history through someone else’s lens. The first thing that comes to mind when we think of diaries is often that of a child or teen. During this pivotal time in one’s life, people often choose to write down their experiences as a way to consolidate their emotions and actions. Though Ceccato’s own work is far from a teenage diary filled with stories of friendship and young love, it embodies the very same desire to document his experiences. Throughout time, diaries have been kept for a variety of reasons, but more often than not, for the aim of preserving one’s own memories. Personal accounts of periods of history have contributed greatly to the way we understand what came before us. This can be seen through the impact the journals of figures like Anne Frank, Charles Darwin, Ahmad ibn Fadlan, and Marie Curie had not only on the chronicling of history itself, but on art, literature, travel, politics, science, and the way we understand our world in its entirety. To Ceccato, the diary is a personal memoir, a collection of oaths, an artillery manual, a notepad, and everything in between. Being only 11.5 centimeters long by 7.5 centimeters wide, the diary would have easily been stored in Gregorio’s pocket, taken on his journey fighting in the war and even accompanying him during the many years that followed. As discussed in the Introduction, many difficulties arose during the process of analyzing Ceccato’s writings. With many soldiers sent away from their homes during the war, written correspondence accelerated as it was the primary way people could stay in touch with their loved ones. As such, many workers and peasants – like Ceccato himself began to write frequently for the first time, something demonstrated in the errors seen consistently throughout Italian written testimonies from the period.12

In the case of Ceccato’s writing, the difficulty in understanding his experience came from reading his handwriting, dissecting his use of grammar, and dealing with my own lack of prior knowledge on the weaponry he discusses. One of the primary concerns a researcher must have when attempting to summarize or present someone else’s work is that they must do so in a way that preserves the thoughts and opinions of the original writer. While grasping Ceccato’s style of writing and its various grammatical errors was a learning curve, having spent almost two years working on this object has allowed me to become confident I can provide plausible interpretations of what it is he wished to convey, not only to Mussolini in his letter, but to the memorialization of the events he lived through. Though many questions within Ceccato’s words remain unanswered (and very likely always will), through this research we can attempt to fill in some of the blanks. While to modern readers Ceccato’s diary reads at times mostly as a manual, it provides researchers like myself with valuable information about not only the artillery he was using, but what the personal experience of a soldier in Italy was like.

Many groups of soldiers were required to keep activity logs while they were fighting during the First World War. These documents are now often referred to as “war diaries”. Though there were personal diaries and accounts written during this time, many units kept group diaries as a way to record vital information that the entire unit would need to remember, creating individual unit-tailored manuals.13 This practice was one adopted by the Canadian Expeditionary Forces, The British Army, and many others, covering various theatres of the war.14 While these types of war diaries acted as manuals rather than personal stories of the fighting, they are relevant to this discussion as Ceccato’s diary follows, at least in part, this model. Though the Italian Army did not have its units keep diaries in the same way, images of other surviving war diaries from Italian soldiers show that the type of diary used was often similar to that of Ceccato’s, suggesting these notebooks may have been provided to soldiers as a part of their uniform.15 Further, there are other examples similar to that of Ceccato’s that demonstrate he was not alone in his quest to document the semantics of his journey.16 Though just a simple notebook that looks like any other you would find in a store, the similar size and colouring of these other examples – leather exterior, faint lines on pages, red colouring seen along the spine – supports this idea. If this was the case, then there was clearly some desire to allow Italian soldiers to document their experiences. Whether it be for the sake of allowing them to consolidate their emotions, or to create better trained soldiers, the outcome is the same. What sets Ceccato’s diary apart, however, is his continued use of the diary during the Italian Fascist dictatorship and beyond.

Ceccato wrote the majority of his diary while fighting on the North-Eastern front during the First World War and its pages chronicle what he learned while on the front line. While diaries can be an expression of personal thoughts and experiences, Ceccato primarily utilizes the diary as a war notebook, something exemplified in each of the sections within it. While the diary is not studied in its entirety within this project, its layout is important to understanding the way in which Ceccato utilized it. The diary has 132 pages in total, and can be divided into seven sections:

i. Pages 1 to 6 – The Opening Pages

ii. Page 7 – “Giuramento” (Oath)

iii. Pages 8 to 97 – Tactical and Weaponry Notes

iv. Pages 98 to 110 – “Giovani” (Young Men17 )

v. Pages 111 to 118 – Continued Tactical and Weaponry

vi. Pages 119 to 130 – Letter to Mussolini

vii. Pages 131 to 132 – Miscellaneous Notes

The first section features what can be described as the opening pages of the diary. These are the pages where Ceccato’s name, address, and information about his rank are noted. The seventh page can be considered as another section because it appears to divert from Ceccato’s own notes and leads the reader into a section he titled “Giuramento” (Oath).

This page is dated 13 July 1917 and contains an oath that Ceccato likely took upon joining the army. The 1907 edition of the Regolamento di disciplina militare (Military Discipline Regulation) features an oath identical to this one.18 Given that this oath pertained to the first article of the “Doveri Generali d’ogni Militare” (General duties of every Military) and that Ceccato transcribed the oath exactly, it is easy to assume this must have been one of the most important lessons in a soldier’s training.19 The sentence which follows the oath – which Ceccato did not write in his diary – declares that the oath must be retaken when a soldier is promoted to officer.20 It is possible Ceccato not only recorded this to remember what he committed to, but also – I like to think – in the hope he would need to say it again someday.

Spread across pages eight to ninety-seven are Ceccato’s various notes on weaponry, equipment, and techniques he used while fighting. Based on the dates, Ceccato updated and added to the section as he encountered and used different items while on the front lines. He describes the workings of rifles and mortars, lists the best tactics for using equipment, and notes important information he may need to remember, including the morse code alphabet.21 The diary thus became a personal instruction manual, no doubt of great value to him during both training and in combat. In this section, he demonstrates his desire to document all he can, carefully filling the pages with diagrams, various measurements, and even tables of information. Another one of these includes a portion he titled “Cordami” which details information about ropes such as length, diameter, maximum force, and what they were used for.22

The majority of Gregorio Ceccato’s diary is written in blue (now faded to look almost purple) and black ink, however the next section of the diary differs as it is written in red ink. Written across pages 98 to 110, the section titled “Giovani” stands out from the majority of Ceccato’s writing, only resembling the oath he transcribed on page seven. The tone and language of these pages suggest that Ceccato may have been transcribing the words of a superior. In the following section, where Ceccato drafted his letter to Mussolini, the style of writing used makes it clear that Ceccato’s own prose was far less formal than what is demonstrated here:

“Considerare per il vostro bene per il bene delle vostre famiglie ma soprattutto per il bene del paese, della nostra grande Italia, queste parole e resi forti dal convincimento del dovere, delle altre idealità di Patria, saprete affrontare, con animo sereno, pericoli disagi, privazioni, accettando volontariamente quella disciplina che costituisce la forza dell’Esercito, forza che sola può condurre alla Vittoria.”23

(Consider these words for the good of your own families but above all for the good of the country, of our great Italy, strengthened by the conviction of duty, of the other ideals of the country, you will be able to face, with a serene mind, dangers, hardships, deprivations, voluntarily accepting that discipline which constitutes the strength of the Army, strength which alone can lead to Victory.)

Gregorio Ceccato, War Diary of Gregorio Ceccato, 1917-1934, diary, ed. Kyra Bates and Sandra Parmegiani, Ceccato Family Collection, 109-110.

The commanding and assembling tone can easily be read as a speech or prepared text to be used by the military, something an officer may have said to his battalion as they trained. While the structure of the presumed speech is formal in nature, Ceccato’s spelling and use of grammar still falls behind, further demonstrating how these words were likely not his own. His choice to note down these phrases help paint Ceccato as a devoted soldier, one who was keen on learning – and remembering – all he could. While this section of writing does not quote the Regolamento di disciplina militare in exact words (as the “Giuramento” section did), much of the text resembles other portions of the “codice militare” (Military Code).24 While this speech was likely one that aimed at bestowing – and possibly even renewing in the case of those who had fought with the Italian Army before – a sense of duty onto soldiers, at times it also reads as a warning. Speaking of the discipline required to be a valiant soldier of the army, this section details a considerable number of crimes that can be punished under law; those obvious and not:

È bene quindi che tutti i soldati conoscano perfettamente quali sono le violazioni alle leggi che costituiscono reato e che vengono perciò punite col Codice militare. Alcune di esse sono già troppo evidenti e gravi per non capire subito a quali pene estreme conducano.25

(It is good then that all soldiers know perfectly what are the violations to the laws which constitute a crime and which therefore come punished by the Military Code. Some of them are already too obvious and serious to not understand immediately to which extreme penalty accompany.)

Ceccato, War Diary, 104.

While not constructed exactly to that of the manual, the third section of the Regolamento di disciplina militare, titled “Parte III: Punizioni Disciplinari – Norme Generali” (Part III: Disciplinary Punishments – General Rules), divulges the majority of the crimes and their punishments being described here.26 Ceccato’s choice to transcribe this entire discussion of thirteen pages suggests a desire to make sure he followed the rules while in action. It also implies he did not have access to his own copy or version of the “codice militare” so instead worked to make sure he had his own.

The subsequent section, making up only eight pages, is a continuation of Ceccato’s tactical and weaponry notes. Some pages within this section of the diary appear to be missing and out of order. While the diary still remains in fairly good condition, its fragility is apparent and great caution had to be taken when working with individual pages. While I did not attempt to reorganize some of the loose pages – a few of which ended up within the front matter of the diary – a complete and accurate sequencing of the pages may be part of continued work on this diary.

The last significant portion of the diary is constituted by Gregorio Ceccato’s draft letter to Benito Mussolini written in 1934. While the letter can be defined as a call for help to the Duce, it represents the most interesting and relevant section of the diary. As Ceccato aims to demonstrate to Mussolini why he is deserving of the help he asks for, he details his life during the years leading up to 1934.27 This postwar conceptualization offers more insight into Ceccato’s personal life to readers than any other page within the diary. Without the letter, we would know nothing about the man who kept this detailed diary of his tactical experience. The following section of this paper will discuss this letter in detail.

While history is often generalized and contextualized from a greater scope, it is both rare and important to see the events of history as they played out from the ground. In the words of Giovanni Levi: “The unifying principle of all microhistorical research is the belief that microscopic observation will reveal factors previously unobserved.”28 Imploring the concept of microhistory – as described and utilized by Carlo Ginzburg – I will examine how Ceccato’s letter to Mussolini, and even his diary as a whole, allows for the creation of a new way to look at this period of history, outside of the large-scale generalizations that readers are used to.29 Though Ceccato’s writings will never see the fame afforded to diaries such as those of Galeazzo Ciano30 discussing Italy’s most infamous leader, they allow us to understand more about the experiences of a former soldier during this interwar period and the difficulties that he experienced, making it all the more relatable.

For him, Mussolini was not only the leader of Fascism, but also someone who could potentially aid him in his time of need. Given that Ceccato’s correspondence never received a reply from Mussolini, we can also question how this opinion of “Il Duce” may have changed. Did he come to resent the supreme leader? He may have even lost his belief in the Fascist cause he so vehemently describes himself as being committed to. While some questions will always remain unanswered, it is up to researchers like myself to try and fill in the blanks.

Ceccato’s Letter to Mussolini

On March 19th, 1934, Gregorio Ceccato wrote the draft of a letter to Benito Mussolini, the Prime Minister and Duce of Fascism, asking for help. His letter, written in the back end of his diary and in the opposite direction, shows that his use of the diary continued long after the war’s end.31 While the pages written on the diary were a draft copy of the letter, his family believes that Ceccato did formally compose the letter and send it to the Italian dictator. In it, he chronicles his life and experiences during the war, his patriotism to the Italian cause and his various acts of heroism. Between 1918 and 1934,32 Ceccato lived in fascist Italy, where he and his family experienced hardship and he faced long bouts of unemployment. Though Ceccato was originally from Asolo, a town in the Veneto region sixty kilometers north of Venice, at this time he and his family lived in Vittorio Veneto, a larger city northeast of his birthplace, where his wife’s family had settled. As he describes in the letter, the family was forced to move in with his mother-in-law, who was generous enough to support them from 1918 to 1934. The economic climate in Italy made finding stable jobs difficult, and Ceccato himself worked in various industries to provide for his family. Though he discusses the trials he is facing in the aftermath of demobilization, the letter constitutes an ideal continuation of his experience as a soldier: a patriot and a citizen serving his country. Only after this account, does Ceccato ask Mussolini to assist him and his family. It is unknown if Mussolini ever received the letter, but the Ceccato family oral history records that an answer never came, nor the much hoped for help.

Contextualizing the Interwar Period from 1918 to 1934

Ceccato’s letter brings us into 1930s Italy. Before we can analyze the letter and its contents, we must first understand the period between 1918 and 1934, and what was occurring throughout the country politically, socially, and economically. Though Ceccato does present himself as being aligned with the fascist cause within his diary, a discussion of early Fascism and the part Benito Mussolini played in its development is critical to understand why Ceccato would have addressed his letter to the Italian dictator, and what his life as ex-Ardito soldier may have looked like. Shifting to the immediate postwar period, 1919 and 1920 are known in Italian history as the biennio rosso.33 In the years following the war, several of the countries involved in the conflict had to deal with the repercussions of what became a long and costly fight.34 Even though Italy was fighting alongside the Allies and was one of the so-called winners, the postwar period in Italy was not without struggle. Since 1918, there have been discussions which have focused on Italy and its status as a winner. Contrary to the sentiment of many people in other Allied European countries, such as Britain and France, many Italians felt as though they lost in the war.35 Gabriele D’Annunzio, an Italian writer, soldier, and ultranationalist, famously coined the term “vittoria mutilata” when describing the way Italian nationalists felt about the outcome of the Paris Peace Conference.36 With other European powers failing to provide Italy with the rewards promised in the Treaty of London in exchange for its entry into the war, it is easy to see why many would have felt cheated.37 Italy’s economy was in ruin and as the country did not receive as much support and help in the years following the war, this feeling of failure was only exacerbated, something which directly stimulated the political and social movements that would develop in the years to follow.38

In order to support the war effort, the Italian government had increased the printing of money to fill the demand for arms, but ruined the economy in the process as inflation quickly escalated.39 By the end of 1920, the value of the Italian lira fell to only one-sixth of what it had been prior to the onset of WWI.40 As explained by Spencer Di Scala, between 1919 and 1920 “the state took in 15,207 million lire and spent 23,093 million, and the situation worsened the next year”, substantially reducing the value of the exchange rate and increasing the cost of living.41 During these two years, much of the industry which fueled the war quickly went bankrupt, and unemployment rose to over two million people with the return of veterans looking for work.42 The economic instability of Italy brought with it a vast feeling of uncertainty, something which fueled the development of multiple strikes and protests across the country.43 This atmosphere also created the perfect grounds for fascism to gain more traction, often with the support of ex-soldiers, students, and those who declared themselves pro-war.44 It was during this time that an organization known as Fasci Italiani di Combattimento (The Italian Fighting Leagues) was rising in popularity. The organization was founded by Benito Mussolini in 1919 and its members became known as Fascisti (Fascists). It was directed at war veterans from all political leanings through its pro-militant and extreme nationalist views.45 While in part originally modelled after Mussolini’s own ties to socialism, the party turned towards anti-socialist and anti-communist views after the failed election of 1919, promoting violence and exclusivist affiliations.46 The organization was originally more progressive in its views, with goals such as universal suffrage, eight-hour work days, and a minimum wage.47 However, following the 1919 election and the organization’s failure to elect its members to government, Mussolini abandoned these ideas, and looked instead towards concepts that were less revolutionary and therefore more appealing to the Italian bourgeois.48

In 1914, Mussolini had been a founding member of Fascio d’Azione Rivoluzionaria (Fasces of Revolutionary Action49), a movement mainly active in 1915, which pushed for Italian intervention in the war; a clear departure from his anti-interventionist socialist past.50 While Mussolini was originally a member of the Partito Socialista Italiano (Italian Socialist Party), he was expelled in 1914 due to this stance.51 Many of its members, including Mussolini himself, went on to fight in the war, further developing the movement’s continuity in the postwar era.52 In early 1919, as many began to feel unrest “with peace failing to live up to expectations”, many Italian citizens became embroiled in political violence.53 In March of the same year, Mussolini restructured the Fascio d’Azione Rivoluzionaria into the Fasci Italiani di Combattimento (Italian Fasci of Combat), a decidedly more aggressive organization. Fascism under Mussolini would come to be characterized as a rejection of democracy and liberalism, focused on national unity, aggressive foreign policy, and a desire to restore Italy to its former glory, all of which began to form with this movement.54 Following a rally in which a socialist demonstrator was killed, a large strike was planned for April 15th. Reluctant to allow socialists to occupy Milan, various nationalist groups formed their own demonstration, including Mussolini and his followers.55 In Milan, the local Fasci Italiani di Combattimento had been formed only three weeks prior to the demonstration, yet more than half of its members had served during the war, showing just how malleable soldiers were to the cause.56 In this year, Mussolini also created the Squadre D’Azione, action squads whose members were tasked with helping him defeat his political opponents.57 Though members of the Fasci Italiani di Combattimento were unsuccessful in winning seats during the 1919 Italian election, the organization continued to gain members and Mussolini restyled it into a formal political party known as the Partito Nazionale Fascista58 (National Fascist Party) in 1921. In October of the following year after a coup d’etat known as the Marcia su Roma (March on Rome), Mussolini became Prime Minister when King Victor Emmanuel III, fearing bloodshed at the hands of Mussolini and his followers, appointed him to the role.59 Mussolini ruled Italy as Prime Minister from 1922 until 1925, and was further recognized as Il Duce of Fascism and dictator from 1925 until his death in 1945. This position was one only held by him.60

The rise of political violence within Italy in 1919 was facilitated by the return of veterans home from war. Many soldiers of the Italian Army sought to find a new purpose in society, becoming entangled in various political and activist movements. One such group was the Associazione Nazionale Arditi d’Italia61, formed in Rome in January of 1919, which sought to help these veterans re-enter postwar society with a new political role, as many believed it was owed to them for their service.62 The reorganization of the postwar Arditi can also be traced within a political framework; from their development as assault troops, to immobilized fighters, to disenfranchised veterans. They were seeking their own purpose through various avenues: socialism alongside the Arditi del Popolo, ultranationalism with Gabriele D’Annunzio, or fascism, alongside Benito Mussolini.63 The immediate post-war period marks the moment in which a large number of Arditi were most closely aligned with fascism. Mussolini explicitly directed his political party to veterans, by promoting the use of violence to achieve reward, reclaiming what had been taken from them, and aiming to provide soldiers with proper rewards for the trials they suffered in the war.64 Given the fact that many ex-soldiers at this time were not politically aligned, it made it easy for Mussolini to bring them to the cause.65 Members of the nationalist groups included not only fascists, but futurists, former reserve officers, and ex-Arditi assault troops.66 Historian Mark Jones claims that many of the troops had “psychologically internalized the self-image of their units as the men who fought most violently for Italy’s wartime cause”.67 Italian propaganda during the war supported the idea of an Ardito as being an “Italian ‘warrior’ who defied death just as much he delivered it”, an idea Jones pulls from the work of Giorgio Rochat, something which carried this image forward.68 For Jones, these ex-soldiers sought to reap their rewards through military-style violence, albeit without artillery this time.69 Some former Arditi attempted to organize themselves within their own group outside of the already established A.N.A.I., and were determined to carry on the spirit they exhibited in the war; it was, ultimately, an effort to consolidate their position of importance.70 This choice later allowed them to move away from the rest of the veterans and onto their own political endeavours. Some former Arditi, disagreeing with various policies adopted by the party (especially in response to Italy’s alliance with Germany) would later align themselves with the Arditi del Popolo, an anti-fascist political party, together with other socialist and political groups. However, the majority of Arditi became involved first with the Fasci Italiani di Combattimento and then with Fascism, bringing the corps into the public eye.71 When the Fasci di Combattimento were absorbed into the PNF in 1921, the Squadre, whose members were known as Squadristi, were reorganized and brought under official control.72 This change included the renaming of the squadristi into the Camicie Nere (Blackshirts), as well as the creation of the Milizia Volontaria per la Sicurezza Nazionale73 (The Voluntary Militia for National Security), the paramilitary wing of the PNF, under which the Blackshirts now operated. Due to their command of weaponry during the war and their status as the “daring fighters” of the Italian Army, the Camicie Nere and the MVSN were directly modeled after and influenced by the Arditi.74 Mussolini was also inspired by the uniforms of the Arditi, and he not only dressed his Camicie Nere in the same colour the Arditi wore, but also used the black fez worn by them as part of their uniform.75 The majority of the early Blackshirts were veterans, and a high percentage were formerly Arditi.76 By the end of 1922, many Arditi had officially joined Mussolini and agreed to act as an ‘armed wing of the nascent fascism’77 within the MVSN.78 As a former Ardito, Ceccato was part of – either directly or indirectly – the growing debate on what role the Arditi would play within the newly born Fascist cause. This period of action for the Arditi within their newly developed political role paved the way for the expansion of the Fascist cause within Italy and its notoriously violent authoritarianism.79

When interpreting Ceccato’s letter, it is important to try and recognize the opportunities fascism and Mussolini’s cause offered its followers during this time. The economic, political, and social climate of the years leading up to 1934 left Italians with a lot of uncertainty for the future. Fascist organizations such as the Opera Nazionale Dopolavoro80 (National Afterwork Association) brought Italians together, often offering them job opportunities, camaraderie, and a sense of purpose.81 This is undoubtedly why many, like Ceccato himself, chose to align themselves with the group. However, while Fascism may have created a brotherhood of sorts, the punitive actions directed towards Socialists, Union Representatives, and other minority groups in Italy were violent and completely unjustifiable as responses to the economic hardships they were facing. Fascism would come to be associated with one of the darkest periods of Italian history and persecution, and for good reason. While the Fascists attempted to justify their actions by stating they were necessary to restore law and the economic well-being of the State, the early statistical data collected by Giacomo Matteotti, a socialist deputy who served in the Chamber of Deputies alongside Mussolini and was killed by fascists in 1924, proves this was not the case.82 Matteotti’s 91-page chronicle, published the year after his murder, details countless examples of Fascist violence against Italians, both Socialists and common citizens who did not align with Mussolini’s view for Italy.83 Matteotti himself helped to provide an interpretive frame for assessing the early 1920s in Italy, and more importantly, Mussolini’s consolidation of power following the PNF’s first year in office. While voted into office with the goal of restoring peaceful authority, many felt as though the party was not doing this. Liberals and moderate Fascists believed the party would renounce the use of illegal violence, something which had been plaguing Italy since the end of the war.84 Even following the party’s voting victory, their opponents refused to admit they had legitimately won, and some – like Matteotti – were vocal in their opposition.85 Matteotti spoke to the Chamber on May 30th, 1924, to bring some of the many crimes and “excesses” committed in the name of Fascism to light.86 On June 10th, he was abducted while on a bridge in Rome and murdered by associates of Mussolini.87 Though his body was not discovered for a month, many were confident the Fascists were at fault, something which shocked Mussolini – who thought he could get away with the crime – and caused many to falter in their support of the cause.88 Though Matteotti’s scathing timeline of Fascist violence was published in 1923 and was immediately followed by his suspicious death in 1924, it did little to stop the party’s control of the State. Even with Mussolini’s crimes aired out for all to read, he still escaped retribution. Taking full responsibility for the crimes he both committed and incited – the exact outcome his opponents asked for – he challenged Parliament to persecute him, but with no action taken by King Victor Emmanuel to push Mussolini out89, he carried on to become dictator of the Italian State in 1925.90 Though the grand promises of Fascism and its newly revived State were now possible, the next nine years failed to fully live up to its guarantees. While under Mussolini, the government aimed to make Italy more self-sufficient than ever, decreasing the number of foreign imports and ramping up its own production of materials and resources.91 Promoting the industrial growth of the country allowed the government to better control prices, production, and the allocation of resources more effectively.92 The addition of labour reforms and more welfare programs – presumably the same sort of programs which aided Ceccato and his family – helped ensure more social stability within the country.93 However, with all these improvements came unforeseen problems. Leading up to 1934, the Italian government had amassed significant debt, inflation had increased, and the new economic policies led to an increase in corruption, lack of competition, and inefficiency, all of which would come to plague Italy as it headed into the next war.94 With unemployment rates up –from 300,000 in 1929 to 1 million in 1933 – and manufacturing rates down, many Italians like Ceccato struggled to make ends meet.95 With this struggle came desperation, something that pushed Ceccato to write a letter to the Duce in 1934.

Analyzing the Words of Gregorio Ceccato

Ceccato begins his 1934 letter by addressing Mussolini as “Sua Eccellenza il Capo a Governo Duce del Fascismo Benito Mussolini” (His Excellency the Head of the Government [and] Duce of Fascism), his official title.96 By 1934, fascism had already been an undisputed political player in Italy for fifteen years, and the country had been under a fascist government for over ten years.97 On the first page of the letter, Ceccato offers a glimpse into his life before the war, including his birth on January 2nd of 1898 and his marriage to Angela Della Giustina, a woman he met in Vittorio Veneto while visiting the city as a soldier.98 Though Ceccato does not divulge his experiences on the front lines until later into the letter, he ensures Mussolini is aware of his status from the very first page where he lists himself as being a member of the 8th Artillery.99 In the same section, Ceccato indicates that he and his family have been struggling since 1926, eight years after war’s end (and only four years after the March on Rome).100 We learn that as Ceccato’s brother was injured during the war himself, he received a daily pension of 17 lire, around 510 lire a month, as a form of government aid.101 Though his brother passed away in 1923, he was able to help support Gregorio and the rest of the family from 1918 until eight years after his death, indicating his government aid continued post-mortem. By the time Ceccato composed this draft, three years had passed since this support was cut off and he was then married with five children under the age of twelve: two boys and three girls.102

In order to express his troubles to Mussolini, Ceccato details the various jobs he has held since being released from duty in 1918. Like many soldiers who returned from war, Ceccato found it difficult not only to find a job, but to keep any form of work in the interwar period. After falling into poverty, Ceccato found employment as a salesperson selling silk.103 He was able to keep this job for three years, until the silk market in Italy began to decline and he was let go.104 The rise in foreign silk markets during the 1920s, such as those in Japan and China, caused Italian production to decline heavily as silk coming from the East was cheaper to produce, import, and purchase.105 This was only one of the many industries which unfortunately suffered in the postwar era. Not long after, Ceccato was able to find a job as a carpenter, though having no previous experience working in the field. Unfortunately, this also ended poorly for him, as the factory he worked for went bankrupt a few months later 106. Ceccato remained unemployed for almost an entire year, until he was lucky enough to find work as a manual labourer. For two years, he worked for Giovanni Della Coletta Company creating asphalt.107 Not much information can be found about the company, however an official trademark dated February 4th 1927 attributes the name “silex-bitum” to the resin compound the company used to create asphalt and bitumen.108 The very same compound, which is often used in its powder form in the development of roads, was toxic and posed a danger to Ceccato’s health.109 This forced him to leave the job and once again seek work elsewhere.

While it is not clear exactly how many years Ceccato spent unemployed between 1919 and 1934, when he composed this letter he was still struggling to find employment which could allow him to properly support his family. In 1934, Ceccato had a job as a musician at an Afterwork Club.110 These clubs, called dopolavoro in Italian, were similar to modern day community centers, but during this period they mostly acted also as meeting places for members of the same political affiliation.111 In his writing, Ceccato refers to the location as both Casa del Fascio (House of Fascism) and dopolavoro (afterwork club), naming the location he performs at as Casa del Fascio Arnaldo Mussolini, named in honour of Benito Mussolini’s brother who died of a heart attack in 1931.112 Though here Ceccato appears to use the two terms interchangeably, in reality Casa del Fascio and dopolavoro constituted two separate facets of life in Fascist Italy. Afterwork clubs were controlled by the Opera Nazionale Dopolavoro (The National Afterwork Club), the Italian Fascist leisure and recreational organization founded by Mussolini in 1925. Many of the trade unions under Fascism began to push for their own set of cultural organizations that could uplift the morale of workers, much like the Socialists already had in place by this time.113 The structure of the dopolavoro was similar to that of a YMCA and was originally inherently apolitical, focused not on promoting fascism but rather on the idea of bringing fellow workers together through activities and various sports, though the clubs ultimately did help to increase public support for the party.114 In reality, they were much the opposite of the Casa del Fascio, which were the centre of Fascist affairs in each city. These locations, also referred to as Palazzo del Littorio, acted as the seat of the PNF (National Fascist Party) in cities and towns around Italy during Mussolini’s dictatorship.115 Around 11,000 Case del Fascio were created during the interwar period, with over 5,000 locations being built solely for this purpose rather than simply repurposed from other community offices.116 These buildings could have acted as not only offices for top Fascist leaders, but as meeting places for members of the group within communities. No record of a club matching the name Ceccato provides can be found in Vittorio Veneto or any of the nearby cities, such as Treviso, and this is likely due to a name change or removal of the title following the Second World War and the implementation of various anti-Fascist Italian laws. It is possible the location of the dopolavoro and Casa del Fascio could have been the Comune di Vittorio Veneto, the city hall located in Vittorio Veneto’s main square, Piazza del Popolo. While not able to prove this, many qualities of the building would have made it the perfect location. As the city hall, it makes sense it would have been the seat of the Fascist party within the city during this time, given it was also the seat of the “Podestà di Vittorio Veneto” at the time. In Italy, the podestà was the highest-ranking member of the civil office, holding a role similar to that of a mayor or chief magistrate. From 1931 to 1938, the Podestà di Vittorio Veneto was Giacomo Camillo De Carlo, a prominent member of the National Fascist Party with roles both at the municipal and provincial level.117 In 1923, he even welcomed Benito Mussolini himself to his palace, Palazzo Minucci-De Carlo, in Serravalle, a neighbourhood in Vittorio Veneto only a 5 minute car ride away from city hall.118 As the podestà, De Carlo would have undoubtedly had an office within the building, likely meeting with fellow members of the party within it. A further connection to the PNF can be seen in the Latin inscription seen at the top of the Comune di Vittorio Veneto, which reads “Haec tua domus civis” which translates roughly in Italian to “Questa è la tua casa cittadino” (This is your house[,] citizen). This is however still a hypothesis of the location Ceccato refers to.

Though he held the position of a musician at the dopolavoro, which he seems to imply paid a small wage, Ceccato was unable to find full-time work and take care of his family as he wished. Ceccato explains that though he is included on a “list of poor people who receive help”, likely a form of government financial assistance, both him and his family suffer from hunger.119 Ceccato’s personal feelings on the matter become clear here, as he expresses his fear of what his children’s futures will look like. His devotion to Mussolini’s cause is also illustrated as he describes to the Duce this sentiment, saying:

Se le cose non si cambiano non avrò la gioia di dare alla Patria cara Fascista dei fieri e valorosi soldati (come lo fui io) ma bensì deboli e paurosi.120

(If things do not change I will not have the joy of giving the dear Fascist homeland some proud and valiant soldiers (as I was), but rather weak and fearful ones.)

Ceccato, War Diary, 127.

Though Ceccato finds himself in a period of hardship during this time under Fascist rule, his devotion to the nation and the cause does not seem (at least in literary terms) to diminish. Instead, he looks towards it as the solution to his afflictions.

Further on, Ceccato provides more details about his financial struggles, expressing he is 4,000 lire in debt. A few years prior, when the family was receiving around 510 lire a month from his brother’s pension and Ceccato was able to find steady work, the family’s debt may not have been as crippling, but now it posed a serious risk to the family and their ability to endure:

Mi sento spezzare il cuore ed impaurisco, nel saper la mia famiglia a codesta situazione. Con 4 mila lire di debiti e per conseguenza tutte le porte son chiuse, e più importante il negozio di generi coloniali. Non o più nulla di speranza in questo paese e nel mio nativo121, ma bensì confido in Dio, che Ella Eccellenza Somma Carità e assistenza dei poveri, Voglia darmi una assistenza. Quanto lieto sarei se potessi aver un qualche impiego di qualsiasi specie, pur di veder vivere onestamente la mia famiglia.122

(I feel my heart breaking and I’m frightened knowing that my family is in this situation. With 4,000 lire of debt and consequently all doors are closed, and more importantly [those of] the colonial general store. I have no more hope in this town and in my native one123, but I trust in God that your Excellency’s Supreme Charity and assistance of the poor will provide me with assistance. How happy I would be if I could have some employment of any kind, just to see my family live honestly.)124

Ceccato, War Diary, 127

Ceccato writes this letter to Mussolini as a final resort, his words clearly implying he is beginning to lose faith not only in himself, but in his home of Vittorio Veneto and his birthplace of Asolo. Further, his words can be read as not only referring to Vittorio Veneto, but the country as a whole. Within the section, it appears that Ceccato’s belief was that the Duce could and would assist him in this difficult situation, allowing him to change his life for the better and once again restoring his faith in Italy. While Ceccato uses many lines of his letter to express his devotion to Mussolini’s cause, there is the possibility Ceccato did so for his own gain, feigning devotion to fascism in the hope of receiving a reward. While Ceccato’s remaining family have maintained the belief that Gregorio was not himself a Fascist – or, rather, that the whole family embraced anti-fascist sentiments – this letter in its unexamined form comes across as expressing the words of a believer. However, this is in part refuted by his contradictory phrasing, which implies a clear mistrust in the state; a lack of faith in the Italian Fascist “empire”. The situation Ceccato finds himself in during 1934 as he writes this letter, makes him unable to support the Italian Fascist enterprises, such as the “negozio di generi coloniali” (colonial general stores), something which appears to upset him.125 Colonialism had long been practiced within the Italian Empire prior to the Great War, but with the rise of Mussolini and the resurgence of admiration for the Roman Empire of Antiquity, many colonial goods became prized commodities which not only supported the colonies, but the State as a whole.126 Ceccato appears to express his sadness as not being able to purchase colonial goods for his family, thus supporting the larger Fascist cause. Gregorio states that should Mussolini choose to help the Ceccato family, they could then again support the empire economically, and he could both restore his faith in Italy and allow his children to grow into “fieri e valorosi soldati” (proud and brave soldiers).127 As the letter continues, Ceccato begins to dive deeper into his military experience, signaling an intentional digression from his failing belief and a return to detailing his commitments to Italy. As will be discussed further on, whether Ceccato’s words can be taken for their face value or not, is still up for debate.

From the very start of the letter, Ceccato began to frame his military career. When he describes meeting his wife in Vittorio Veneto, he explains that his presence in the city as a soldier was due to him joining the army there.128 Ceccato states that he was enlisted in the army for two years and five months, beginning in 1917 when he joined the 8th Artillery.129 While the detail provided by Ceccato is not sufficient enough to know for sure the regiment he fought with, it is likely he is referring to the 8th “Pasubio” Land Artillery Regiment. The regiment was created in 1860 and played an instrumental role in the battles for the unification of Italy.130 During the First World War it also played a key role in many of the Northern Italian battles, including the Battle of the Piave River, which Ceccato recounts on pages four and five of his letter, and the Battle of Vittorio Veneto, which ended the war in Italy.131

Gregorio Ceccato’s account of his experience fighting on Mount Grappa, a large mountain just southwest of Vittorio Veneto, accounts for the majority of the letter and makes up its most compelling portion. Though the events of the battle constitute a fairly distant past for Ceccato, his recollection of the events is still vivid and full of detail. Almost seventeen years later, he relates to Mussolini that he often returns back to this moment, signifying it as not only an important milestone in his military career, but of his life as a whole. He begins by detailing his role in the Second Battle of the Piave River, fought between the 15th and the 23rd of June, 1918:

Ricordo spesso il 15 1918 trovandomi sulla vetta del M. Grappa con la 69.sa Batteria d’assedio mortai De Steffani calibro 210 12 Gruppo, che al mattino alle ore 3 inaspettatamente cominciò terribile l’offensiva nemica, con gas asfissianti che portò panico in batteria.132

(I often remember the 15th [June]133 1918 when I found myself on the summit of Mount Grappa with the 69th siege battery of 210 De Steffani caliber 12 group mortars, when at 3 o’clock in the morning unexpectedly began the terrible enemy offensive, with asphyxiating gasses that brought panic to the battery.)

Ceccato, War Diary, 126-127.

Also known as the Battle of the Solstice, the battle was fought between the Austrian and the Italian Armies, both assisted by their allies. It was originally planned by the Austrians as a final offensive to strike the Italian Army, one modelled after the Germans’ Spring Offensive134 to bring about the collapse of the Italian military. Italy was fortunate enough to gain intelligence of the plans for the battle and was able to launch into action half an hour before the Austrians had prepared to attack.135 As I will point out shortly, this is not, however, how Ceccato remembers the onset of the battle.

Accounts of the battle detail the choice made by General Arnaldo Diaz to strike various groups of Austrian troops with artillery before they had the chance to begin their own attack, delaying and stopping their ability to cross the river.136 In the letter, Ceccato expresses his surprise at the start of the battle, which began with the shocking use of “asphyxiating gasses”.137 In the case of Ceccato, the beginning of the battle was not a preplanned start, but rather one that began with an attack by the enemy. While portions of the Italian Army may have had the upper hand at first, Ceccato’s account paints a much different picture of the battle. This perspective may seem incorrect as it deviates from the general narrative, but it also represents a clear example of the disconnect between military personnel like Ceccato, akin to the average fighting soldier, and those in command, such as General Arnaldo Diaz, who directed the line of fighting and would have received the first notice of attack. While Ceccato’s account of the beginning of the battle is not entirely accurate from a historical perspective, it is accurate from a personal one; it represents the chaos of battle and helps to understand the difficulties in planning attacks when the front line was stretched across miles. According to war records, the battle began on the Adriatic Coast, approximately eighty kilometers away from where Ceccato presumably stood (image 10).138 Ceccato describes himself as being placed on the peak of Mount Grappa, accompanied by the “69.sa Batteria d’assedio mortai De Steffani calibro 210 12 Gruppo” (69th siege battery 210 De Steffani caliber 12 group mortars), which appears to have been a division of the 8th Regiment139. Though Ceccato’s use of grammar makes some lines harder to decipher, here he is referring to a unit he names as the 69th Siege Battery, which were in charge of controlling a group of twelve Mortaio140 da 210/8 placed on De Stefano carriages.141 Though the Italian name resembles mortar, these weapons were known as siege howitzers, and are roughly a cross between a cannon and a mortar.142 While Ceccato makes quick work of describing his jump into action and firing of the howitzer, understanding the weapon itself makes the words he writes so much more impressive. The howitzers were large and virtually immobile once placed, yet they were commonly deployed by the Italian during this portion of the war. As the Front Line was static in its position until the Battle of Caporetto – fought between 24 October to 19 November 1917, which resulted in the Italian Army being forced to retreat 150 miles – moving and taking them apart was not necessary, though the howitzers could be transported.143 Following the retreat, however, it became more common for them to be moved around.144 The mortaio of the howitzer, that being the mortar (barrel) in which the ammunition was loaded and discharged from, weighed around 2100 kilograms on its own.145 The affusto, translating to gun carriage, weighed an additional 8830 kilograms, bringing the total weight of the weapon Ceccato fired from to 10,930 kilograms.146 While written like this the numbers do not mean much for those unfamiliar with this type of weaponry, the weight of the weapon once assembled for those using them would have been equivalent to the gross vehicle weight of a 2021 Chevrolet Silverado 6500, the largest personal truck Chevy sells.147 Of course, there was no single soldier who could carry or move this weapon alone, nor would the entire group have been able to. Given Ceccato and his battery were using multiple of these howitzers, as well as the fact that they were fighting in the harsh environment of the Italian Alps, they relied on trollies and tracks to transport the gun and its components around.148 This would have involved both taking apart and putting back together the gun when needed, undoubtedly something that must have been a group effort. Transporting these weapons also would have included moving the ammunition supply and shells to be used in the gun. These weighed anywhere from 61 to 103 kilograms each, depending on which type was used. While Ceccato expresses more of a knowledge on aiming the guns than loading them, it is likely he would have performed this action at times too. Based on notes he wrote while in action, Ceccato seems to have been very familiar with the function of not only the gun, but the ammo as well. It is unclear whether Ceccato was formally taught how to use the weapon or simply learned while in the field, but what is clear is his true affinity for learning how to best position and use not only this howitzer, but every type of weapon he had at his disposal.

In his memorialization of the Battle of the Solstice, Ceccato moves on to describing to Mussolini his role, clearly outlining not only his skill in using this weaponry, but also his military valour in action.149 At the onset of the battle, Ceccato describes himself as immediately taking his assigned position, jumping straight into battle without even “wasting time with the [gas] mask on my face”.150 In this section, Ceccato alludes to his relevant role in the battle, describing himself as being positioned by his corporal, yet taking the time to count those who were fighting alongside him. Taking note of nine of his fellow soldiers in line with him, Ceccato describes his realization that the sergeant and one soldier were missing when the offensive began.151 Putting his own life in danger, Ceccato pushed through the fighting – even being buried by a grenade – in order to find them.152 While he was able to find the sergeant, whom Ceccato seems to allude was not missing but rather just in another place, he had to look for his fellow soldier more thoroughly. After twenty-nine shots had been fired, Ceccato found his fellow comrade, and described how he had to shake him out of shock and then return him to their starting position.153 For this, Ceccato writes to Mussolini that he received the Cross of Merit as a reward, but his positive reward for his valour does not appear to count for much afterwards.

Ceccato continues by describing his return to his gun around 3:30am, a half hour after the battle had begun. While this paragraph, like many others within his diary, does not cleanly translate into English (nor does it entirely make sense in its original Italian), Ceccato appears to describe his positioning of the third and fourth howitzers in the line. Within the letter Ceccato describes himself as being a “puntatore” (gunlayer).154 Though this term is not commonly used as a formal position title in English, it is easy here to understand what he means by it. Ceccato appears to have been tasked with aiming the guns to be fired, something supported by the photo of the gun trajectory above. At 3:30am, he recalls having to position the guns in what he calls a “falso scopo” (false aim).155 This term was used by Italian artillery as a way to describe the positioning of these guns. As the projectiles of the mortars were known for ricocheting, they would ‘falsely’ aim the weapons in order to achieve the desired enemy target, protecting themselves from friendly fire.156 Given the time of the battle and the battery’s position on Mount Grappa, it would have been impossible not only to see the enemy in the dark, but also to accurately plan the shells’ trajectory, thus it is easy to assume they would have aimed at what they knew, and hoped for the best. Placed in what he considered to be a very dangerous position and being forced to light the guns, Ceccato hints at the fact that he quickly got over any fear and lit them.157 Unfortunately for him and the rest of the battery, Ceccato writes that they were soon destroyed “dal scoppio di un 420 nemico” (by the explosion of an enemy 420).158 Here he is likely referring to the “Big Bertha”; a 420-millimeter howitzer gun which was used by the German and Austro-Hungarian armies during WWI.159 When first used in 1914, they were the most powerful artillery weapons in any of the fighting armies, being able to fire projectiles weighing up to 817 kilograms up to 9 kilometers away.160 While the Mortaio da 210/8 was powerful, the bore of the barrel only measured 210 millimeters across, with the maximum weighted ammo only reaching 103 kilograms, traveling a maximum of 8 kilometers of distance.161 The most commonly used shells in these guns had delayed action fuses, meaning they could explode after penetrating up to 12 meters of ground on enemy territory.162 Ceccato describes having to move to a safe distance after lighting the gun, in order to escape the explosion of one of these unscathed; this must have involved quick movements and optimal positioning within the mountain.

As with his previous recollection of his fortitude, Ceccato never ceases to embody the Ardito during this battle. Following the destruction of their weapons, Ceccato describes the actions of a fellow unnamed corporal “che si mise a piangere disperatamente” (who began to cry desperately).163 While Ceccato does not attempt to explain why the corporal behaves in this way, it is likely he was either shell shocked or scared by the destruction happening so close by. The captain in command, who is also unnamed, is described as having threatened the desperate corporal twice with a revolver, but even that could not change his mind.164 Ceccato explains to Mussolini that he ran to the corporal’s side, seeing the captain holding a revolver to his head and threatening to kill him if he did not retake his position in the fighting.165 Since the corporal claimed to be happier to die on the spot than return to his firing position, the Captain pulled the trigger, only missing because another sergeant touched his elbow to deviate the bullet. While this account paints a clear picture of the tensions on the front line, it also helps to see Ceccato as not only a fearless fighter, but a level-headed thinker. While the Captain was undoubtedly angry at the other sergeants’ intrusion, Ceccato describes himself as having intervened to save him:

Voltosi contro il sergente minaccioso, ma io in quella mi feci arditamente avanti e dissi: Signor Capitano, ne muoiono abbastanza, senza che uccida Lei per cose da poter rimediare. Ebbene vai te.166

(He [the Captain] turned threateningly towards the sergeant, but I boldly stepped forward and said: “Captain, enough people are dying without you killing them for things that can be remedied.” [To which the Captain replies:] “Well, you go167.”)

Ceccato, War Diary, 124.

Upon receiving this stern demand, Ceccato writes that he took no moment to fear any retribution for his speaking out, instead rushed to his position, lighting the fuse on another (unharmed) gun, and sought shelter underneath a rock. While his position at this time is not entirely clear, Ceccato seems to imply he was perched on a cliffside, with some sort of overhang above. In the next few lines, Ceccato explains to Mussolini that it was at this very moment, while he was seeking shelter, that an Italian 240mm mortar168 placed above him exploded, smashing his own howitzer and trapping him “sotto il vulcano di macerie” (under the volcano of rubble).169 Ceccato describes his Captain as calling out to him, pulling his hair in frustration and despair, and being shocked at his emergence from the rubble unscathed. Seeing this, the captain promised to give Ceccato a prize, signifying yet another moment in which his courage should have been rewarded.

While we are unable to verify the events Ceccato describes, within his diary he paints himself to be the true embodiment of an Ardito. Ceccato’s performance during this battle is one of no fear; that of a strong-willed soldier, eager to fight for his country, regardless of the fact he might die. This is of course the way he would want to be perceived by Mussolini as the intended reader, but Ceccato’s recollection of certain minute details, such as the precise number of twenty-nine shots having been fired while he seeked out his fellow soldier, make it hard to doubt the authenticity of his narrative. While his true devotion to Mussolini’s cause is far less convincing, his disappointment and anger towards the state of Italy by 1934 makes sense in light of the debilitating events he describes in this portion of the letter. While he would obviously want Mussolini to believe he is deserving of his requested help, for Ceccato this fragment of his life is the main and ultimate reason he deserves the Duce’s attention. For him, this is not the moment he needs pity, but rather appreciation and thanks for all he did for his country.

As Ceccato begins to wrap up the letter, he aims to drive the point of his writing home. Describing the following few days, months, and years since the events he detailed, Ceccato illustrates key examples of how he has been let down by his country. Naming a lieutenant Paiola Bolognese170, Ceccato writes to Mussolini that following the two acts of valour he performed during the Battle of the Solstice, the lieutenant told Ceccato he would receive not only a silver medal for his merit, but also a promotion to the role of sergeant.171 This is not however, how the subsequent events played out:

Passato circa un mese con meraviglia e sdegno fui nominato dal maggiore Righi comandante il gruppo, primo ardito della batteria e nulla più. A rapporto, che fui mi disse: Voi eravate in obbligo di fare quanto avete fatto, perché avete difeso realmente i vostri beni la casa paterna, cioè la famiglia.172

(After around a month, with amazement and indignation I was appointed by Major Righi as commander of the group, first Ardito of the battery and nothing more. When I was summoned, I was told: You were under obligation to do what you have done, because you have really defended your possessions, the paternal house, that is, your family.)

Ceccato, War Diary, 122-123.