by Sharon Findlay

Lì [alla stazione del treno a Toronto] ho trovato il mio fidanzato che è venuto a prendermi con un altro amico perché lui non aveva la macchina e allora siamo arrivati a Guelph. Tutto bene, ci hanno accolto bene ma per me era tutto nuovo, mi trovavo persa.

~B. Santi, 2020

There [at the train station in Toronto] I found my fiancée who came to pick me up with another friend because he didn’t have a car and then we arrived in Guelph. All was well, they welcomed us well, but for me, it was all new, I felt completely lost.

Table of Contents

Introduction

Giving Birth: Italian-Canadian Migration and Motherhood

As a nation of immigrants, migration to Canada is a fundamental feature of the tapestry that constitutes our society and cultural identity. A variety of forces have impelled people from all corners of the globe to transition to this country, and then bravely face and surmount the cultural and linguistic barriers that confronted them. Italians are among the earliest Europeans to settle in Canada, dating back to John Cabot (AKA Giovanni Caboto) in 1497. Missionaries and mercenaries began settling in the centuries that followed. Two subsequent waves of emigration occurred the first beginning the 1880’s to the 1920s, during Fascism, emigration paused until the decades following the World War Two (WWII).1 Italians emigrated in massive numbers from their homeland by the millions to countries around the world as well as to other European nations, Great Britain, Australia, Latin America and North America. The main reason for this exodus was to escape poverty primarily in the southern and north-eastern regions of the county.

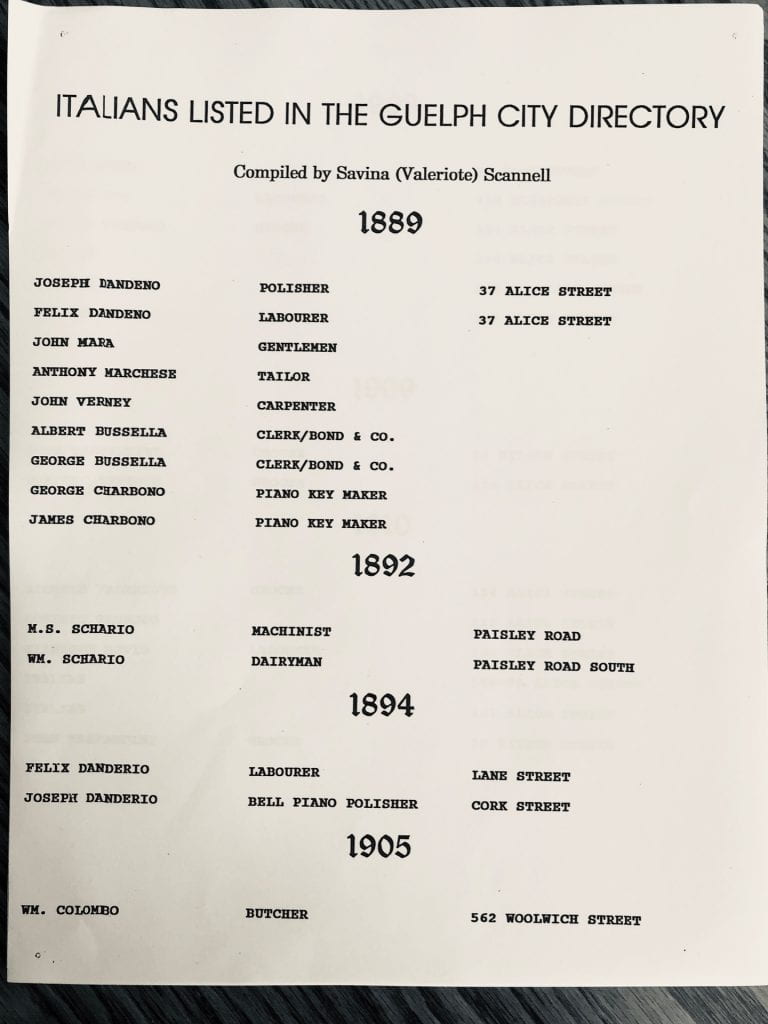

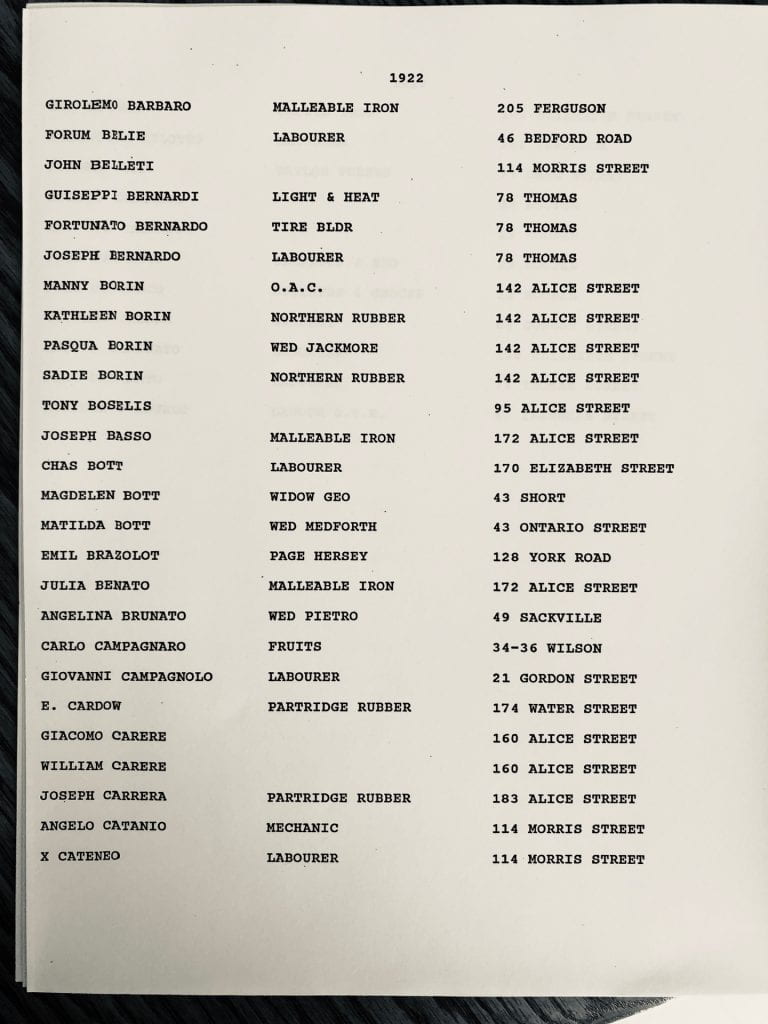

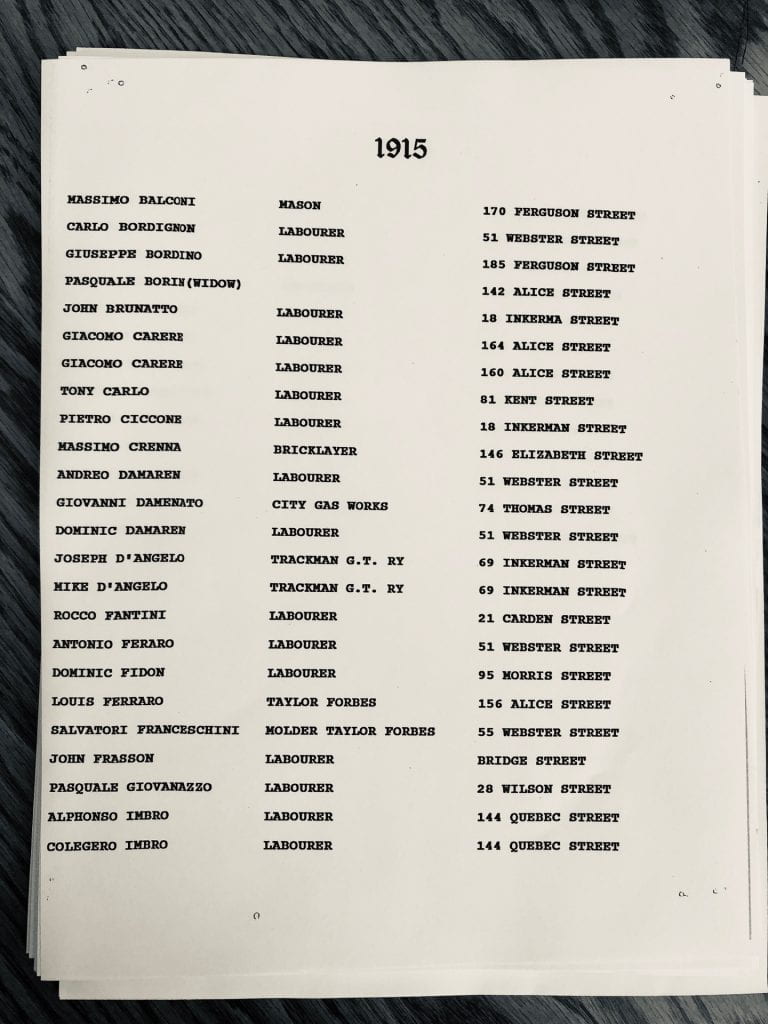

In rural farming communities, there were few prospects for work and advancement. Immigration meant the possibility of work and homeownership, and many leapt at the opportunity. Some immigrated intending to put down roots in their new community while many others, sojourners, came temporarily. In fact, between 1870 and 1970, Italy exported approximately twenty million people, which nearly equalled the number who stayed behind (Gabaccia, Italian History 45) Around half of them would return after seeking their fortunes abroad. At the same time, the rest would form communities in the diaspora, “Little Italy’s” around the globe in which Italian immigrants sought to maintain the continuity of precious cultural traditions, community and kinship ties. Canada represented a major destination for Italian migrants and sojourners. Italian communities and neighbourhoods sprang up in nearly every city from coast to coast. Italians, from 1889 to present have migrated in waves. Many Italians immigrated to the town of Guelph Ontario, just West of Toronto and settled in an area commonly referred to as “The Ward” (and also called St. Patrick’s Ward), which has become well known for its Italian population (Crowley).

“[The Ward] has served for a century and a half as one of the City’s foremost meeting places: between humanity and geography; between people and business; and between peoples of diverse cultural backgrounds and religions. Ward One was called East Ward and St. Patrick’s Ward at various times, though the middle of the 20th century it became known as “The Ward” largely as a result of its Italian population” (Crowley).

According to Dr. Terry Crowley of the Guelph Historical Society, Guelph’s Italian community immigrated primarily, though not exclusively, from two main regions, Veneto (Treviso) region in the north and also from southern Calabria, (San Giorgio Morgeto). This is an essential context as Italy is regionally distinctive, and cultural customs vary significantly from one area to the next. Immigrants from both regions typically came from rural backgrounds with a strong agricultural ethos. The contribution of Italians to Guelph as a whole was expressed in 2011 in the Guelph Mercury: “I think Guelph is wonderful microcosm because of the large Italian population,” said Adriano Gabriel Niccoli, the honorary vice-consul of Italy. He said that with Italian people’s value system and hard work “they really have rewritten the history of Guelph” (Seto)

Although the community is comparatively smaller than other “Little Italys” in Toronto, Ottawa or Montreal, for example, today, the Guelph Italian community stands out as an exemplary success story of immigration, community building and prosperity. Not only in their own right, as successful entrepreneurs, philanthropists and political leaders, but because of their distinctive approach to integration. From the origins of their migratory movement, Guelph Italians had an unspoken mandate to collaborate with, include, and assist migrants from many other cultural backgrounds and communities. Guelph’s Italian population is well recognized as having contributed significantly to the formation of the city, helping newcomers and developing festivals and team activities that reached beyond their ethnic and cultural divisions to unite the whole city. The Guelph Italians created soccer teams, events, public statues and drove various initiatives that are prized today and furthermore, many immigrants and their descendants became pillars of the community such as Frank Valeriote, who served as a Liberal M.P. for several terms. It may be that the relatively small size of the Guelph Italian community contributed to the integration and achievements of this specific population of Italians in the diaspora.

The oral narratives of Italian-Canadians, have been collected by the university of Guelph since 2015, and offer a study in memory and migration in Guelph-Wellington. Early results of this exploration indicate that the process of outlining this group’s account also uncovers how individual relationships to memory and cultural heritage play a crucial role in defining one’s place in the present and support a positive approach to cultural integration. It is increasingly evident that the implications of this unique narrative extend far beyond the preservation of the particular history of Guelph-Italians but extends to the whole multi-ethnic and multicultural community of Guelph, and across multiple generations.

While ethnographic studies and historical accounts of Italian-Canadian exist, such as Nicholas De Maria Harney, and Franca Iacovetta’s seminal scholarly contributions, there is not much available that provides insight into the domestic sphere of Italian immigrant homes and still less about the perspectives of women and mothers.

The perspective of Italian immigrant women and mothers is a complex and yet shared experience that remains largely unexplored in sufficient depth. As Franca Iacovetta says:

For thousands of female newcomers, resettlement in Canada meant being relegated to the lowest-paid sectors of the female job ‘ghetto’ domestic service and low-skilled factory positions and thus taking on the ‘dirty’ jobs that Canadian women shunned. In addition, most of the recollections of immigrant women contain painful stories of prejudice. The fierce taunts of intolerant neighbours and passersby, or the harsh, even cruel, criticisms of an angry employer, harried doctor, or frustrated government worker surface in many such recollections. It would nevertheless be misleading to think of immigrant women exclusively as passive victims, to assume that they led completely isolated lives or that their presence never made any difference to the people they encountered or the places they inhabited. (Iacovetta, “Remaking Their Lives” 137)

This Major Research Paper (MRP) does not attempt to provide a comprehensive response to this deficiency; however, it seeks to gain insight from a selection of six Italian immigrant women’s personal narratives that explores how they remember immigration, which was often immediately followed by first-time motherhood. The challenges presented by significant life transitions, such as immigrating, can be compounded when added to the equation of entering motherhood without the network of support upon which they relied back in Italy as well as culture shock and language barriers that inhibited communication. One woman, Bruna Santi, interviewed for this project, relates the experience of giving birth in a hospital where she could not communicate with doctors or nurses in her native language. She remembers this experience as stressful and frightening; this study will discuss – among other things – how she passed that memory on to her daughter in vivid detail, and how the daughter incorporated her mother’s experience as a postmemory.

In 2015, the Guelph Italian Heritage Project (IHP)2 was established,3 to collect and preserve the oral history narratives of Italian immigrants to the Guelph-Wellington area (and beyond). Through the ongoing IHP project, it became evident that the domestic sphere of women, and childbirth, had not been previously explored and that the views and memories held by women migrants were vastly different from their male counterparts. This emerging distinction between the reported life experiences of men and women led to the conception of this MRP.

Ontario has long been the most popular provincial destination for newcomers entering Canada, and, certainly, the pattern continued during the post-1945 era. Between 1946 and 1965, more than half of Canada’s two million immigrant arrivals chose Ontario. Among the adults, probably close to half of the Ontario-bound newcomers were women. Most entered the country in what for women was the usual way, through the family classification scheme – that is, they were sponsored by fathers or husbands. Others came as contract workers destined for placements in domestic service, the needle trades, and other industries where Canadian employers and officials had deemed there were acute labour shortages. Only a minority came as independent immigrants approved for admission on the grounds that they possessed skills or a professional expertise highly desired by Canada. (Iacovetta 138)

The Giving Birth project seeks to illuminate some of these stories and to achieve a deeper understanding of what it was like to begin a family as a new Italian immigrant in Guelph. The next section will outline the methodological approaches adopted to discuss and analyze the individual interviews. The interviews themselves are described and quoted in detail and examined using the frameworks of oral history and memory studies. The description of each interview endeavours as much as possible to follow the original structure without altering its sequence and thereby the importance placed on various aspects of the narrative by the subjects themselves. The selection of photographs included both illustrate this study and demonstrate how these women’s memories interact with the images that portray various stages of their journeys.4

Methodological Approaches: Oral History and Memory

Methodological Approaches

Literature on American-Italian women can prove instructive as well as provide a basis for exploring some experiences and cultural interactions of Italians moving into a primarily anglophone English-speaking country. Donna Gabaccia explains how, surveys and studies of Italian-American literature– from scholarly reviews to more popular accounts – have often failed to incorporate women’s experiences extensively. (Gabaccia, “ItalianAmerican Women” 38) The Giving Birth project relies primarily on the methodologies of oral history and memory studies to explore Guelph’s Italian immigrant mothers’ experiences. Through the collection and interpretation of firsthand testimonies, the Giving Birth project asks how these individuals remember the experiences of motherhood. Additionally, it inquires into how giving birth in Canada impacts, if at all, each participant’s sense of cultural identity and home.

Immigration, integration and assimilation can look quite different in the United States and Canada due to many factors, including historical and cultural aspects, and government regulations. A comparative study would further illuminate these differences; however, in this instance, such examples serve solely as models and reference points when similar scenarios are described in the interviews. As Donna Gabaccia so eloquently states:

Women helped make ethnicity an important part of each family’s private “little tradition” and, thus, ultimately, a component of individual identity into the second and third generations. Italian women’s kinship work, and their influence over their daughters, became increasingly important in the creation and maintenance of ethnicity as the (predominantly male) ethnic institutions of the immigrant generation waned in the twentieth century. Perhaps that is why, today, women of the third and subsequent generations are more likely than men to believe that ethnicity is a major influence on people’s lives (Gabaccia 46).

In Canada, as in other counties, such as the United States, Ireland or Australia, Italian populations established unique cultural identities. Women played a crucial and determining role in how the kinship networks developed to support and maintain the Italian culture in all of these communities spread far and wide across the globe. Therefore, it is puzzling that more studies on domesticity and motherhood in Italian migration do not exist. A survey of related studies, such as De Tona, Miller, Gabbaccia and Iacovetta, can illuminate similarities and differences of the Italian diasporic experience around the world to the Italian women in Guelph who participated in this project; Bruna Santi, Lorena Pellizzari, Iole Cazzola, Lidia Marcato, Amabile Lovadina, and Livia Tonin.

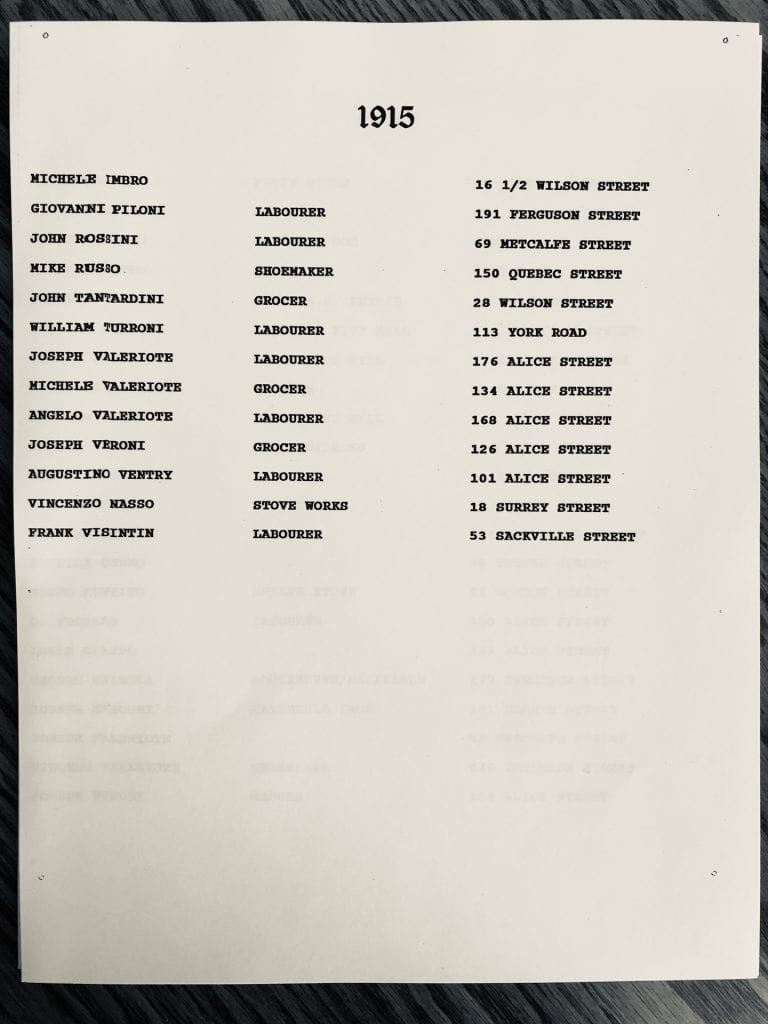

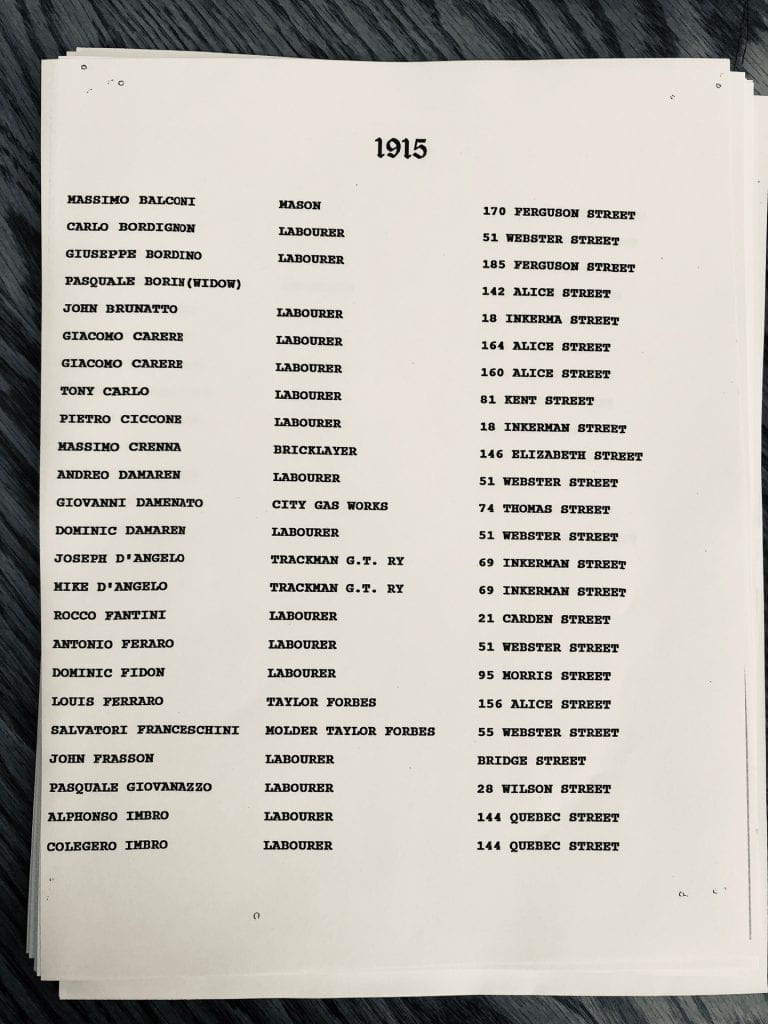

This MRP focuses mainly on the post-war period of the 1950s and ’60s when so many Italians made the tough decision to move to a foreign land to begin a new and unimaginable life. Extreme poverty and lack of economic opportunities motivated millions of Italian men and women to make this journey. Chain migration occurred when immigrants moved to locations where relatives had already immigrated and established themselves to some extent. In many cases, young men would immigrate to seek their fortunes before returning to Italy to get married or by sending their girlfriends to come over and marry immediately. Women rarely immigrated alone and unattached to a male relative or fiancé. Giving Birth explores how this transition and the raising of a family in Canada is remembered and how it has shaped the personal and social identity of the women interviewed. A cursory glance at archives of Italian immigrants dating back to 1889 reveals that men and their professions and addresses were recorded in the immigration forms while women were often listed as wedded to a particular man or not identified at all.5

Memory is the key to identity; how we remember, why we remember, and the story we tell about our experiences is how we contextualize and generate meaning out of the events of our lives. memory studies research has laid a map of how memory, mutable and fallible, interacts with the present and the future. Oral history provides the mechanism for investigating nuanced layers of individual experience while offering researchers a grounded methodological framework to reveal the intricacies of how we remember. In combination, memory studies and oral history can validate, preserve and include previously unheard perspectives, such as the marginalized, into the historical record to broaden our understanding of what it was like to live through specific stages of human history such as the post-war period which was so instrumental in mobilizing a mass exodus of Italians around the world. This research seeks to preserve and illuminate the collective perspectives of life for Italian-Canadian mothers and how giving birth in Canada may have impacted their personal sense of identity. The Giving Birth project represents a tiny sample of participants; however, in general, oral history projects endeavour to collect and record the voices of as many people as possible before it is too late.

Oral History

Oral history is the work of collecting historical information through personal interviews. It is a method of research, the act of recording, the record produced, and the researcher’s analysis of the record. It has been described as a theory, a method, a process, a technique, a tool, and a genre. Knowledge gathered in this way is unique as it relies on the personal experience of the subject expressed in an interview. Oral history is fluid, reflexive, evolving; it is simultaneously a deliberate strategic process that is spontaneously generated in the moment of the interview and a concrete artifact. Oral history is rooted in facts and dates but allows for creative interpretation and meaningful consideration in dialogue with the interviewee, and the his/her past, with the contextual elements that frame a person’s memory of places and events. Oral history is a research methodology but also, according to Alessandro Portelli, an art form. It is the collection of narratives but also the recording and transcript – the crystallized form of the interview that is captured and subject to ongoing analysis. Oral History is a work of intricate communication and relationships across time and space.

The term “oral history” encompasses many aspects of an approach to the past that is human-centred and able to incorporate multiple layers and perspectives by focussing on the perceptions of individuals. The Giving Birth project which touches upon highly sensitive and even culturally taboo subjects, and an oral history approach seemed the best way to access information and gain insight into a relatively unknown territory. Its methods allow the researcher to enter the world of the interviewee and to glimpse into the reality of people whose voices would otherwise have been lost. It facilitates the reflexive exploration in dialogue, of specific events and their meaning in the narrative of the subject’s life.

As a practice, oral history has become increasingly sophisticated in its approach as an interpretative framework and theoretical discipline. A well-established field of inquiry, oral history is cross-disciplinary, adaptable, and frequently used in community enterprises, social, historical, heritage, legal, healthcare and psychology studies, which sometimes rely on oral history methods as investigative tool of inquiry. It thus benefits from the expertise of practitioners from a wide variety of backgrounds. Collecting narratives and recording them is a methodology used in many social science disciplines. However, what distinguishes it from other types of participant-involved research is that oral history must engage with the past. Different methodologies, such as participant observation, often incorporate interviews or first-person testimony into research, but these do not necessarily engage with the past. Oral history refers specifically to remembered events in the interviewee’s life and not, for instance, to oral tradition or information over a generation old that predates the narrator’s life.

There is a well-defined scope that distinguishes this approach from other forms of testimony and specific elements that constitute oral history; however, the interview itself is often open-ended, can go off-script even when it conforms to a framework established by the researcher. Oral history work is complex, nuanced and demands rigorous reflexivity and attention to detail by the researcher employing this method. Precise definitions of the distinct aspects of oral history are necessary for accuracy in a field that can touch upon intimate details of a person’s life. Well established experts in oral history such as Lynn Abrams, Alessandro Portelli, and Luisa Del Giudice provide the foundational theory to aid in the use and application of oral history as an interpretive framework. Broadly, oral history refers to two main aspects – the practice of conducting the interview and the resulting record of the interview. Abrams further expands this to include four separate elements: the original interview, the recorded version of the interview, the written transcript and the interpretation. (Abrams 9) These four aspects form a chain of integral components that are distinct and yet dependent upon one another.

The oral history interview is conversational and different from other historical sources because its nature is dialogic, relational, discursive and even creative. The audio or audiovisual recording and transcript are tangible manifestations of a conversation captured and concretized. Also, as people describe their past, they reveal information about their present self. The interview is the space in which the subject constructs and reconstructs him/herself through narrative. The personal experience of the individual is necessarily embedded in a broader social and cultural context.

Portelli describes his approach as he attempts to “Convey the sense of fluidity, of unfinishedness, of an inexhaustible work in progress, which is inherent to the fascination and frustration of oral history – floating as it does in time between the present and an ever-changing past, oscillating in the dialogue between the narrator and the interviewer, and melting and coalescing in the no-mans-land from orality to writing and back.” (Portelli, Luigi Trastulli vii). 6 was this serious, I would have told you the real story!”] For Portelli, oral history is not just a research methodology but a poetic art form, a dance of relationships that flow across time and culture, and through communities. Practice and theory are entwined in the interpretation which strives for comprehension, not only of what was said but how and why (Abrams 1).

While oral history relies on an individual’s recollection of fragments of experience that are woven into a cohesive story, memory is multidimensional and exists within concentric spheres of experience, family, community and public representations and retellings that affect one’s perspective. The mutability of memory does not detract from its value in oral history research; instead, memory reveals the process of both the internal and external influences on its construction. Oral history exposes the relationships between what, how, and why we remember experiences as well as how factors such as age, sex, trauma can inform reconstruction and understanding of events: “Oral sources tell us not just what people did but what they wanted to do, what they believed they were doing, and what they now think they did.” (Portelli 50).

Oral history recognizes memory as an active ongoing process through the event of the interview. The memory is told and created in the moment that it is spoken. It is mediated by the present, by the questions, by the relationship with the interviewer and the context of cues, photographs, and family memorabilia.

Memory is fallible and fluid, revealing more about where a person is than where she/he has been. It is continuously updated as it is retold and develops in the context of relations to individuals in the narrative, to the past, to those present, to the cultural context and importantly, to the researcher asking the questions. Oral history is fundamental to understanding the content of what is being shared. This approach, when combined with memory studies, forms a combination of strategies that work in tandem to address, collect and interpret the interviews.

A Cautionary Tale and the Potential Pitfalls of Conducting Oral History

Oral history plays a critical role in women’s history, creating a space for voices that have long been silent in a history largely written by men. (Coppola 56)

Participants in the Giving Birth project were given a waiver to sign in print, in English and Italian, which contained information about the project. They were also not obligated to answer any question and were absolutely free to share whatever they wished and no more. The Giving Birth project has Research Ethics Board (REB) clearance, and every participant was informed of her right to withdraw at any time or retract any statement. This procedure is critical as oral historians with the best intentions have, at times, encountered unexpected misunderstandings because these details were not explicitly explained to the subject of research or had been – at times – misunderstood. Marie Saccomondo Coppola provides just such an example that serves as a cautionary tale. In fact, this project is indebted to her insight as her candid essay informed and demonstrated potential perils and pitfalls of oral history research.

Coppola details the oral history project she did with her 83-year-old aunt Rosina in Sicily for her Ph.D. dissertation. She tape-recorded the interview, transcribed and analyzed the narrative, which formed the substance of her thesis in 1998. Upon completion, she presented the finished product to the aunt proudly, assuming that having given her aunt a voice and agency by immortalizing her lived experience, her work represented an invaluable gift to her venerated relative. However, when presented with the final work, instead of feeling validated, her aunt responded with anger and accused her niece of betrayal and humiliation. This was not a passing storm, and she ultimately died without ever forgiving her niece. Coppola’s intention, in addition to applying theory to her personal life, was to ennoble her aunt’s personal narrative, but instead, she inadvertently left her feeling exposed and violated. Even though Rosina knew she was being recorded, she had misunderstood or simply not realized what was going to be in print.

In the original interview with Rosina, Coppola felt secure in the knowledge that she was giving her aunt a validating opportunity to express what she had experienced and accomplished. In their conversation, they covered several key moments such as the deaths of family members and her aunt’s early married life, which she described as “Una Vita Sacrificata” (A Life Sacrificed) This phrase was also featured as a chapter heading in the final manuscript. Her aunt had not realized that those words would be published.

Coppola’s aunt could not read English, and neither could the other family members who were equally upset but did not have difficulty understanding the chapter heading “Una Vita Sacrificata;” it was probably that phrase that fueled their outrage and indignation. Coppola’s male cousin later revealed that all of her aunt’s five sons had been angry at their mother for sharing personal details about the family. The expression would be particularly triggering as it seems to imply that their mother had sacrificed her life, or led a miserable existence, suffered or struggled and presumably was not provided for by her male family members. They were not comfortable with intimate details of their life or their mother’s life revealed publicly. In her brave unpacking of how this unfortunate experience unfolded, Coppola identifies cultural sensitivities and taboos, reflexively exploring subsequent interactions with her cousins in the years afterwards. Many of the themes identified by Coppola are touchy subjects that correspond with Miller and De Tona’s studies in similar family contexts. Coppola’s fieldwork in Sicily revealed deep distrust and fear of outsiders, easily identifiable through their language and lack of dialect or native accent. Within that milieu, women would commiserate or share with other “safe women” – how her aunt had considered her niece until the publication of the thesis, after which she disowned her completely. Coppola explains that the men care little for “women’s talk” taking place between family members and close friends but had a huge problem with having those words committed to paper. A proper Italian or Sicilian bears her burdens stoically and does not complain to the men and especially not to outsiders. Coppola observes that “In painting my aunt’s picture of poverty, I gave away family secrets in detail, that is, what went on behind closed doors.” (Coppola 62)

Coppola compares the lives of her mother (who immigrated to the USA) and her aunt Rosina (who remained in Italy). Her mother worked outside the home while her aunt, a Sicilian woman, never did. While her mother’s life is a compelling rags-to-riches scenario in which she triumphs, her aunt was clearly ashamed of her early poverty. Even though Rosina received more formal education than her mother, she looked down upon women or families with children who were forced to work outside the home. In retrospect, Coppola realized that her aunt and cousins did not understand that they were recorded, and their words would be committed to paper. She could have possibly provided them with a draft prior to publication or asked them to sign consent forms, an act which may have alienated them in the first place. This essay is a cautionary tale as well as a sample of how oral history projects have evolved to avoid such pitfalls. Oral history studies provide a means of gaining insight and preserving knowledge. However, it must be applied carefully, with sensitivity to the participant’s rights and the researcher; a clearly articulated waiver that explicitly explains the scope of the project and the rights of the interviewee to withdraw is crucial to avoiding future complications and reducing the risk of misunderstandings. Unfortunately, in some cases, the bureaucracy and officiality of signing consent forms can feel daunting and scary to potential participants, especially if they are elderly. This likely contributed to the decision of one woman who declined participation in the Giving Birth project at the last minute.

Memory

Giving Birth, which focuses on Italian-Canadian women in Guelph and their experiences of motherhood as immigrant women through oral history interviews, necessarily explores intimate memories, postmemories and possibly reconstructed memories, as in the case of some participants who downplayed the extent of some of the hardships they encountered. While oral history is fundamental, to understand fully the content of what was being shared, this approach is supported by significant research in memory studies to form a combination of theoretical approaches that work in tandem to collect and interpret the narratives gleaned from the interviews. Abrahams observes how “Memory with all its imperfection, mutability and transience is at the heart of our practice and analysis. We want to know why people remember or forget things, the warping and mistakes they make, and ask ‘why'” (23). Memory is imperfect, but its imperfections are useful in revealing layers of complexity. Individual memories are reconstructed to align with each respondent’s worldview, articulating the past through the lens of the present.

Key Terms

Before addressing the interviews, it is essential to discuss a few key terms and concepts. Several foundational thinkers have established this theoretical approach over the twentieth century, and their work is the edifice upon which subsequent theories of memory studies have been built.

Collective Memory and Communicative Memory

“In each epoch memory reconstructs an image of the past that is in accord with the predominant thoughts of the society.” (Halbwachs)

Maurice Halbwachs, a sociologist, first articulates the concept of Collective Memory, the shared memories of a particular society or group which he distinguishes from what he called Communicative/Everyday Memory, which denotes the memories of an individual. Halbwachs’ Communicative Memory is socially mediated and relates to a group, sharing a temporality of only a few generations or 80-100 years. In other words, Communicative Memory has proximity to the everyday while Cultural Memory has a distance from the everyday and encompasses memory (past), culture and group (society).

Cultural memory is a form of collective memory, in the sense that it is shared by a number of people and that it conveys to these people a collective, that is, cultural identity. Halbwachs, however, the inventor of the term “collective memory,” was careful to keep his concept of collective memory apart from the realm of traditions, transmissions, and transferences which we propose to subsume under the term “cultural memory.” We preserve Halbwachs distinction by breaking his concept of collective memory into “communicative” and “cultural memory,” but we insist on including the cultural sphere, which he excluded in the study of memory. We are, therefore, not arguing for replacing his idea of “collective memory” with “cultural memory”; rather, we distinguish between both forms as two different modi memorandi, ways of remembering. (Assmann, Jan)

Building on the groundwork laid by Halbwachs, Jan Assmann, a classical archeologist and major contributor to memory studies, elaborates on the theory of shared memory by asserting that Cultural Memory, is a means of maintaining the nature and shared unity of a group consistently through generations. However, Assmann distinguishes Cultural Memory from Halbwachs definition of both Communicative/Everyday Memory and Collective Memory. Assmann’s thesis contradicts Halbwach’s assertions that Collective Memory disappears after its crystallization into texts, rites, monuments, cities, etc. rather Cultural Memory is something from which groups derive formative and normative impulses and a consciousness of unity which creates a “concretion of identity,” therefore objectivized culture has the structure of memory. To further elucidate the components of Cultural Memory, Assmann describes six aspects; 1) The concretion of identity, 2) its Capacity to Reconstruct, 3) Formation, 4) Organization, 5) Obligation, 6) Reflectivity. This theory provides the necessary language to articulate how memories and the memorialization of events and narratives shape cultures and individuals. This foundational theoretical work proves very useful to analyze oral history narratives of migrant women in Giving Birth. Additionally, it provides a framework for identifying the potential intersection between inherited cultural memories/identities coming into contact and relationship with those of their new countries. The concept of Cultural Memory is helpful in understanding the cultural mechanisms and perceptions at work to construct both the past and the present as participants remember and describe their personal memories and update them through various societal lenses.

Like oral history, memory studies is multidisciplinary and draws upon various fields, such as psychology, sociology, anthropology, and history. Oral historians are concerned with the subjective meaning of memories. Memory is key to identity and social existence, providing a roadmap of where we have been and where we are headed. Without memory, we are unable to construct and maintain a sense of self-identity with which to interpret our lives.

Postmemory is a powerful and very particular form of memory precisely because its connection to its object or source is mediated not through recollection but through an imaginative investment and creation. This is not to say that memory itself is unmediated, but that it is more directly connected to the past. (Hirsch, Family Frames 22)

Marianne Hirsch, identifies further crucial facets of the workings of memory in society and individuals by conceptualising and coining the term “postmemory.” Her articulation of this theory is particularly useful in analyzing individuals’ experiences and memories across multiple generations. A postmemory is bequeathed from one generation to the next, characterized by a distance from lived experience. Postmemory is an experience that is transmitted both directly and indirectly, it is distinguished from Individual Memory by its generational distance and characterized by a personal connection to the memory. Postmemory indicates a personal connection or investment and generally conveys traumatic events such as war or genocide. These are experienced and lived indirectly through the children of survivors.

Postmemories are constructed, mediated and transmitted in the retelling of events that become postmemories in the recipient heirs. Postmemories cannot be directly recalled but are recreated and inadequately re-imagined. They exist as indirect and fragmentary imaginings but nevertheless can feel as real to the inheritor as if he or she had experienced them directly. Postmemories are particularly evident with the descendants of Holocaust survivors.

False memories arise from an ideological construct that is “sustained by imagined politics of the time…Mythic imagination cannot be influenced by information.” (Portelli 26) Alessandro Portelli, an oral history expert, describes the concept of False Memory as a counter-narrative that is repeated so many times that it is not questioned or criticized so that despite facts to the contrary, it is believed and perpetuated. False memories arise from an ideological construct that is “sustained by imagined politics of the time […] Mythic imagination cannot be influenced by information” (26). This MRP does not delve into sufficient depth to determine whether or not the interviewees construct or maintain false memories. However, this concept is included because, at certain points in the interviews, there is an indication that some of the women may sanitize or clean up painful memories. There is an aversion by some to dwell on what was obviously quite a difficult period. The concept of false memory asks whether their averted gaze is conscious or unconscious. Memory is subjective, although Portelli talks about False Memory in a political context, false memories as a concept can be applied to psychological and emotional states as well and will be discussed in this framework later on.

The Photograph as a Prosthetic Memor

“Photography’s relation to loss and death is not to mediate the process of individual and collective memory but to bring the past back in the form of a ghostly revenant, emphasizing, at the same time, its immutable and irreversible pastness and irretrievability.” (Hirsch 20)

Participants in the Giving Birth project were encouraged to share images of themselves, their children, and other people, places or artifacts that they felt were relevant to their journey. Many appeared puzzled by the request to display artifacts, as they usually brought very little with them from Italy. Images and photographs hold a prominent position in oral history and memory studies because they represent the relevant life episodes in the narrative, serving as touchstones and portals into another life, interacting simultaneously with the interviewee, the live retelling of memories, as well with the researcher. Photographs act as prosthetic and interactive tools whose meaning continually evolves and relates in different ways with the present. The entire process is one of relating on multiple levels and across time for the memories to re-emerge and coalesce at the moment of the interview.

Hirsch again provides critical conceptual scaffolding from a memory studies context to grasp the role of Photographs. Photographs are “multidirectional instruments of remembrance” (Hirsch) between memory and postmemory, between remembering and forgetting. Photographs depict life and death simultaneously and are melancholic objects by nature that represent that which is no longer. They become an “index” that measures the passage of time weighing what was against what is. Although it captures a static moment, the photograph is, in a sense, still interactive as it emanates through time connecting the material presence of the subject both to death and impending doom, and to the life of the observer. This multidirectional connection applies especially to relatives who, in studying the image, seek recognition of themselves in the picture of another, for example, in photos of parents or grandparents from a bygone era. For the viewer, the photograph connects life, past-tense and death, linking and layering realities on top of one another non-linearly. It should be stressed that while the photograph documents a moment, it is not itself a memory. In fact, once taken, the photograph interacts with memories, alters it and becomes a version of memory. Therefore, Hirsch considers the photograph to be a counter-memory that actually can have the effect of replacing memories and promoting forgetting.

The photograph by its nature emphasizes “past-ness” (Hirsch 20); for example, pre-war Holocaust photographs hover somewhere between life and death, existence and non-existence. Pre-war photographs both document and generate memories of survivors as fragmentary postmemories in their children. Fragments of trauma and recollection form a narrative chain that combines testimony, photograph and postmemory.

Hirsch’s critical perspective informs the aspects of this project that deal with cultural and familial structures and unspoken rules within the Italian-Canadian community. It offers a means of analyzing and inquiring into the relationships between the interviewees and their most precious photographs and insight into how the family presented itself to the world. Role and hierarchies are indicated in poses, in what is included, or excluded. The family photograph reinforces conventions and identity, belonging and not belonging demonstrated in positioning and body language.

The context of the family album creates a relationship with distant or deceased relatives and, in the context of migration, can serve as validation or confirmation of the life decision to emigrate. Hirsch describes the viewer’s unfulfillable desire to be “seen” by the subjects portrayed in photos, to be recognized, known, related to and to bridge time and space, to transcend death and override all that separates. She points to the “Familial looking: individualization, naturalization, decontextualization, differentiation within the identification and the universalization of one hegemonic familial organization” Here Hirsch describes the “reading” of photographs, how one can detect and speculate upon nuances of relationships within the image through the presentation, posture and pose of the individuals that can denote, for instance, hierarchical relationships within the family structure and in the image they attempt to project. In attempting to decode a photograph, distant relative viewers are seeking recognition. Photographs are fragments that never reveal the whole story and are characterized by incompleteness. Reality is concealed behind the image, and all attempts to read relationships within the photograph reveal it to be a veil that frustrates and heightens the fundamental characteristic inscrutability of the medium. In a photograph, the subject’s presence is frozen in time and connected to the present but remains unknowable, unassimilable, and cannot be integrated into the present.

The Origins of the Giving Birth Project

The analyses of the interviews collected for the Giving Birth project begin with Bruna Santi. She was interviewed in 2017 for the IHP and her contribution then significantly inspired this project for which she was re-interviewed and explicitly questioned about her memories of giving birth and motherhood as a recent Italian immigrant in 1959. 7 Without dwelling too much on an interview conducted for a different project, this material is included to provide a background into the conception and realization of the current project. Bruna was interviewed with her husband, Elio, about their immigration from Italy to Guelph in the postwar period.

Elio responded to the interview questions in English sharing several heartening and comical anecdotes. In fact, his eloquence and charm gave the impression of high adventure, a thrilling and overwhelmingly positive experience. Bruna, in contrast, seated next to her husband of sixty years, painted an entirely different picture of what it was like for her to emigrate to Canada. She responded in her native tongue and softly conveyed some of the challenges she had faced as a new immigrant and mother. Bruna’s original testimony revealed a marked contrast between narratives of husband and wife and merited further study. That interview was one of the inspirations for the project, which inquires specifically into the types of experiences lived through by Bruna and her contemporaries. Becoming a parent can be a complex life transition, Bruna’s experience (like the other women interviewed for this project) was magnified by her recent departure from Italy, the loss of her networks of support, her alien surroundings and especially the language barrier. She came from a large and supportive family in Treviso and bravely chose to leave that world behind. Her testimony in 2017 highlighted how her memory of immigration, childbirth, and raising her young children bore minimal resemblance to her husband’s recollection of the same events. This revelation contributed to the research questions that have propelled this inquiry namely, why has the experience of women and mothers not been a significant focus of research until now and what can their memories and the postmemories they generated and shared with second and third generations, tell us about the immigration experience of that era. 8

Bruna and the other women participants share not only their own stories of giving birth, and early motherhood experiences, but also their reflections on how such events and circumstances contributed to a sense of cultural identity, how giving birth in Canada added to or reinforced a sense of Italian or Canadian cultural belonging. Initially, the Giving Birth project encountered some difficulty finding individuals prepared to reveal intimate details of their lives. Some declined to participate because they did not want to relive traumatic experiences, while one woman initially agreed, but withdrew at the last minute because she felt uncomfortable singing the required waiver and consent form.

Bruna agreed to be interviewed again, this time for the Giving Birth project. Her daughter Lorena Pellizzari was present. Discussions around the kitchen table as waivers were filled in immediately prior to the interview made it clear that Lorena’s perspective would add invaluable depth and context to the project, and she readily agreed to be interviewed as well. The contrast of first- and second-generation participants was immensely helpful, Lorena’s experiences shed light on what it was like to grow up in the tight-knit community of The Ward. 9

Following Bruna, Lorena was also interviewed and asked for her perspective on growing up as a second-generation Italian-Canadian child in The Ward. The content of her interview revealed layers of complexity and a new context; it also expanded Bruna’s recollection and retelling of her own experience. After this first interview, Lorena invited the Giving Birth researcher to her home for a follow-up interview two weeks later, during which she shared additional details as well as family photos. This second interview is insufficiently covered in this MRP, which – due to the scope of this work, time constraint, and COVID-19 limitations – could not locate a large enough sample of second-generation participants to create a proper study of inter-generational relationship and motherhood. 10 However, her contribution will be curated and added to the IHP online repository, where it will be presented and preserved. Lorena’s contribution, despite being a single sample, has been tremendously relevant to this study in relation to postmemory, oral history, and memory studies research into the Italian-Canadian motherhood experience.

Bruna Santi

San Martino di Lupari, Treviso 11

May 1959

"Avevamo creato quasi una famiglia tra di noi, qui in Canada."

[We had almost created a family among us, here in Canada]

Bruna Santi immigrated from San Martino di Lupari, a town in the north of Italy, in the province of Treviso, in 1959, to join her fiancé Elio who was already in Canada. He had migrated to Guelph to establish himself five years before her arrival. Over that interval, they corresponded by letter. Bruna embarked on this journey to begin a new life in a new world without any way of predicting what awaited her on the other side. They married one month after her arrival and went on to have four children.

When asked about her journey, Bruna begins this interview by describing her painful departure from the ship’s port in Genoa and saying farewell to her brother who accompanied her to the ship and stayed until after it left. It would be many years before she saw any of her immediate family again. It was a difficult step on many levels, leaving the world of familiarity for a foreign land to marry a man she did not know well by today’s standards but with whom she had corresponded by letter. The route by ship from Genoa to Halifax was an arduous two week long voyage. From Halifax, she rode an uncomfortable train that took days to arrive in Toronto. Her trepidation was not alleviated by what she observed out the windows of the dusty and uncomfortable train. Her first impressions of Canada were depressing, having just left Italy in May when all was in bloom, only to find her destination vast, desolate and barren she recalls snow-covered fields and tiny houses. “What have I done? Why did I leave Italy full of flowers?” She asked herself. 12

Lì [alla stazione del treno a Toronto] ho trovato il mio fidanzato che è venuto a prendermi con un altro amico perché lui non aveva la macchina e allora siamo arrivati a Guelph. Tutto bene, ci hanno accolto bene ma per me era tutto nuovo, mi trovavo persa.

[There [at the train station in Toronto] I found my fiancée who came to pick me up with another friend because he didn’t have a car and then we arrived in Guelph. All was well, they welcomed us well, but for me, it was all new, I felt completely lost.]

It was a difficult experience, and she longed for her mother and sisters back home, but she was content to be with her husband. She remembers the early days with her first baby as quite lonely, and when Lorena grew up, she was able to help with her younger siblings. Having her children in Canada helped Bruna feel more grounded and accepting; she expresses an acceptance of life in Canada but does not give the impression of being deeply integrated into Canadian culture beyond the Italian community. This point is strongly reinforced by Lorena, who quite plainly expresses the reality that her parents did not integrate as deeply into other communities as other Italian immigrants did. This may be because Elio and Bruna were both the only ones from their families of origin who came to Guelph or because they doubted their English language skills. Unlike other interviewees, Bruna does not seem to identify as very Canadian, but she accepts Canadian culture and life here, and Canada has become home for her.

An interesting moment occurred toward the end of the interview when Bruna was asked if she would go back and change anything about her experience.

No, sono stata contenta di come [le cose sono successe], è stato un po’ duro ma dopo tutto sono contenta di come sono andate, crescendo i miei figli con mio marito, tanto sacrificio, perché pensavo alle volte, “Se avevo tutte le sorelle…”, ho altre sei sorelle, se avevo le sorelle qui vicine potevamo aiutarci una per l’altra, però, come dicevo prima, ci si aiutava fra amiche. Se una volta dovevo andar fuori casa per qualche motivo, chiedevo a qualche cugina, venivano, oppure portavo i miei figli da loro e mi aiutavano…, avevamo creato quasi una famiglia fra noi, qui in Canada. Lo stesso io facevo per loro, e avanti.

[No, I was happy with how [things happened], it was a bit hard, but after all, I’m happy with how things went, raising my children with my husband, was a lot of sacrifices, because I thought sometimes, “If only I had all my sisters…” I have six other sisters, if I had my sisters here, we could have helped each other, but, as I said before, we helped each other among friends. If I had to go out for some reason, I asked a cousin, they came, or I took my children to them, and they helped me… we had almost created a family among us, here in Canada. I did the same for them, and so on.]

Bruna began to depict an increasingly positive picture of her life, family and community. At this point, her daughter Lorena interjected and questioned this version of events, which she remembers as being particularly hard, and more to the point, which she remembers her mother remembering (italics mine) as acutely difficult. Lorena disagreed that her mother would not go back and change certain things if that were an option. In her opinion, there were several things her mother would have changed to make life more comfortable. Lorena challenged her mother’s sanitized version of the story and directed attention to the reality of the difficulties faced and surmounted by her mother. Lorena’s definition of success and resilience are different from Bruna’s and reveal the generational divide. Pavla Miller comes to our aid in explaining this divide and its dynamics. Miller describes the mother figure in traditional Italian society as a nurturer, self-sacrificer, with a sense of “compulsory altruism” (96) and devotion to family welfare that supersedes independent pursuits. Younger, second- and especially third-generation individuals are increasingly independent and less connected in this respect, while second-generation children of immigrants must often straddle two worlds. Miller describes an emotional economy of expected repayment or recognition of the older first-generation from the second-generation. She has highlighted an undercurrent of tension between traditional expectations and modern individualism and personal freedom, as younger individuals seek careers, make time for themselves, prioritizing self-expression and a life balance despite how they may conflict with what some today consider “outdated” notions of motherhood, womanhood and compulsory sacrifice.

Miller’s ethnography illuminates generational differences and tensions expressed in the Italian diaspora 13 and the challenges faced by those seeking to bridge these divides. She highlights an area of conflict, emotional debt, between some immigrants and their children, and the evolving definitions of what it means to be a mother. In her commentary about the falling birthrates of Italians around the world, but most notably in their adoptive countries in the post-war period, Miller notes that in the pre-WWII era, families with more children back in Italy were not necessarily emotionally closer to one another. Pre- and during the WWII years, in Italy, all family members were often expected to work, pull their weight, and contribute materially to the household.

Survival in Canada depended on strong relationships between family members because of the enormous distance between their immediate family and the network of support that they left behind. Relationships potentially relied more heavily on each other within the same household. Elio and Bruna Santi did not have immediate family members to support them in their new community and felt initially quite isolated; they describe how their relationships with neighbours on their residential street became profound and lifelong. Over the years, they shared childcare, helped one another through both difficulties and successes, and referred to these enduring relationships as “like family.”

Bruna’s testimony in 2017 was candid, and yet when re-interviewed, she began, towards the end, to clean up the past and edit out some of the difficulties. Was it because her daughter was present? Did the presence of a male videographer (who understands no Italian whatsoever) impact the lens through which she viewed, recollected and shared her experiences? Bruna is a remarkably brave woman who undertook an enormously challenging journey overcoming many obstacles in her own way, which she openly discussed. She, however, also shied away from emphasizing negative or painful aspects in favour of a more neutral tone.

Additionally, Lorena gave an interview on the same day as her mother and then she followed up a couple of weeks later with a second interview, so each has given two interviews of similar material which can be compared with one another across time in a multidimensional way. In the second interview, Lorena put even more emphasis on the fact that she felt her mother had understated her experiences and challenges as a new immigrant.

Lorena grew up and internalized the memories her mother shared with her as postmemories and gave the impression of knowing them at least as well as her mother. Hirsch explains that a distance from the original events characterizes postmemories and that they are transmitted both directly, in terms of storytelling, and indirectly through actions and, in this case, presumably the fear that Bruna continued to carry around childbirth at the impending arrival of her granddaughter. An oral history standpoint considers how Bruna’s memory may have been adapted and changed in the interval 2017-2020. Was it the setting, the people present? Why has her perspective shifted? Or at least her presentation of the narrative? Such questions guide this research and continue to emerge in the analysis of the other interviews, making how one remembers the past and the internal and external influences upon its construction, one of the focal points of this MRP inquiry.

Lynn Abrams, one of the foremost oral historians upon whose foundational work oral history advanced its methods, practice and theory, always asks “why?” She asks why people remember or forget things, why they distort or make mistakes? (23) Memories are ultimately always reconstructed to align with the participant’s worldview:

Although we do still rely on our respondents to mine their memories for facts about past events and experiences, particularly in instances where the information is unavailable elsewhere, where oral history really departs from other memory sources – the memoir or autobiography for example – is in the recognition that memory is an active process. The oral history interview is an event whereby, through the relationship between the interviewer and the respondent, a memory narrative is actively created in the moment in response to a whole series of external references that are brought to bear in the interview: the interviewer’s questions, the respondent’s familiarity with media representations of the past, personal prompts and cues such as photographs and family memorabilia (23).

While Bruna’s account would not be considered “false memories” in a political context, as described in Portelli’s example, her memory may have been adapted, altered and “falsified” in a psychological and emotional sense the sanitizing of the reality, La Bella Figura (a concept this paper will address). In this way, in her daughter Lorena’s opinion, Bruna was presenting an easier and smoother narrative of cultural acclimatization while, in fact, she found it extremely challenging and lonely at the time.

Around Bruna and Elio’s home are photos of them and their family at various stages of their lives. They present a visual narrative independent of and yet supported by the interview given by Bruna. 14 Family pictures in preserving images and memory fragments are not static; they are dynamic objects that interact with the present. Images of Bruna and Elio as newlyweds at anniversaries, children’s graduation, and, above all, their nephew, tells a story of love and loss, resilience and strength, success and productivity, and a life lived in full colour.

Postmemory shares the layering of these other “posts,” and their belatedness, aligning itself with the practice of citation and mediation that characterize them, marking a particular end-of-century/turn-of-century moment of looking backward rather than ahead, and of defining the present in relation to a troubled past, rather than initiating new paradigms. Like them, it reflects an uneasy oscillation between continuity and rupture. And yet postmemory is not a movement, method, or idea; I see it, rather, as a structure of inter- and transgenerational transmission of traumatic knowledge and experience. It is a consequence of traumatic recall but (unlike posttraumatic stress disorder) at a generational remove.

(Hirsch, “Generation of Postmemory” 206)

Lorena Pellizzari

Guelph, Ontario

“Strings of Love”

Lorena sits down immediately after Bruna’s interview and gives a detailed and eloquent account of the neighbourhood where she grew up, how her parents first rented and then built the dream house in which they still reside. She explains what it was like as a child, the eldest of four children, on a street that was home to several Italian families who were primarily from the northern region of Italy. In her self-introduction, Lorena explains that when selecting her university and career options, she had hoped to pursue her love of languages at which she excelled in high school. However, her father disagreed with this choice and encouraged her in another direction. Lorena expresses some regret at following another path, instead of her heart, but concludes that it was ultimately for the best that she received a medical secretary degree that has served her well. This disagreement with her parents, mainly her father, seems to reinforce some of the descriptions of generational tensions outlined by studies of second-generation experiences of migration and integration. 15 Her father Elio was focussed on practicality and income, while Lorena wishes she could have followed her own interests:

I would have liked to have taken a different path for school, but it didn’t quite work out that way. My father was very… Well, he had his own ideas of where, at the time, where his eldest daughter should end up and how she would end up in life. So, needless to say, we had some discussions over that. And I ended up taking a medical secretarial course, for which I received a diploma. I’m very proud of that because they don’t really offer diplomas [in that area] any longer. In high school, I excelled in languages, and my teachers called the house here and spoke to my parents copious times. But because of the language barrier, I always had to intervene, and it was a difficult position for me to be in because it was like a rock and a hard place, trying to explain to them what teachers were saying, “you should continue with your education you should go on you should live up to your aspirations.” So, I thought that this would have been an easier way taking the medical route at first. I thought [of] travel and tourism and that I could use and expand my languages skills, but the medical route, I thought, was more pertinent probably. And so that’s where I went.

In this quote, she describes a situation in which she acts as an interpreter between her parents and the teachers who were trying to advocate for her educational advancement. Iacovetta reminds us how “Many immigrant children, newly conversant in English, found themselves interpreting for parents and other adults. It placed them in awkward predicaments as prepubescent girls and boys explained the intricacies of a mother’s pregnancy symptoms to a doctor or a family’s finances to a welfare worker (Iacovetta, “Remaking Their Lives” 151). Lorena provides yet another example of how second-generation immigrant children found themselves caught between two worlds, two languages, two sets of principles, and the need to navigate between them. Her memory of those circumstances is very candid and uninhibited, even with her parents present.

Moving on from there, Lorena concludes her description of her career path moves on to her experience of motherhood by briefly stating that for her, things were easier than they had been for Bruna. Lorena reiterates the struggles her mother had with stepping into the “land of the unknown” and the fears she had, which were exacerbated by her inability to communicate in English. Lorena’s postmemory of Bruna’s experience is “Not good,”

SF: Tell me your memory of the story of your mother’s birth experience.

Lorena: Not good. From what she told me, it was not good because she was by herself, because she was going into the land of the unknown again… She came here by herself, not knowing the language and only having known my dad through letters for five years.… So, [there she was] not really knowing anything, she came into the land of the unknown then with a lot of insecurities, and then to become pregnant and start a family so quickly thereafter… she [my mother] said, “Oh, no, it was very different for me, and I was in pain.” While my doctor suggested that I walk. The more you walk, the better it is for you. And so, I did. I walked. I was moving, getting up and down and walking around, up and down the corridors, and she would tell me, “Lorena sit down, Lorena go back to the bed. Oh, please don’t do that I can’t stay here anymore.” And I said, “but Mamma, I feel fine, I feel fine.” I was gathering more energy for myself. Then they come in and measure you and check your blood pressure and all that. They said everything is going along just as it should be and getting very close to the time when the baby’s going to be born. “So, would you like to walk over to the birthing room?” And I said, “yes.” Well, that was it! My mother said, “no, I cannot do this.” She watched me get up and go to the room. She went out and met with my in-laws who were waiting and told them. “She’s crazy. I don’t know what she’s doing. If it was me, I wouldn’t have done that.” And the next thing you know, the doctor came out and told them Stephanie was born. […] And I know everyone experiences it differently. I was fortunate because I did have some issues early on in the pregnancy, and I overcame them. I enjoyed my experience.

Lorena grew up absorbing Bruna’s past experiences directly and indirectly – through repeated retellings and expressed references – she related to these postmemories as if they were implicitly her own. Lorena’s recollection of what her mother had shared filled her with fear when she prepared to give birth to her own daughter Stephanie. Lorena shared a perspective that may be one of the most profound and poignant moments of this entire project. Her story is a case study on how the workings of memory, postmemory and trauma can be transmitted and healed through the conscious intentions of future generations.

During Lorena’s pregnancy, Bruna accompanied her to some of her prenatal appointments and was present in the hospital’s labour room. 16 Throughout this time, Bruna expressed fears and apprehensions based on her own negative experiences. She was uncomfortable with her daughter’s relaxed approach and, for example, her determination to follow medical advice and go for a walk between contractions and move as she laboured. Lorena was carrying a child and the intense postmemories of Bruna’s distressing birth experience and wanted to choose a different path for herself. Bruna has described giving birth in quite traumatic terms because she could not understand the nurses and doctors, she felt afraid, lost, and cut off from her network of support that she had left behind in Italy. Lorena describes that while labouring, her mother’s experience was – in a sense – superimposed upon her own. During labour and the experience of giving birth, however, rather than becoming tense and afraid, Lorena transcended both her personal and her mother’s fears, generating calm and tranquil labour and delivery and thereby “healing” her mother’s inherited generational fear and trauma.17 The greatest challenge for Bruna appears to have been due to facing the birth of her first child alone, cut off from supports, and her fear and confusion that medical personnel could not alleviate as the communication barrier prohibited her from understanding what was happening.

Her mother Bruna, sitting nearby interjects, saying that Lorena handled things far better than she had and was less afraid of saying, for example, that Bruna remembers being unable to leave her baby for a moment in the carriage, as other mothers frequently did while they worked while Lorena took a more relaxed approach.

Lorena shifts the conversation to her memories of early motherhood when her first child was an infant and to the advice and criticism, she received for doing things her way. Italian families in the Ward neighbourhood would report everything they saw back to her parents, and this may have contributed to the decision she made with her husband to live and raise their family in another neighbourhood. Although Lorena is very close with her parents and siblings, one senses that unlike Bruna, who felt alone and isolated, Lorena may have felt slightly suffocated by the intense attention she received in her family and community. 18 The dialogue returns to a phrase Lorena used in the conversation prior to her mother’s interview.

SF: Lorena, you spoke of “strings of love” connecting this neighbourhood, concerning your parents’ place in the community, and your own.

Lorena: Well, about my parents, I think, because my parents are the only two from their [immediate] family, [compared to other] families here, they needed their [Italian speaking] neighbours back then… It was a fibre that was just weaving through them to keep them all together, to keep them going day by day, giving them the support. And myself and my siblings. As we grew up, we saw the evidence of that. So, yes, it [Italian culture] is just in you, and it gives you more reason to look after one another. It speaks to the bond, and to taking it even a little bit further. That’s not to say that my siblings and I don’t- that we always get along… There are always areas where we have differences of opinion, but we do try our best to overlook those. And when we get together, we try and enjoy each other’s company. So even to this day, just last weekend, we got together, and we reminisced, we don’t [always] include our parents… So, I think it’s all part of the fabric. It’s all woven in together. I think it’s [there] from when you were young, [through] every stage of your life, and now into adulthood. It’s proven to be an essential part of our lives.

Lorena describes her family values of family connections, volunteerism, and active engagement with the Italian community and the broader community. Values that she’s instilled in her children and hopes that they will carry on in their future families. However, she notes, some cultural values she hopes will be transmitted and others “modernized or tweaked a bit.” When pressed, she simply says that it is difficult to choose, and she can’t pick which respects to leave out. Lorena maintains her family’s connections to aunts and other relatives in Italy. She veers into a story about a vacation she took to meet her two grandmothers before going to university. Lorena yearned for a deeper connection with the relatives that had remained in Italy. Over the years, she has fostered that connection for herself and her children who have developed relationships with the cousins in Italy, with whom they communicate frequently.

Several times Lorena uses the word “connecting,” and that seems to be the best way she approaches family and culture, connecting communities, connecting family members and connecting generations through strings of love that are woven into a cohesive tapestry that encircles and holds her family and community together. She concludes the interview by expanding on the question of where her cultural home is. Lorena’s lyrical response is included here:

My cultural home is in Italy. That’s not to say that I’m not proud of being Canadian – It’s just because that’s where I feel everything started. That’s where [my parents] came from, so it started there. Canada offers us so much, and when we go back, we see the differences. We’re proud to be Canadian and to have what we have here. We talk to our relatives and find out how they live life there, and it’s completely different! There are aspects that you want and parts of what we have here… And we’d like to combine it all if only we would be that fortunate! There is beauty in Canada… and there is beauty and history in Italy… when we go to Italy, there’s something about it, you just feel like you’re at home… Yeah, because that’s where it started, I think it’s the fabric that’s being woven and continues on. Who knows where we’re all gonna end up next…?

While similar testimony and a larger sample of second-generation immigrants would further elaborate on this topic of inquiry, Lorena’s contribution unites many of the streams of theory and methodology that have informed this paper and regretfully cannot be adequately pursued at this time.

Iole Cazzola

Torreselle, Padua

1961

"Love brought me to Canada"

Iole Cazzola, although new to oral history projects in Guelph, graciously agreed to participate in the Giving Birth project in support of the preservation of women immigrants’ experiences. Having worked for decades at the Guelph’s Vice-Consuls General office, she has numerous community connections. The principal investigator of the Giving Birth project had previously paid her a brief visit to discuss the aims of the project and to ask Iole for assistance with the procurement of other participants. Iole invited her sister-in-law Lidia and her friend Amabile to be interviewed with her on the same day. All three women were interviewed at the same time and asked similar questions to those posed to Bruna (as per the interview template). Upon arrival, Iole’s husband Olivo was genial and welcoming, demonstrating many photos and artifacts for the researcher and making all feel welcome. Olivo gave the impression of having some good stories to share and would be an excellent candidate for a future interview for the IHP in Guelph.

Throughout the interview, Iole appeared slightly uncomfortable with the personal questions and afterwards said that the process had been harder than she thought. The questions were simple, and the probing as gentle as possible. As the interview progressed, she gradually revealed more about her upbringing in Italy and the immense difficulties she had encountered as a very young child. This description of her conversation will attempt to follow the structure of her revelations to maintain the emphasis placed by Iole on specific aspects of her life.

Iole immigrated from Italy in 1961 and has been an active member of the community working and volunteering in Guelph with Italians and non-Italians for several decades; she held a position as assistant to the Vice-Consul General of Italy since the early 1980s and is now retired. (“End of Era”) She has lived in the same house in the Ward for 57 years and has raised three children with her husband, Olivo.

Iole is an elegant, tidy woman and speaks softly in sophisticated English. She opens the interview by saying that love brought her to Canada to marry Olivo who had come to Guelph seven years prior. They were raised in the same northern town of Italy, Torresselle, and were well known to one another. Like Bruna and Elio, they corresponded for years by letter before she made the journey to Canada to marry her fiancé. Instead of traveling by ship from Italy, like so many others, Iole flew to Toronto and describs being filled with excitement and happy anticipation of learning the customs and language of Canada. Unlike most other participants for the Giving Birth project, Iole’s first impressions of Canada were positive: “It was a good impression. Of course, everything was different, and everything was new, but I’m the type of person to accept different things. So… except at first, it was very hard not knowing the language…”

However, rather than beginning a new life in Canada, Iole and Olivo always planned to return to Italy after a few years and she planned to use her knowledge of English there, presumably to teach. Once she established herself and had her children, the idea of returning to Italy became increasingly remote until she and Olivo decided to remain and build their lives in Guelph.

At the time of her departure from Italy, Iole, an expert seamstress and artisan, packed her sewing materials and several embroidery pieces, which she still has. 19 Iole has shared her passion for handwork and embroidery with her granddaughter who has an interest in her grandmother’s work. In this way, Iole has maintained Italian cultural handwork traditions and transmitted them to future generations.

Iole describes her immigration experience and pregnancy in Guelph as not particularly difficult or traumatic because she had a doctor who spoke Italian. However, when giving birth at the hospital that doctor wasn’t present, and communication was a challenge. “One thing that helped on that was having a doctor speaking Italian, so through the pregnancy, it was fairly easy for me. But then at the hospital, it was totally different because there was nobody that spoke Italian. So, it was a little hard.” She briefly alludes to difficulty with the birth of her first child but declines to go into further detail. The Italian speaking doctor came to the hospital to congratulate her afterwards, and this gesture meant a lot at the time, given the difficulty she experienced.

As a new mother, Iole found a strong support system in the local Italian community and with her sister-in-law Lidia who had immigrated a few years earlier: “It was pretty good, we stayed mostly within our Italian community, you know, and… so it was pretty good. We had a sister-in-law that had been here already for a few years. Oliver’s brother and his wife, and she gave me some points somehow.”

One year later, she and Olivo welcomed their second child, so they had two small children close in age. Iole says that having children made her feel more Canadian and more settled here. She and Olivo shared photographs of their early years in Guelph. One in particular of her small children playing in the snow resonated as a particularly Italian-Canadian image.

A year after I had another child and so when the second one was six months old, and the other was a year and a half, I went to night school to learn English because [merely learning] a word here and there was not the right way for me to learn. So, I went to night school, and that gave me the basis of a proper way to express myself… Olivo would stay home with the two babies.