Research by Sophia De Goey

Table of Contents

Introduction

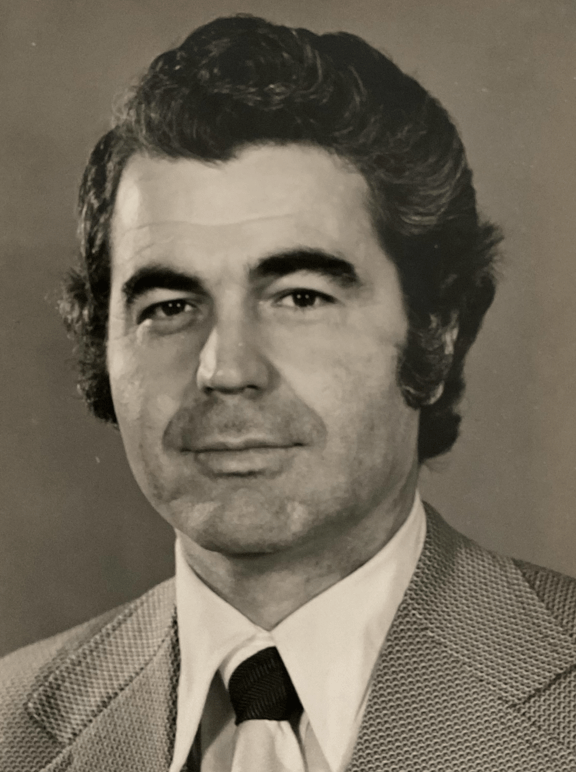

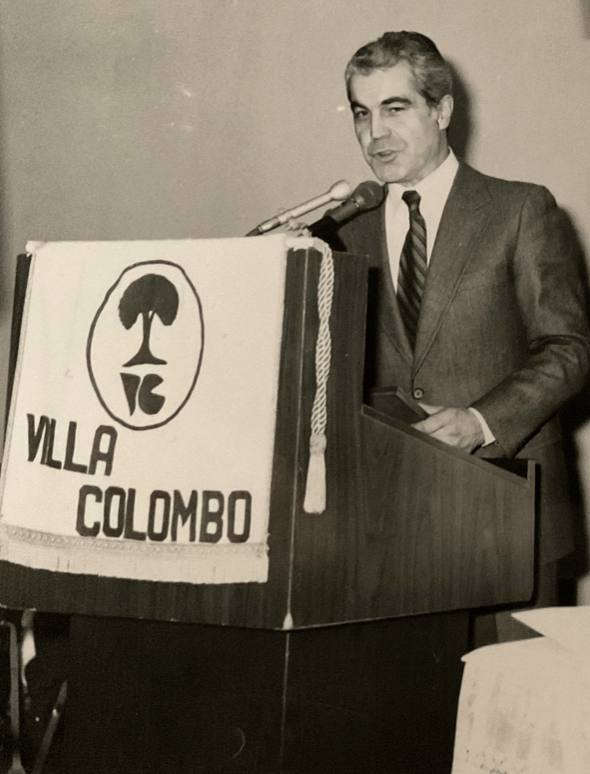

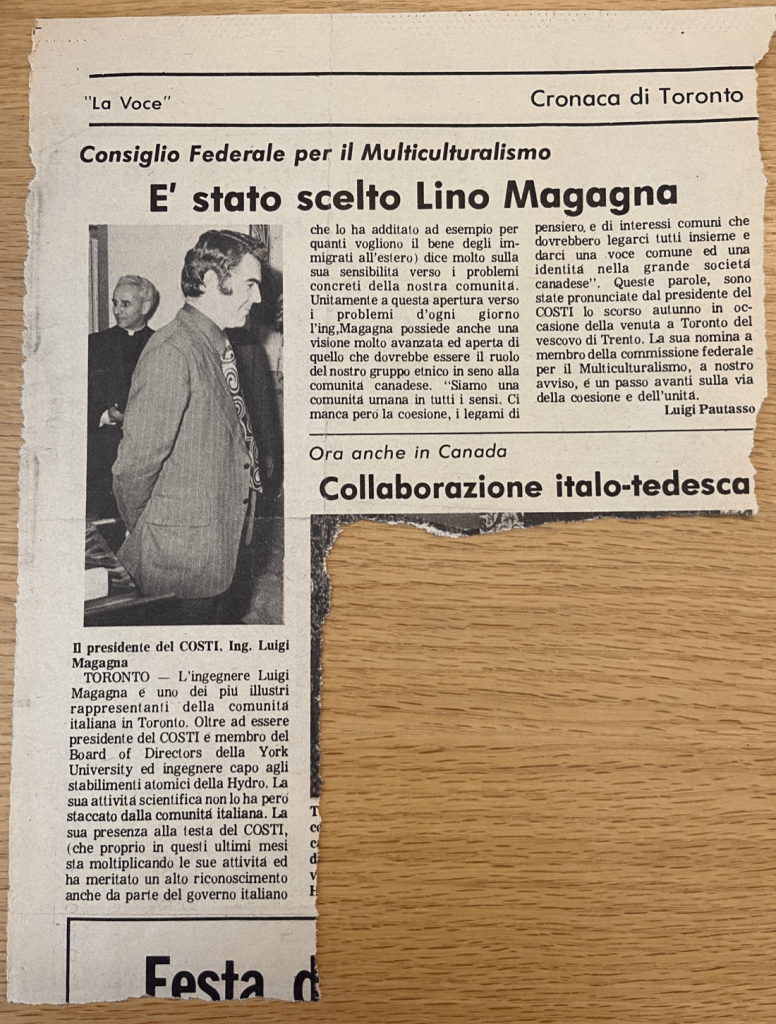

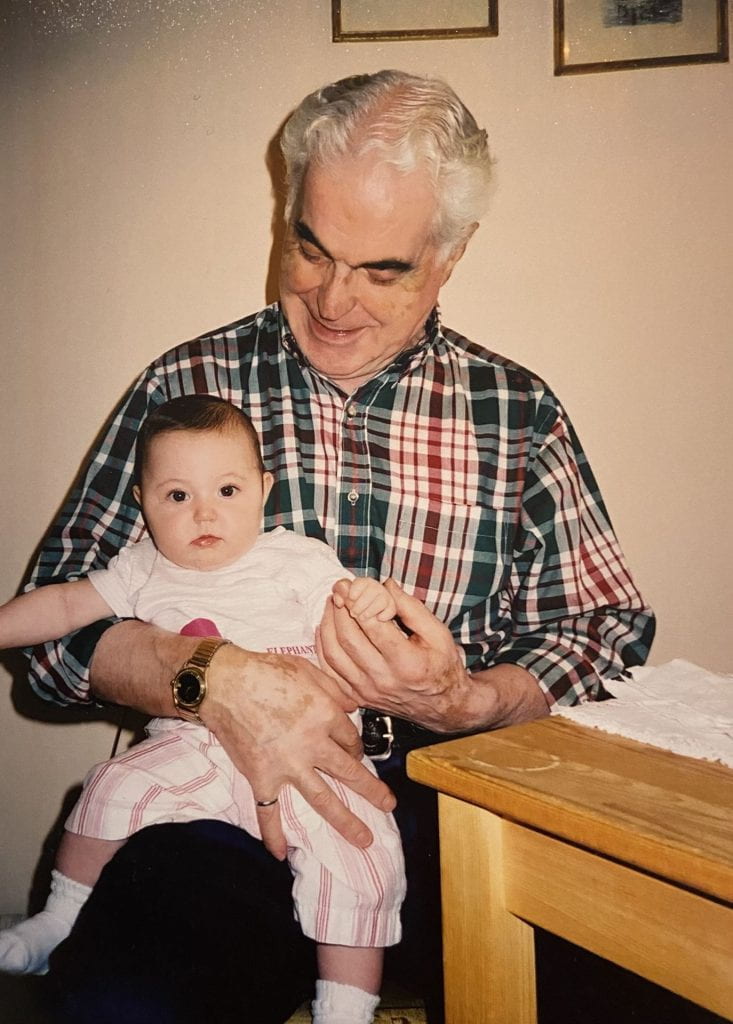

My grandfather, Lino Magagna (C.M., E.MBA, Ph.D., P.Eng.), emigrated from Italy in 1952. Despite knowing no English upon his arrival, he went on to be not only an esteemed Academic and Businessman, but also the President of COSTI, a highly influential Italian-Canadian nonprofit, from 1971-1979, after serving on the Board of Directors since 1968.

This is his journey from Italian farmhand to Member of the Order of Canada. Because he is no longer with us, I have to interviewed three people who have some of the best insight into his life: his brother, Sandro Magagna, his ex-wife, Rosemary MacLean, and his close friend, Robbie Shaw.

All photos are derived from my personal collection and copies of COSTI documents from their website and from the Archives of Ontario. My extended thanks to all those above, whose contributions made this project possible, and also to my mother and uncle, Marina and Mark Magagna, for their additional research.

Beginning in Italy

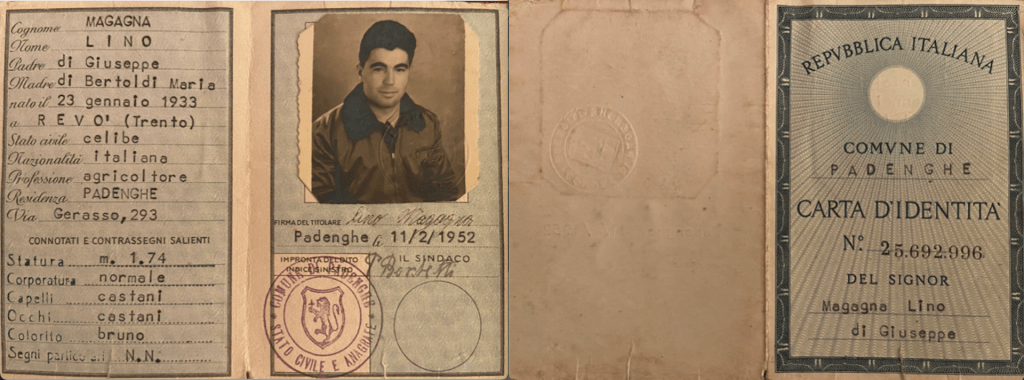

Lino Magagna was born on January 23, 1933, in Revò, Trentino, Italy. He was the second of four sons to parents Giuseppe Magagna and Meri Bertoldi. He grew up in the Northern mountains of Italy, and was six years old when World War II began.

During the war, his father was taken prisoner under allegations of Communist sympathies. Even as a child, Lino was staunchly opposed to the fascists. His brother, Sandro, recalls an incident in 1945:

“I remember a day when the soldiers were going by, they were losing the war, and they passed by our village. My father and Lino—I wouldn’t say stole them, but almost—they stole two horses from the Germans. But somebody told them that it was very dangerous, so they gave them back. At that time, it didn’t take much to get shot.”

— Sandro Magagna

Despite his opposition, Lino was required to participate in the Gioventù Italiana del Littorio, a fascist youth organization, with all the other boys his age.

Once the war had ended, Lino took up work as a farmhand to a few local families. He was paid in food and access to their home libraries, from which he gained a love of reading. In 1950, the Magagnas moved from Trentino to Padenghe sul Garda in search of better farmland. Lino didn’t stay in Padenghe very long, however. His maternal aunt, Zia Annie, had been living in Vancouver, British Columbia, for a few years and was awarded the ability to sponsor a relative to move to Canada. Lino and his brothers had already been discussing immigration to America, and at the young age of nineteen, Lino decided that this was the best step for him.

Immigration

On Easter morning in 1952, Lino was the first of his brothers to leave home. The tale of his immigration, however, was always left a mystery. He did not like to reminisce about the journey or divulge many stories, and so we know very little. What we do know is this: he took a train from Padenghe to Rome, where his boat, Argentina, was docked. From there, Argentina sailed to Halifax, where he disembarked at Pier 21, which was at the time Canada’s central ocean immigration terminal. Upon arriving in Canada, he spoke no English, and brought only a suitcase filled with only a change of clothes. From Halifax, he took an antiquated passenger train, outfitted only with wooden benches for seats, and began his journey to Vancouver. As soon as he arrived to stay with his Zia Annie, it is said that he slept for a full week, only waking for meals, to make up for the exhausting voyage across the Atlantic and the North American continent.

Beginning Again in Canada

Lino’s first job in Canada was as a woodcutter of the Trans-Canada Highway up the Fraser Canyon, which he’d gotten through recommendation from his Zia Annie, whose husband had been in the business. With very little English and an incomplete education, he was limited to manual labour professions. The job was only for the summer, and so once the autumn came around, he began a new one at the Lionsgate Bridge. He was to build steel cable fishnets to drop into the Vancouver Harbour to prevent any postwar submarines from gaining access to Canada.

While working there, Lino learned that there were higher-paying opportunities for men who had acquired a mechanic’s certification at the British Columbia Institute of Technology, and so he set his sights on accomplishing that. Unfortunately, it required fluency in English and a high school equivalency diploma, neither of which he had. He was not deterred. He enrolled in English classes, but found the group format to be too limiting, and so asked the teacher for private lessons. She agreed to teach him, if he would come to her house twice a week. She lived in Point Grey, on the West end of Vancouver, whereas Lino was boarding on the east side, but he was again not deterred. He committed to the lessons and took the streetcar twice a week for an hour each way. Within the year, his English was so impressive that native speakers could not even detect an accent in his words.

With his newfound fluency, Lino flew through his high school night classes, aided by his passion for reading and mathematics. He graduated top of his class in 1954. With the obstacles out of his way, he immediately enrolled in the Institute of Technology, and graduated top of his class again in 1955.

University

Lino set his eyes on university, and was accepted into the University of British Columbia’s Engineering program for the 1956-57 school year. It was in his first year French class that he met his future wife, Rosemary MacLean, due to an alphabetical seating arrangement. Upon graduating, Lino received the Ford Foundation Fellowship grant for his high marks, and was able to pursue a Master’s and Doctorate degree with the money. He and Rosemary married and relocated to Toronto in 1960, where Lino completed his Doctorate thesis, On a system described by a tridiagonal matrix and its control by parameter variation, in 1965. While writing his thesis, he took on a job at Ontario Hydro, supervising the development of Ontario Nuclear Power Stations’ computer controls.

Involvement with COSTI

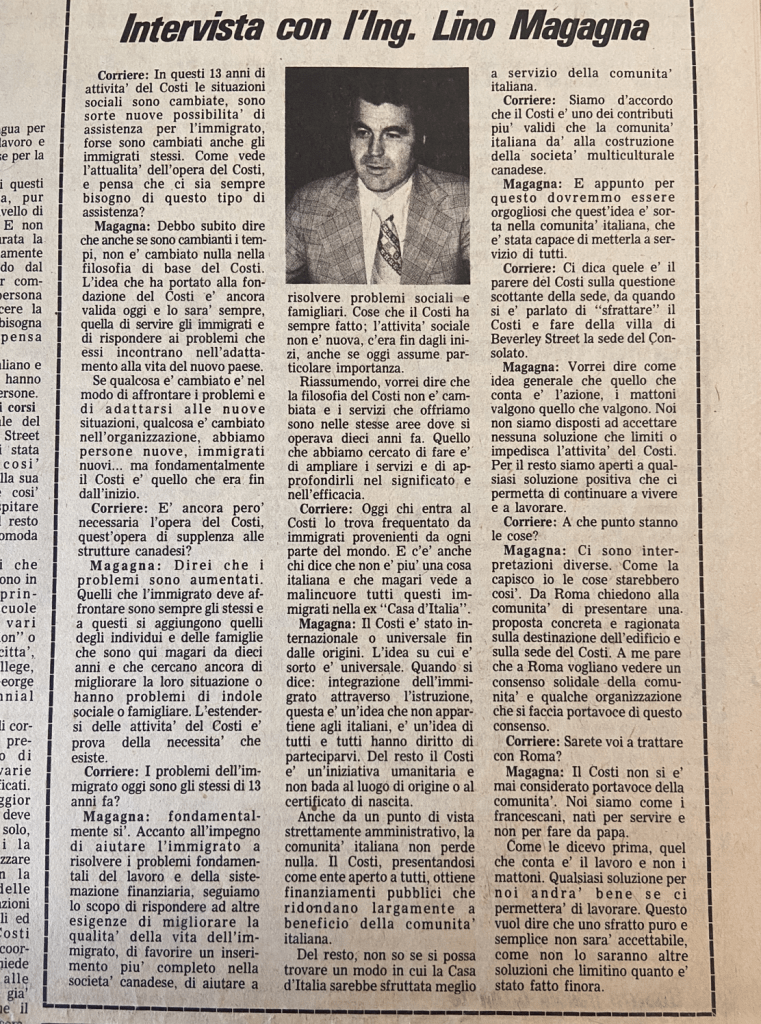

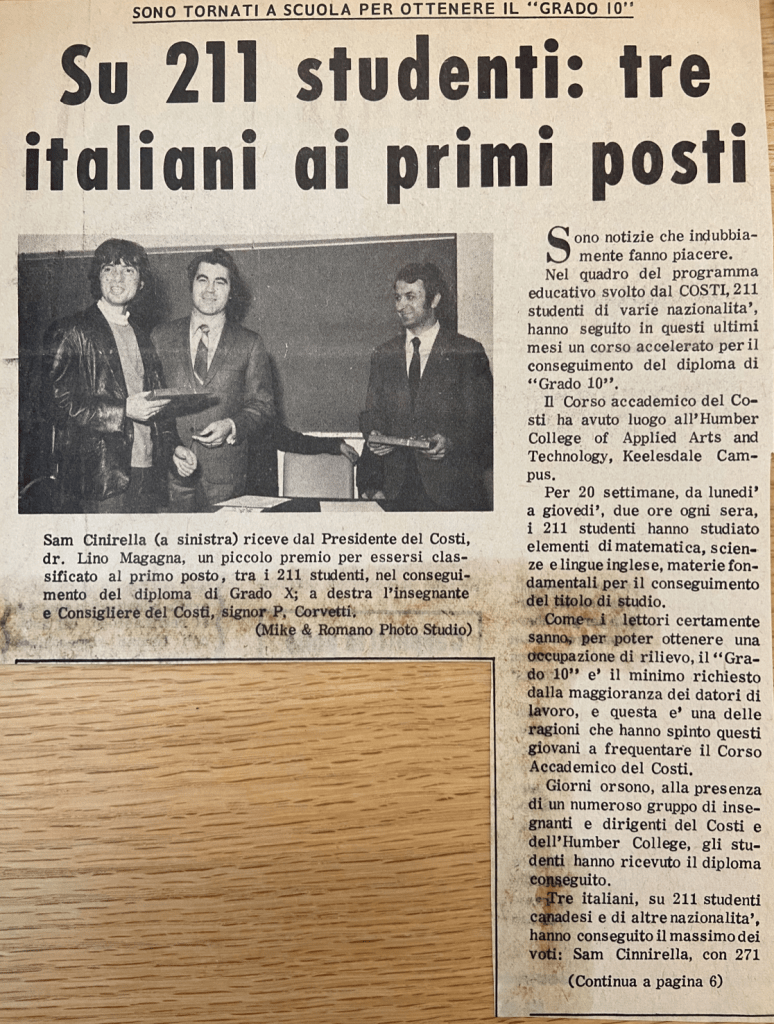

One day, on a lunch break walk down Beverley St. in 1965, Lino came across a couple of Italian men renovating a large old house, so he struck up a conversation. These two men were the Hon. Charles Caccia and Rev. Joseph Carraro, and they were in the process of turning the defunct Italian Consulate into the headquarters for COSTI (Centro Organizzativo Scuole Tecniche Italiane), a new non-profit with goals of helping new Italian immigrants to learn English and trades to ensure success in Canada. Immediately interested, Lino stayed in contact with them and was appointed secretary that same year. By 1971, he took on the role as President. COSTI credits him as an incredibly influential leader, having been “the driving force that gave the agency a strong administrative foundation” as well as setting up the IIAS (Italian Immigrant Aid Society) merger before his retirement from the role in 1979. During these years, he also served on the Board of Directors for York University.

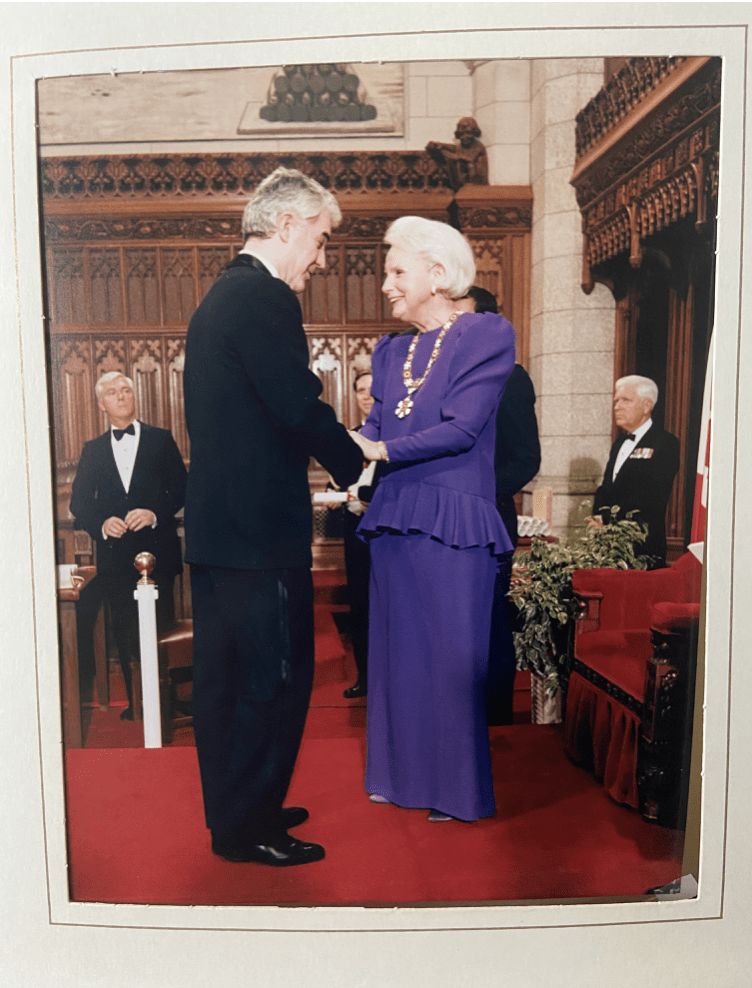

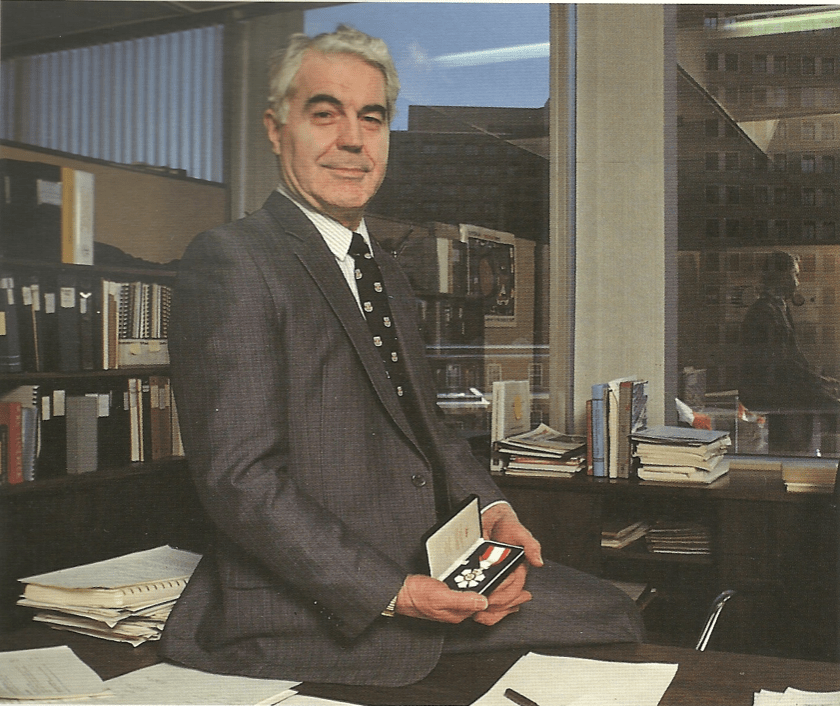

Member of The Order of Canada

For his extensive contributions to the Italian-Canadian community through COSTI, as well as the National Congress for Italian Canadians, which he founded in 1974, Lino Magagna was awarded the Member of the Order of Canada medal on May 6, 1988. He also received medals for the Golden and Diamond Jubilees. In 1989, Lino was featured on four pages of Kenneth Bagnell’s book, Canadese: A Portrait of the Italian Canadians.

“[Lino Magagna] would become one of the most influential and respected Italian-Canadians of the country.”

— Kenneth Bagnell

“The urge to stereotype any group seems to come from an urge to introduce order of some fashion, to categorize. It is easier to deal with people that way–not as individuals but as a group. Yet Italy is an amalgam of such different groups of peoples, that the stereotype doesn’t make any sense. The people I come from in the north are closer in history to the Austrians over the hill than to the people of the south around Florence. And the people of Florence are different again than the Neapolitans. So stereotyping is a fact only because people stereotype. Still, it is disappearing, there is much less than when I came to Canada in the fifties.”

— Lino Magagna, as quoted in Canadese

Legacy

Lino Magagna enjoyed a long retirement until his passing from cancer in 2017, at the age of 84. Because he himself could not contribute to this project, there are plenty of details about his immigration that are missing. This is not due to lack of trying. He was notoriously private about his life before Canada, and especially about his journey on the boat and train, and did not disclose these details to anyone. To him, Canada was his only home, and his life only truly began upon arriving in Vancouver in 1952. What we do know, however, is the remarkable life he built for himself from an empty suitcase and a passion for learning, and the ways in which he was able to provide for so many other Italian-Canadians throughout his life.

Bibliography

Archives of Ontario. F2117-10. COSTI newsletters and media sources. Newspaper Clippings.

Bagnell, Kenneth. Canadese: A Portrait of the Italian Canadians. Macmillan of Canada, 1989.

MacLean, Rosemary. Personal Interview. 12 August, 2023.

Magagna, Sandro. Personal Interview. 13 November 2022.

Shaw, Robbie. Personal Interview. 25 October 2022.

How to cite this research:

De Goey, Sophia “Lino Magagna: The Canadian Dream, and his Dedication to a Better World.” In Italian Communities in Canada: Heritage, Cultural and Ethnographic Studies: Legends, suprv. Teresa Russo. University of Guelph: December 2023, Guelph (https://www.italianheritage.ca/2023/12/02/lino-magagna-the-canadian-dream-and-his-dedication-to-a-better-world/). Italian-Canadian Narratives Showcase (ICNS), Sandra Parmegiani and Gurpreet Kaur.